Month: November 2020

Under the Surface of Style

Arabic Film Titles Archive

Researchers:

The Arab Film Archive is an initiative that aims at collecting and digitizing classical Arab films in order to make them accessible for educational and research purposes. It is a project that provides a temporary answer to the ongoing monopoly of hundreds of Arab movies that were sold under complete exclusive rights to private TV networks back in the ‘90s and early 2000s without any consideration of the need to provide them on an institutional right basis for education and/ or individual research. The Arab Film Archive is founded by Ahmad Ameen, a film researcher and writer currently based in Amman.

Arabic Design Archive (ADA)

The Arabic Design Archive is a research initiative that is aiming to preserve, document, and disseminate historical material about Arabic design. The project’s goal is to make these materials available for scholars, students, and practitioners to facilitate research and publishing about the history of Arabic design. The project has a collection of book covers, stamps, posters, lobby cards, flyers, film titles, cassettes, VHS tapes, and other materials.

Researchers:

Moe Elhossieny, Nourhan, Elbanna, Omaima Dijani, Yaman To’ma, Karim Fouad, Sophia Alami

Press:

VICE ARABIA

SCENE ARABIA

CAIRO SCENE

ITS NICE THAT

AL AHRAM

Al FANAR

Print Mag

Frizzifrizzi Mag

Creative Review

Egyptian Streets

Arabic Commercials Collection

Arabic commercial archive is an extension of the Arabic cover design archive project. This project unearth commercial design from books, magazines, and publications from the 30s to mid-90s.

By:

Trucks: A Moving Canvas

Buying a truck is expensive in Egypt, not something many can afford, and therefore the object of great envy. The truck represents a means, no matter how meagre, of economic advancement. While in many cases drivers are employed by the owner of the truck, regardless of ownership and financial liability, driving a truck in Egypt is a dangerous and risky business, both economically and physically. Egyptian roads and motorways are among the most dangerous in the world, and life and limb are at stake on every trip, along with the investment of the truck itself.

The truck is the driver’s most prized possession; it is his source of livelihood and it is how he feeds his children. It is also his eternal companion. Egyptian truck drivers are not minimalists, and it is rare to see a truck of any size that is not richly decorated. Driving through Egyptian roads, the common practice of decorating trucks, with calligraphy, stickers and all manner of other object, is hard to miss. Serving several functions, the decorations’ first objective is safety and protection from the evil eye, hence the use of written verses from the Qur’an or Bible, or invocations for protection through the Prophet, saints or other holy persons. Decorative stickers spell out such invocations; specific quasi-religious themes, such as the Hand of Fatima, are represented across a range of mediums; and physical objects are also employed, like the hanging of a blue eye stone, prayer beads or a baby’s shoe. All are attempts to protect the truck and its driver from the dangers of the road, envy and the misfortunes of destiny.

Beyond the appeals to higher powers and the workings of fate, purely decorative motifs also abound. Illustrations and stickers of Disney characters, juxtaposed against the rough worn out trucks, are always ironic, while giant illustrations or sticker collages of fierce animals, like lions or eagles, promote a masculine aesthetic. There are also standard auto signage staples everywhere, like stop signs and hazard triangles.

Noha Zayed

Noha Zayed

Despite there being a taxonomy and catalogue of repeated or copied motifs, patterns and expressions, no two trucks are the same. This shows how the truck itself is a medium for self-expression. It is a chance for the driver’s socioeconomic reality to be presented through the mouthpiece of the driver’s heroic alter-ego, producing writing which includes not only verses from the Qur’an, hadiths and other expressions of faith – religion being the most popular cloth to wear – but also movie or song quotes, witty declarations, the nicknames of his children, his stances on love and women, a name he’s given the truck (‘the confused songbird’ and ‘monster of the road’ are some examples), statements reflecting the confidence of his own grandeur, declarations of advice, warnings or anything else that can reflect the driver’s philosophy, beliefs, dreams, ethics, or grievances. In a way, it becomes his public voice.

Noha Zayed

Noha Zayed

Noha Zayed

Noha Zayed

For myself, I imagine a further function, unconnected to the driver, one that I can’t quite put my finger on. From personal experience, it seems that just at the moment I need to know it, be reminded of it, be told of it – I look up and there it is, the message I was missing: a verse of scripture, a line of poetry, a quotation or a time-worn piece of advice. Serendipity always seems to rule the road – visually amusing, thought-provoking fun that always has me chasing them down the motorways to get a photograph.

