Design history is commonly defined by European, colonial, capitalist, and patriarchal values. In this short essay, I will share six orientalist posters that served as advertisements promoting a fantasized Morocco in the 19th century yet are overlooked in the history of graphic design. Advertising and publications shape everyday life culture, values, beliefs, and lifestyles. In this context, oppressive and colonial narratives have been disseminated. That is, orientalist enthusiasts of all things oriental employed colonial and stereotypical associations on Morocco to design posters.

The first posters can be traced back to the early 1890s when the P.L.M. network (Paris, Lyon, Mediterranean) expanded to Algeria and Tunisia, a few years before the protectorate lasted from 1912 until 1956. Because of the development of transportation and travel companies promoting tourism, the genre experienced a massive boom. These posters were first full of colonial exoticism. Later, the colonial perspective became more subtle, with the commissioned artists focusing on the landscape, the nuances of the color palette, and the light as persuasive means for Europeans to visit Morocco. In the second half of the 20th century, printed media started to replace paintings and illustrations with typographic compositions to attract tourists, which certainly coincides with the flourishing modernist movement and, on the surface, the dismantling of an exoticized representation of Moroccans.

chez M

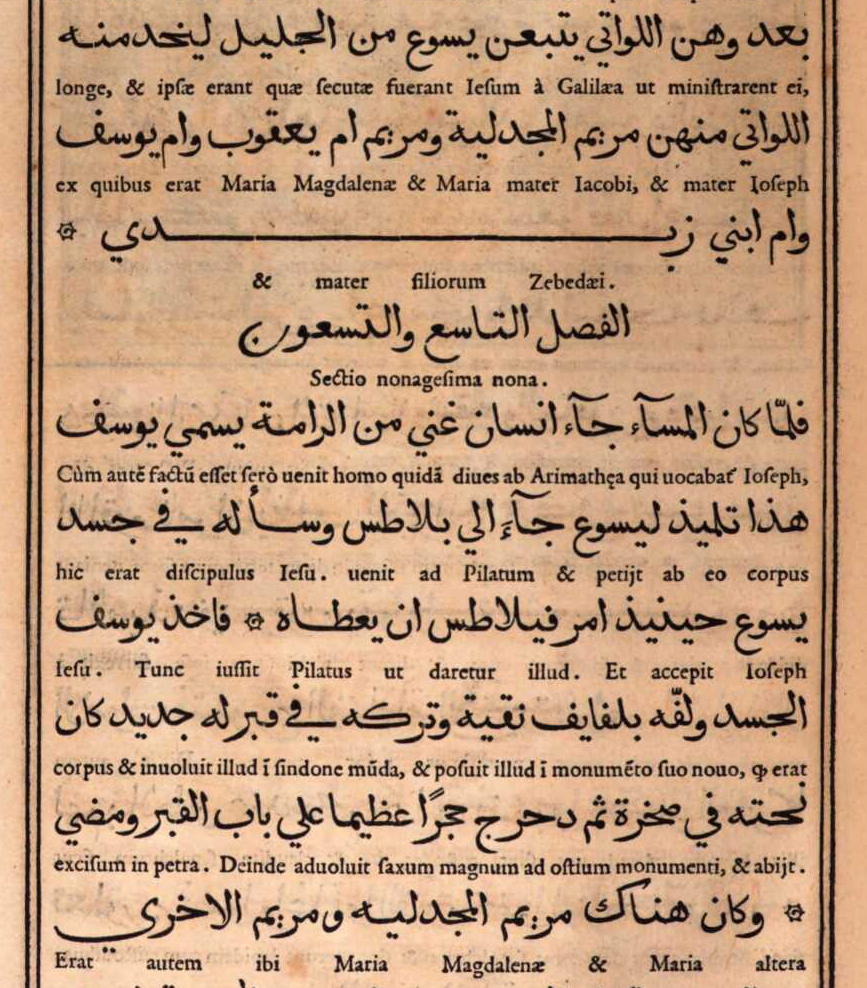

Translation of messages:

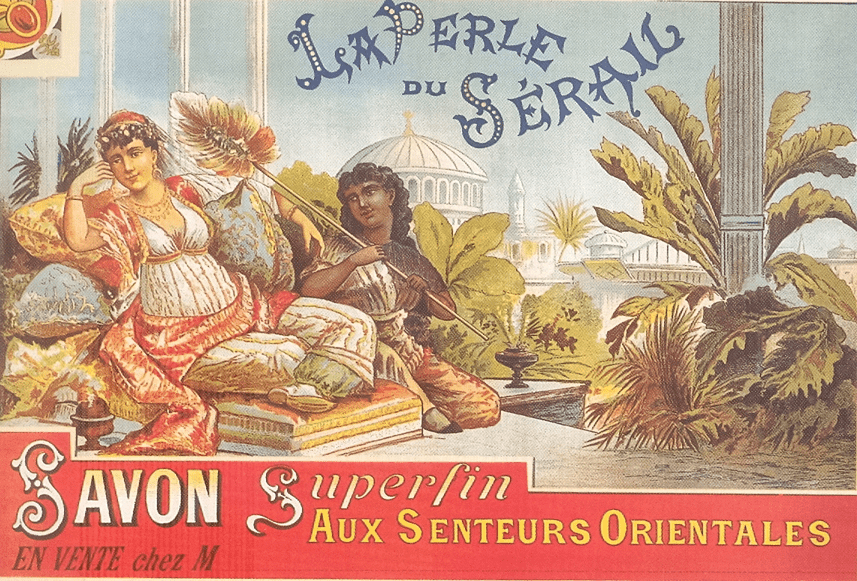

The Pearl of Harems, superfine soap with an oriental scent, Sold at M

La Perle du Sérail’s soap advertising for “M” follows a Victorian aesthetic mixing several typographic treatments, colors, and textures. Its tone is colonial, reinforcing the imaginary of racist and sexist exoticism. That is, this advertisement is used to portray a sense of luxury associated with an “oriental scent.” In addition, it is promoting cleanliness by depicting white skin, a common marketing argument following the standard of beauty of that time. Indeed, we see a Moroccan woman with white skin wearing traditional clothing, laying passively on several pillows next to her enslaved Black woman, who is using a leaf to keep her cool. Both look content with their situation. The palace and vegetation in the background further add to the oriental lavish stereotype.

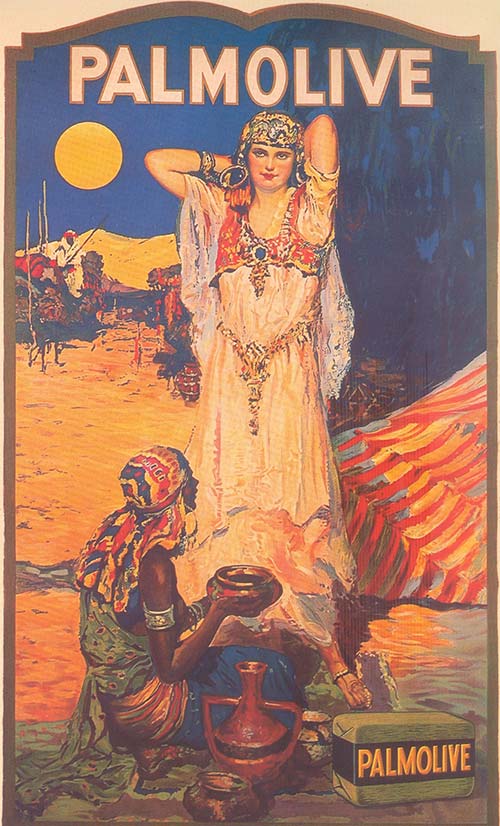

Translation of messages:

The Pearl of Harems, superfine soap with an oriental scent, Sold at M

Similarly, this early 20th-century poster promotes the whitening benefits of the Palmolive soap, which first appeared in 1898. The sand, the tent, and the man on a horse in the background refer to the Moroccan Sahara. In the foreground, we have a sexualized amazigh woman with white skin adopting a sensual posture. Next to her is her enslaved seated Black woman holding a bucket of water for her. This poster is another racist, sexist and stereotypical depiction of Moroccan life.