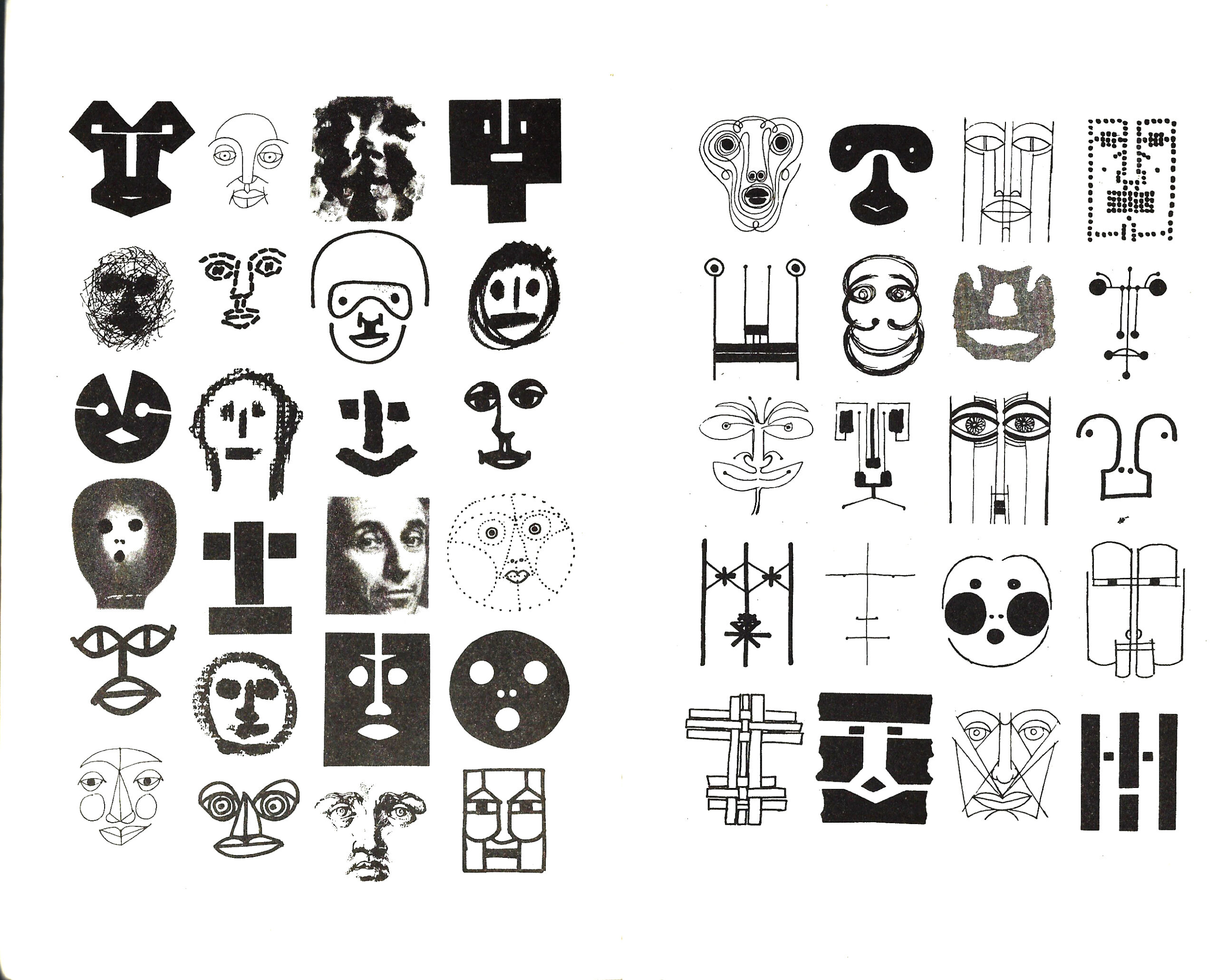

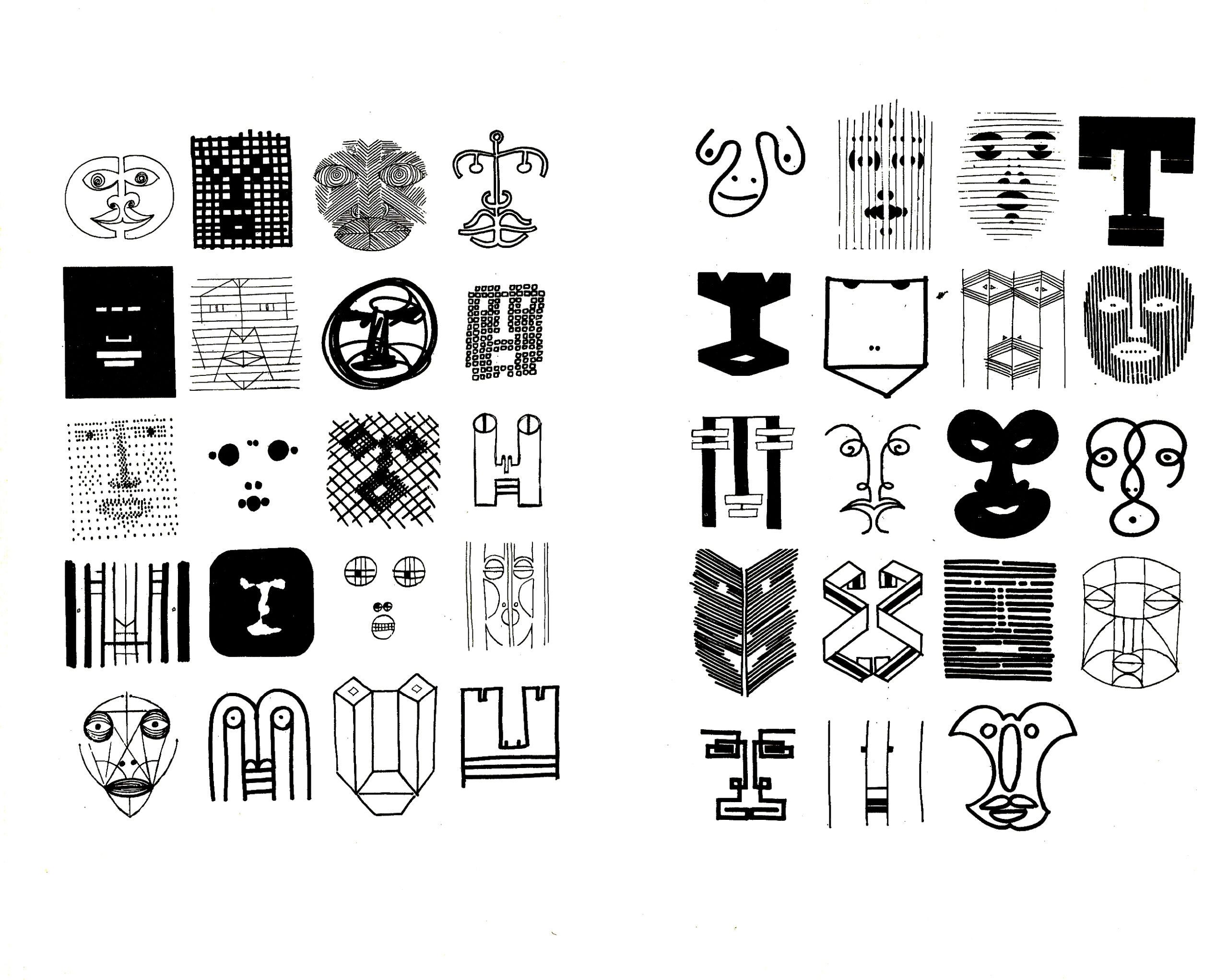

Language and Message:

Developing the Arabic script in Egypt

Travelling through the streets of Egypt, one cannot escape the overpowering role of language in the urban landscape. Words and phrases adorn buildings, vehicles, shopfronts and advertisements. Layers of time have rendered Egypt an urban palimpsest, where computer-generated fonts compete with traditional calligraphy and experimental lettering. The words on the streets are created by master artisans, graphic designers and craftsmen, and all have one common function: to communicate a message through language.

Thousands of years ago, the Ancient Egyptians were one of the first civilisations to utilise written language to communicate and preserve their existence. Their temples, tombs and papyri document royal and domestic affairs, tales of war, religious instructions, and even hymns and poems. Scribes attained a superior position in Pharaonic society where the art of writing was considered the language of the gods, closely associated with the divine. Not surprisingly, the language of Egyptians today, Arabic, is a descendant of hieroglyphics. The Arabic alphabet is derived from Nabatean, which descended from Phoenician, an offspring of the proto-Semitic alphabet. A small group of inscriptions (proto-Sinaitic) found at Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula – dating back to the sixteenth century BCE – are hypothesised to show an intermediate step between Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Phoenician alphabet developed in 1300 BCE. In pre-Islamic times, the Arabic script was established in North-Eastern Arabia and flourished in the fifth century CE among the Arabian tribes who inhabited Hirah and Anbar. It spread to Hijaz in Western Arabia, and its use was popularised among the aristocracy of Quraish, the tribe of the Prophet Muhammad.

Gamaliya

Warraq Island

In the seventh century, Islamic conquests moved from the Arabian Peninsula through the Middle East, North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, spreading the Arabic language and Islam. In a few decades, Arabic became a leading world language and the intellectual medium which united most of the civilised world.

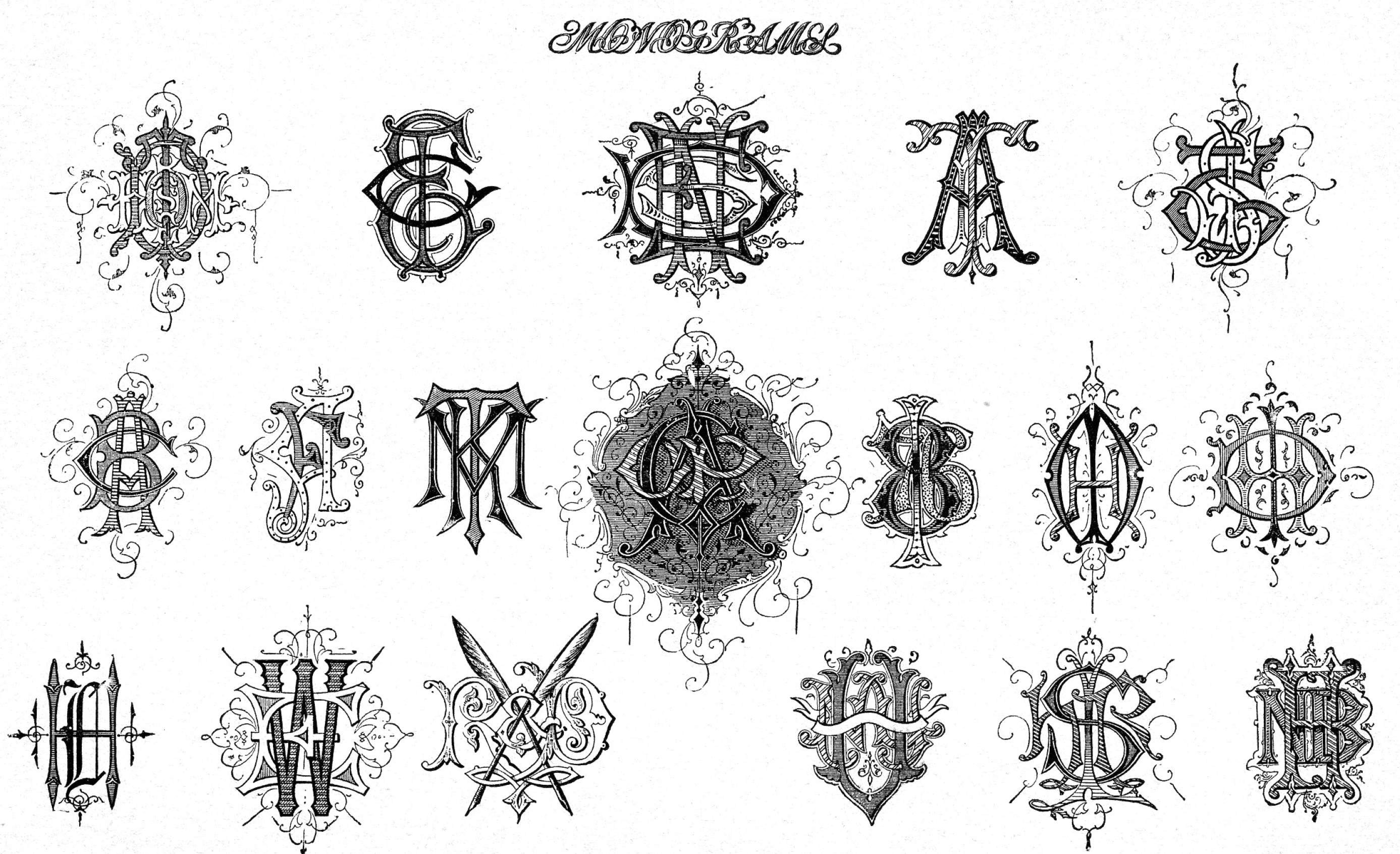

Arabic calligraphy flourished into its current system of discipline and elegance during the Islamic civilisation. Under the Umayyads and Abbasids, court requirements for correspondence and record-keeping resulted in many developments to the cursive scripts, and several styles were devised to fulfill these needs. Ibn Muqlah, (Abu Ali Muhammad Ibn Muqlah, 886–940 CE, Baghdad), was one of the most accomplished calligraphers of the Abbasid Age and the inventor of the Naskh script, the first proportional cursive style of Arabic calligraphy. His development and standardisation of cursive scripts, elevated them to a place of prominence, replacing Kufic as the standard for writing the Qur’an. A balance between clarity and aesthetic was crucial to the formation of this art form, which embodies a ‘disciplined freedom.’ Calligraphy reached its peak during the Ottoman era, when calligraphers invented and perfected several styles. They refined and developed the art of calligraphy over a period of nearly five hundred years, attaining the highest level of expertise in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The Khedival period of Egypt (1805–1914 CE) was marked by dramatic cultural changes, producing a visual culture that borrowed from European aesthetics. Muhammad Ali ruled Egypt from 1805–1849, and was often referred to by historians as the ‘founder of modern Egypt’, responsible for its reform and modernisation. As this cultural and economic period developed, so did the need for calligraphic applications on products, public spaces and state publications.

At first, calligraphic expressions were traditional manifestations of rule-based calligraphy (one that follows proportional standards) that reached prominence in the Ottoman era, and typography was confined to the limitations of the printing press and the rigidity of movable type.