Translation of messages:

The laundromat of Algeciras only uses La Coquille soap, Ogé, 1906

This advertisement promotes a laundromat that uses the popular soap, Savon La Coquille, only on the surface. The poster shows Marianne, Guillaume II, Edward VII, and Alphonse XIII scrubbing, in a small bucket, a helpless and struggling Sultan of Morocco, Moulay Abdelaziz, under the watch of Uncle Sam. The Sultan carries a sign around his neck spelling Maroc (Morocco) in all caps. Under his oversized helmet, Victor Emmanuel II blindly holds a bar of soap. Finally, Nicholas II is portrayed as a child, wearing a bib and slurping soap.

In this visual, Ogé illustrates the main imperialist European powers whitewashing Morocco, playing with the same racist belief that darker skin is dirty. The Sultan is further portrayed as a bestial character, implying the inferiority of his existence simply for being a brown man. This poster was published after the Treaty of Algeciras was signed on April 7, 1906, which forced Morocco into the Franco-Spanish protectorate that followed. Its virulent tone is undeniable.

Translation of messages:

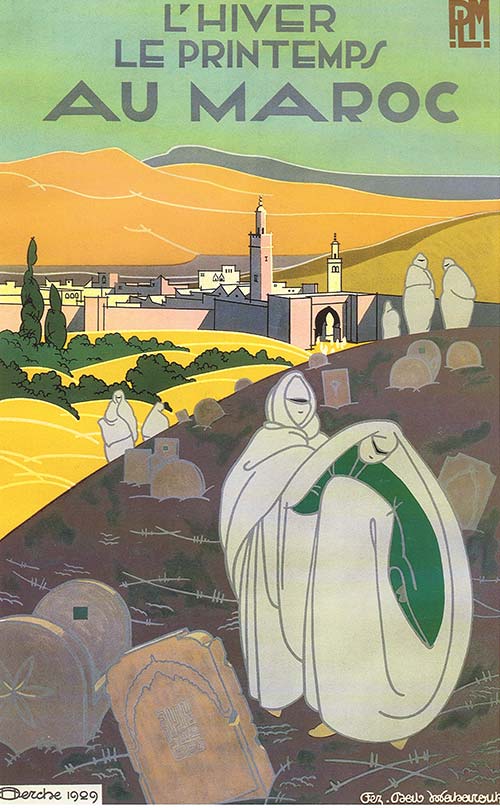

Winter, Spring, in Morocco, Derche,1929

In this 1929 poster designed Jules Henri Derche for PLM, we can see eight women wearing their white haik in a cemetery. Because women are not allowed to attend funerals in Morocco, we can assume that they are simply visiting loved ones who passed away. In the foreground, we see the Shahada—the Muslim declaration of faith—written on a tombstone using the square Kufic, a variation of the Kufic script that was designed for architectural purposes. In the background, the old city of Fez and the Mabrouk Bab (door) are lit with pastel colors. The art deco Latin letterforms translate to: “winter, spring, in Morocco.”

It is certainly unconventional to advertise a city by putting a cemetery in the foreground. And in some regards, this advertisement is moving further away from the blatantly racist language that the orientalist posters displayed in the past by centering around an everyday life scene. However, I would still argue that the visual is objectifying Moroccan women in a way that imposes the white male gaze.

Translation of messages:

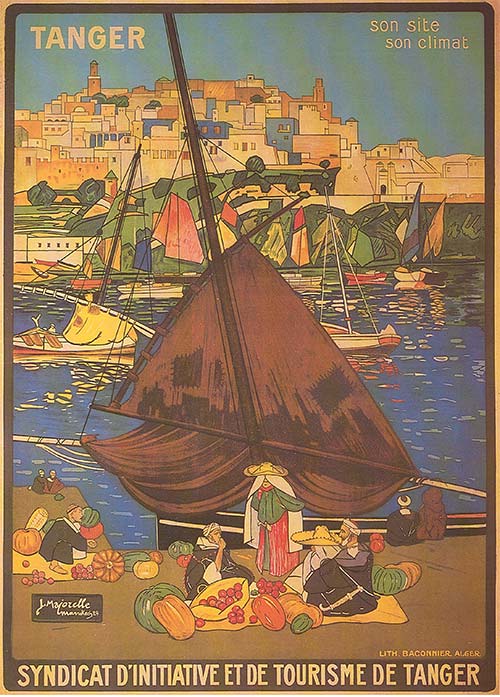

Tangier, its landscape, its climate, Jacques Majorelle, 1924

Printed by Baconnier in Alger, this lithograph was designed by Jacques Majorelle. He produced multiple posters for Morocco, reinterpreting architecture, urbanism, and ethnographic characteristics to promote tourism. With a romantic color palette, Jbalas—amazigh merchants—recognizable from their iconic outfits, are painted selling produce during sunrise. The poster also depicts boats on the Mediterranean Sea, referring to the port of Tangier, in front of the old Medina (old city). According to Abdelaziz Ghozzi, this poster for the Initiative and Tourism Syndicate of Tangier was very successful and was printed during the inauguration of the first berth in its port in 1933. This is not an uncommon scene in Tangier even until today and in many ways is the furthest away from the previous colonial stereotypes, yet does not remove exoticism from its visual language.

Translation of messages (Top to bottom):