Siwa Oasis

Then the 1879–1882 Egyptian revolt led by Ahmed Urabi, an officer in the Egyptian army, called for an end to the rule of Muhammad Ali’s family and to limit the European influence in Egypt. This signalled the birth of a primordial form of nationalism, one which celebrated Egypt’s heritage and geography. This nationalism was further bolstered by the 1919 revolution against the British occupation, led by a follower of Urabi, Saad Zaghloul, and other members of the Wafd party. The revolution, along with the establishment of the Wafd party, the birth of modern archaeology and the discovery and transporting of ancient Egyptian monuments into Europe, had a significant influence on Egypt’s intellectuals. Artists and writers, in pursuit of a national identity that rejected foreign occupation, extracted iconic forms from their visual heritage to represent what it meant to be truly Egyptian, and thus moved away from the power-laden mode of visual presentation attributed to colonial hegemonic power. During that time, the Royal School of Calligraphy was founded in Cairo in 1922 by King Fouad, and can be considered the first school in the Islamic world with the goal of preserving the art form by creating a new generation of skilled calligraphers.

Downtown

The creation of new political parties, rapid technological changes and development of the arts and media cultures all contributed to Egyptian society’s departure from the pre-colonial world. New image-making technologies were employed to serve political print cultures such as magazines, newspapers, banners and posters. Audiovisual industries including the film and music industries were significant components of popular culture. Industrialisation produced a consumer culture, and mass media contributed to expanding creative production. To support this, there was a need for typographic expression that the technology at the time could not provide. Calligraphers utilised their knowledge of the Arabic script and fused it with an experimental approach, creating modern manifestations of lettering that departed from Ottoman calligraphic standards. Simultaneously, many attempts at simplifying or even ‘Westernising’ the Arabic script were attempted, with the Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo leading a number of competitions in the 1930s to reform the script in order to work with Western printing conventions. However, many of these proposals were rejected, and hand calligraphy and lettering continued to dominate popular culture.

In the 1950s, Nasser’s nationalisation of the Suez Canal, major industries and the banking sector brought Egypt closer to a vision of self-sufficiency, producing everything from the ‘needle to the rocket’, as he preached in one of his iconic speeches. This created a need for the branding of Egyptian products to reflect an identity that was distinct from the Europeanised monarchy that preceded it, and this continued through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, where calligraphers were commissioned on a regular basis to render shop signs, movie posters, adverts, titles of books and magazines, and even newspaper headlines.

Today, Egypt is still considered a calligraphy hub that possesses a rich tradition of education and production, currently boasting 390 calligraphy schools, annually graduating 12,000 calligraphers. Despite this, Arabic calligraphy is still endangered. Digitisation of the Arabic script has led to the decline in the demand for hand-drawn lettering and calligraphy and beautifully rendered, hand-drawn urban expressions are replaced with computer-generated fonts that are often limited in their design. A key reason for the lack of quality of Arabic fonts used for commercial purposes is the slower development of Arabic type-design in the Middle East, due to the complex nature of the Arabic script along with technological limitations in addressing this complexity. This improved a great deal with the introduction of OpenType technology in the 1990s, which allowed type designers to integrate language-specific font behaviours and honour Arabic script grammar. However, access to well-designed typefaces remains limited to expert graphic designers with exclusive knowledge of software and typography. Furthermore, there are only about one hundred Arabic typefaces available to designers today, compared to thousands of fonts for Latin languages. As a result, the visual typographic expressions on the streets of Egypt are a mishmash of various hand lettering solutions, calligraphic expressions and digital fonts.

Downtown, Cairo

Arabic type design continues to evolve at a rapid pace, and young type designers, aided with enhanced technologies, are shattering the limitations of computer-generated fonts, allowing them to function in innovative and groundbreaking ways. Yet despite this, there is a nostalgia associated with handwritten lettering that can never be replaced with a digital alternative. A nostalgia that is potent in urban Egypt. You can see it in the faces of the people on the street, smell it in the hustle and bustle of the traffic, hear it in the sound of car horns and street vendors, and read it in the words that adorn everything you see, words that weave the rich and complex tapestry that is Egypt.