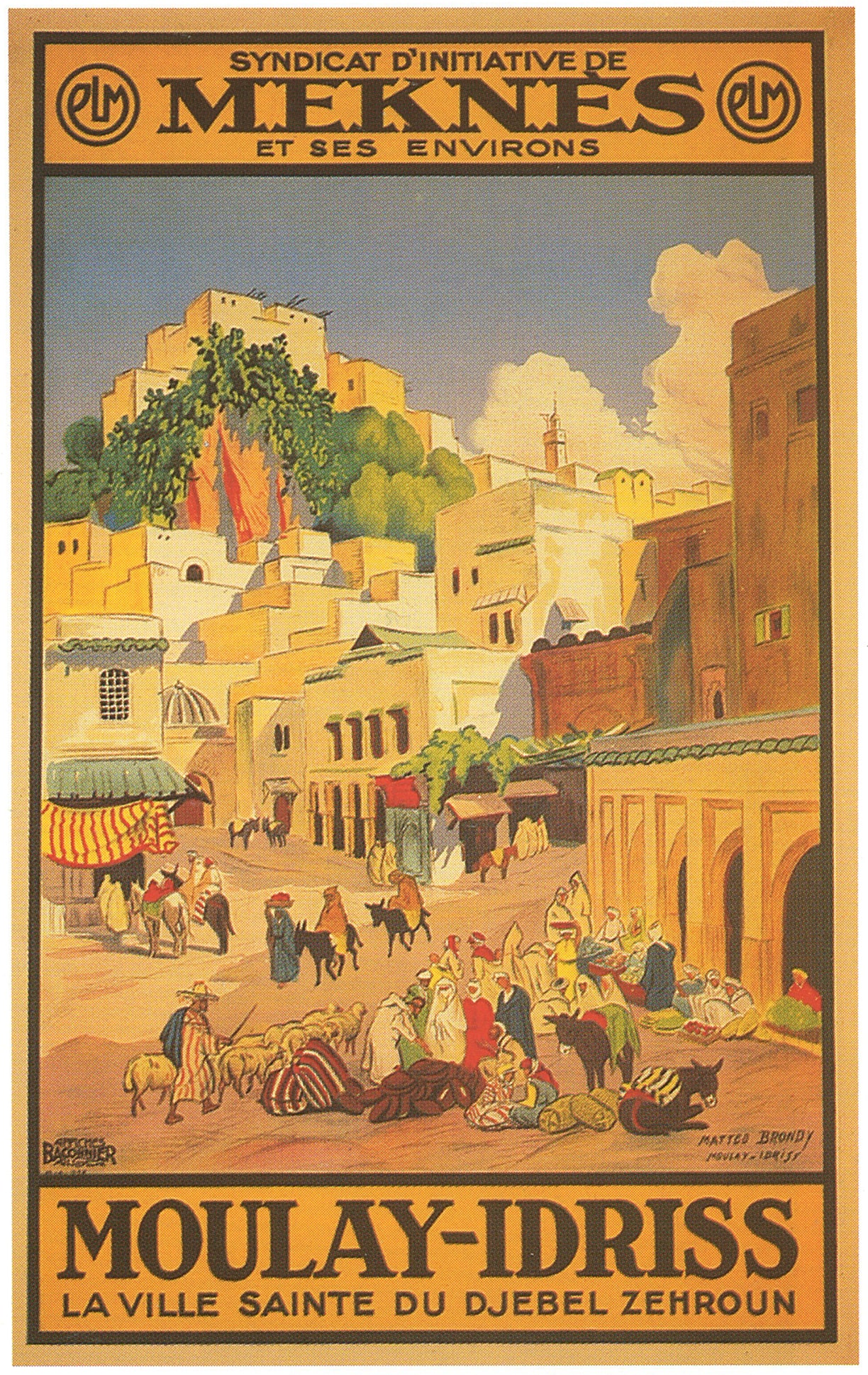

The Initiative Syndicate of Meknes and its Region, Moulay-Idriss Zerhoun, the sacred city of Djebel Zerhoun, Matteo Brondy, 1930

Matteo Brondy was a painter, illustrator, and veterinarian who lived in Meknes. He was also the president of the Initiative Syndicate of Meknes and, as a result, created multiple posters to promote the region around the city of Meknes. In this particular lithograph printed by Baconnier in Alger, Moulay-Idriss Zerhoun is advertised as a sacred city. Idris 1 Ibn Abdellah, the founder of the Idrisi dynasty, being the first Islamic dynasty in Morocco, is buried there. Every summer, Moulay-Idriss Zerhoun attracts thousands of pilgrims in search of the benediction of Idris 1 because he is a descendent of the Prophet Muhammad. Instead of illustrating this unique event, Brondy painted an everyday life scene, as Jacques Majorelle did with Tangier, where we see a few merchants, some buyers, a shepherd, and a couple of donkeys. The light is similar to Majorelle’s as it could be either sunrise or sunset. Once again, life in Meknes is romanticized and idealized in this advertisement which makes it another object of colonial perspective.

Healing starts by acknowledging faults and offering repair. The fact that design history overlooks orientalist posters on Morocco does not offer any kind of repair. Hopefully, writing about this topic to make oppressive depictions—whether deliberate or subtle—visible can be a call for repair.

References

- Arama, Maurice. 1991. Itinéraires Marocains: Regards de Peintres. Jaguar.

- ATLASINFO. 2018. “La ville sainte de Moulay Driss Zerhoun, haut-lieu de pèlerinage et de spiritualité.” Atlasinfo (blog). August 21, 2018. https://atlasinfo.fr/la-ville-sainte-de-moulay-driss-zerhoun-haut-lieu-de-pelerinage-et-de-spiritualite_a93464.html.

- Ghozzi, Abdelaziz. 1997. The Orientalist Poster. Malika Editions. Abderrahman Slaoui.

- “Idrīs I | King of Northern Morocco.” n.d. Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed September 23, 2021. https://www.britamknnica.com/biography/Idris-I-king-of-northern-Morocco

- “Les Orientalistes.” n.d. Musée Abderrahman Slaoui. Accessed September 23, 2021. https://www.musee-as.ma/fr/collection-on-display/collections-permanentes/affiches-orientalistes/