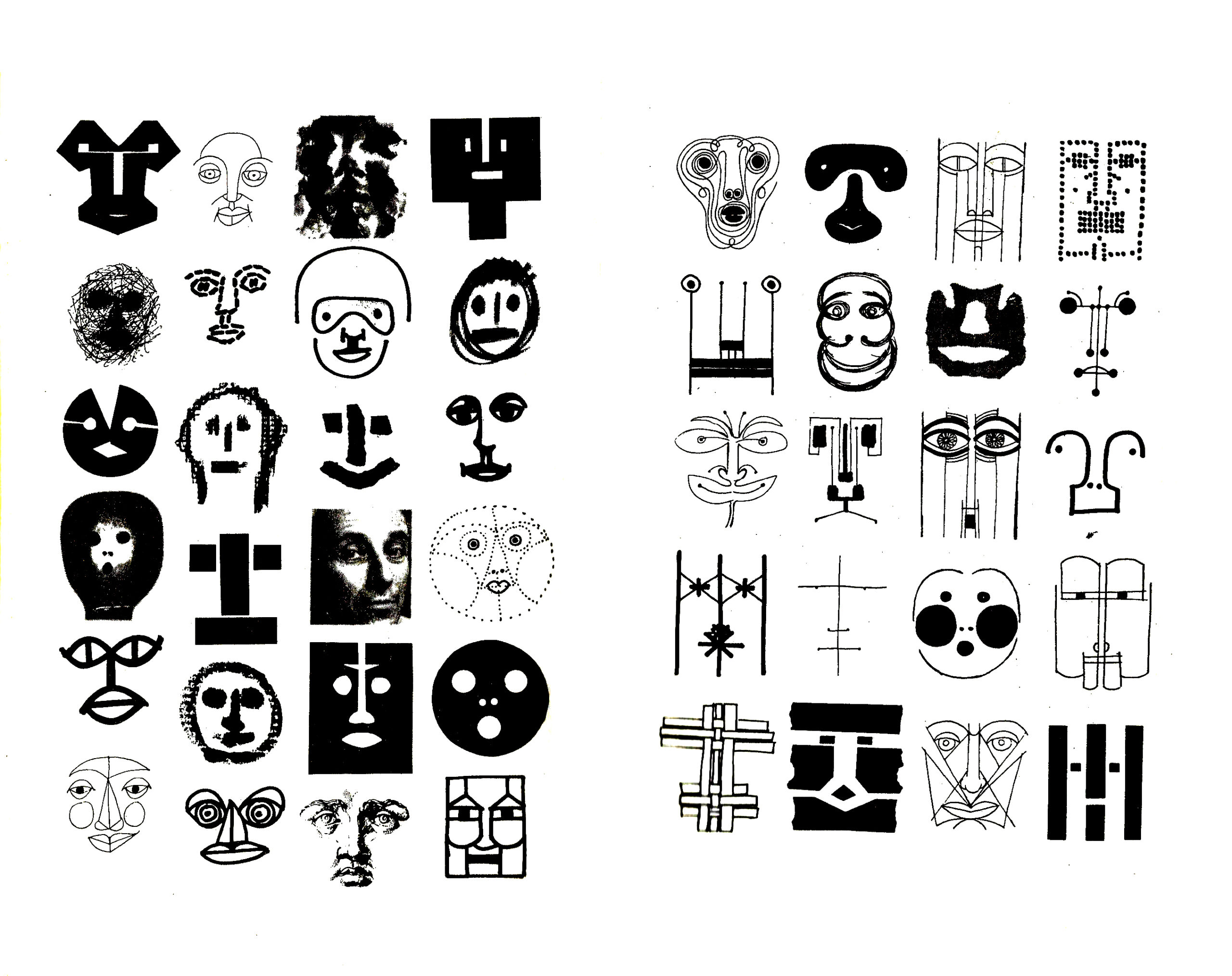

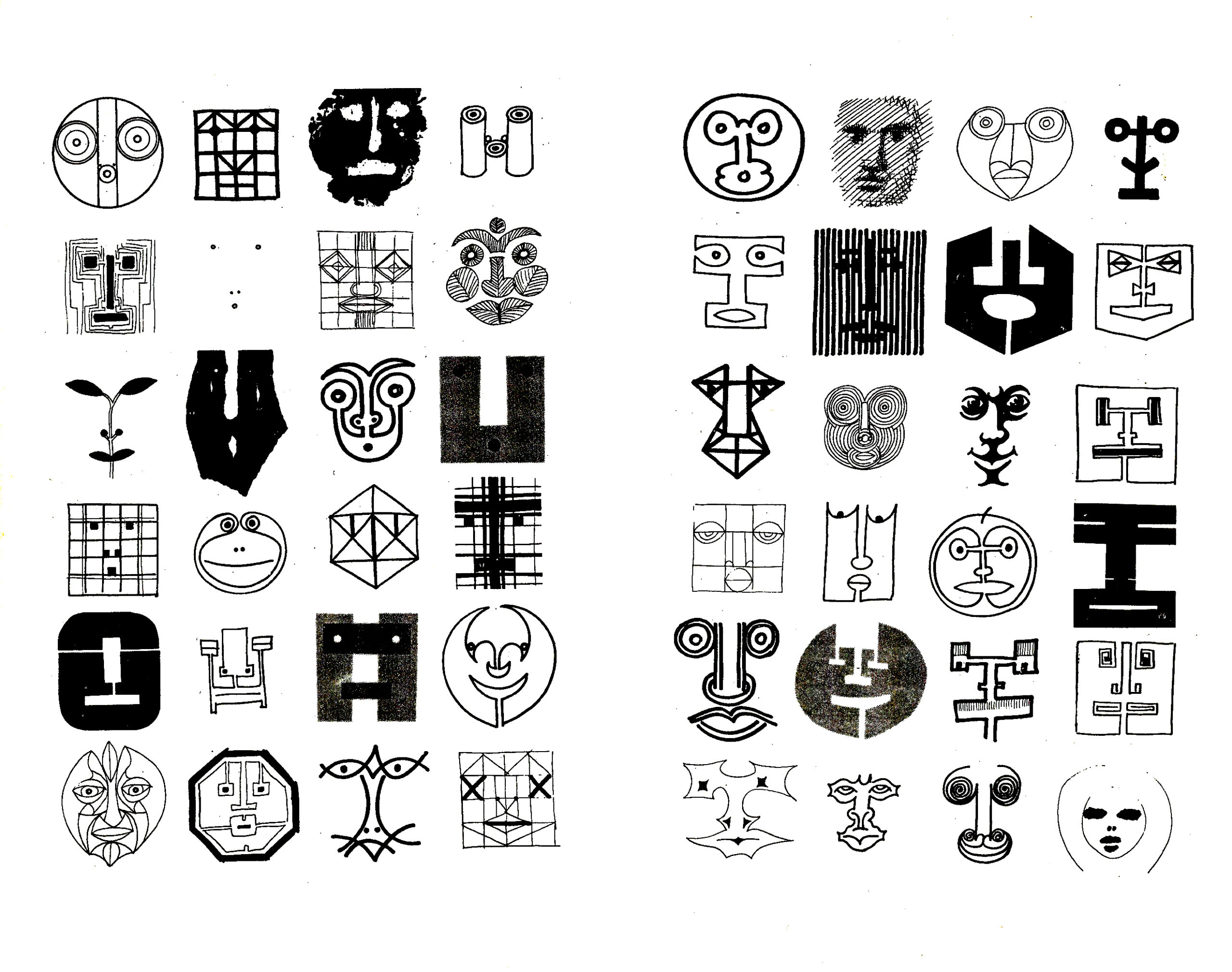

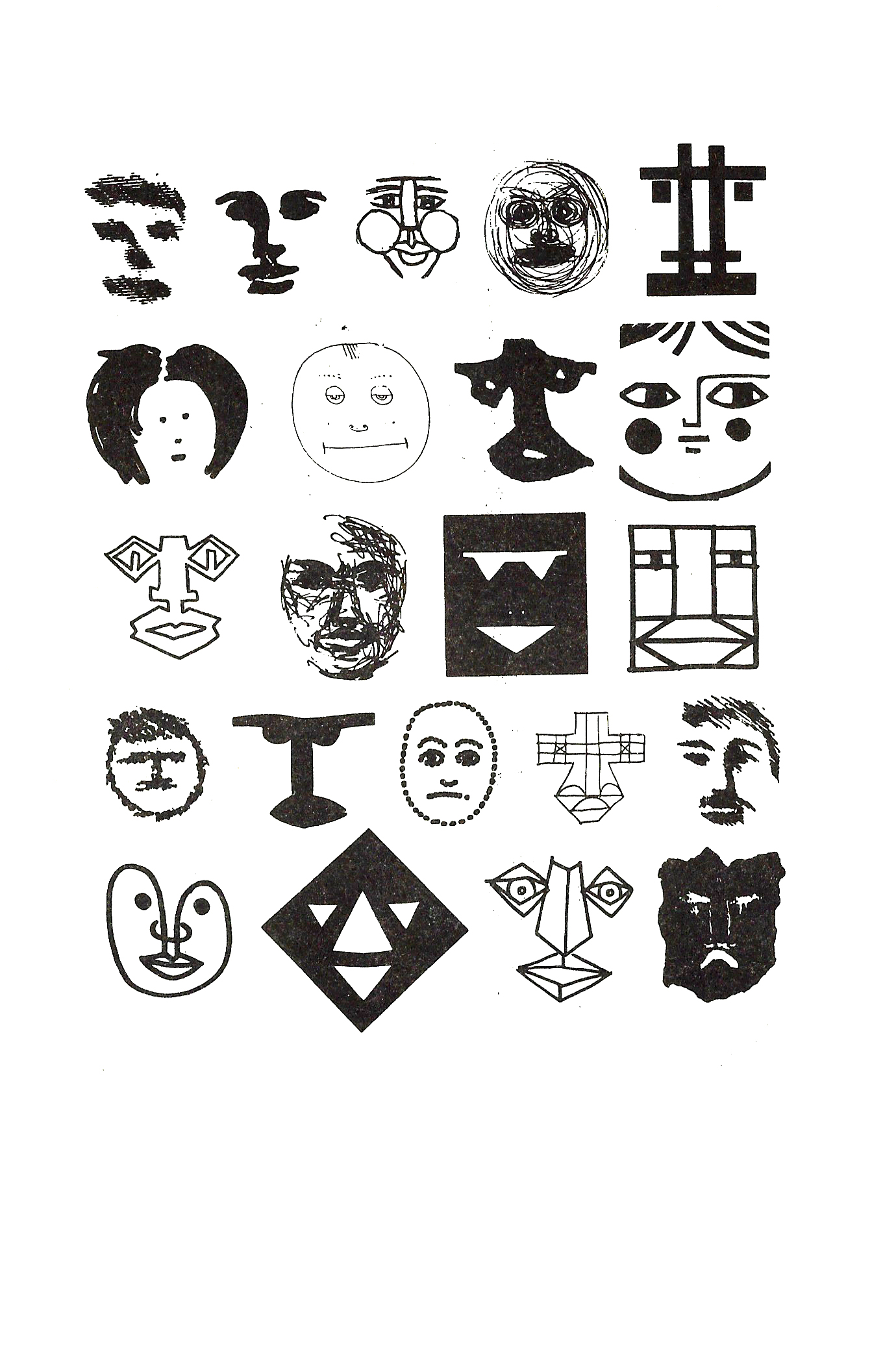

The Culture of Dummies:

A Mapping of Tutorialism

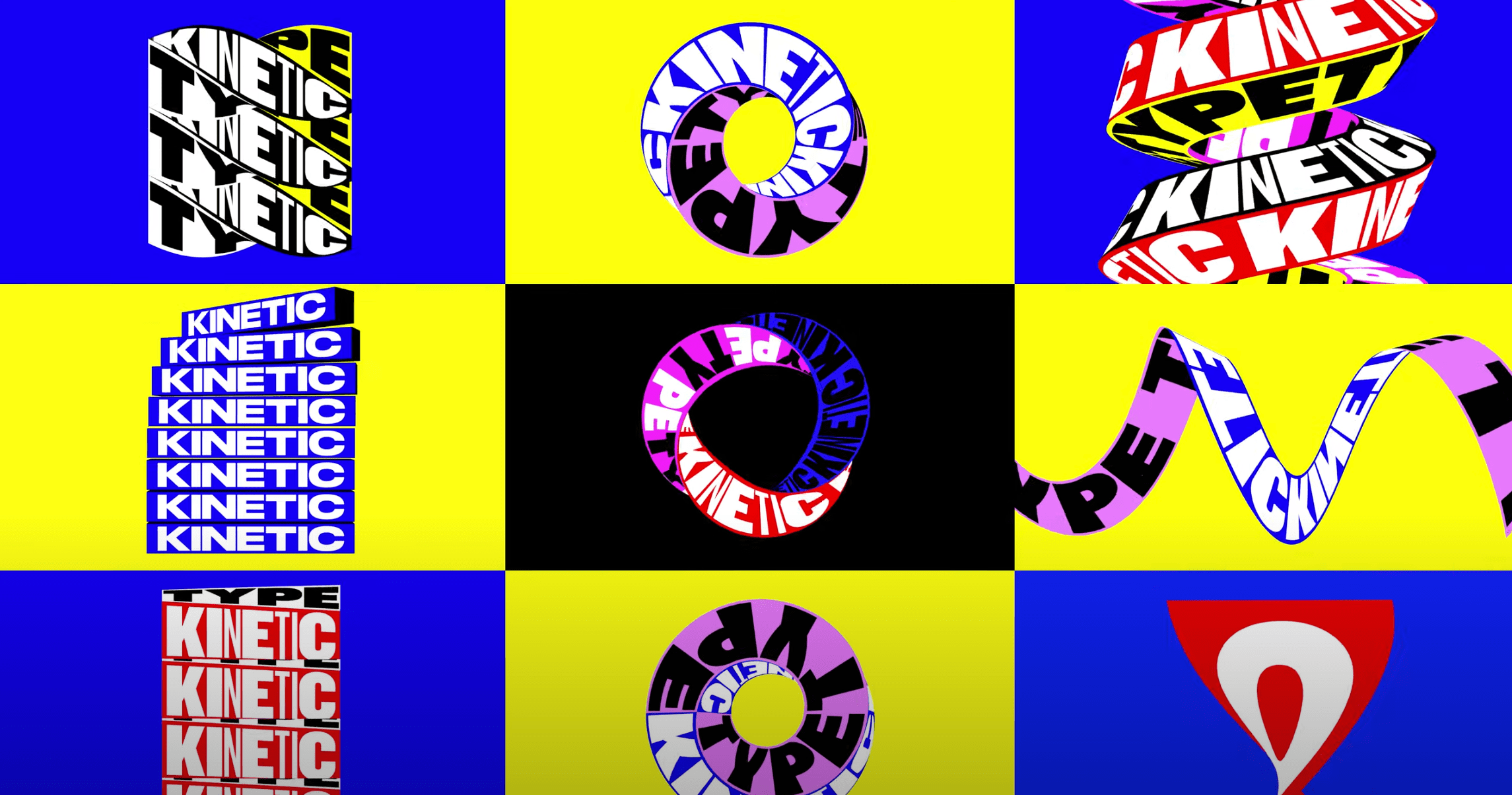

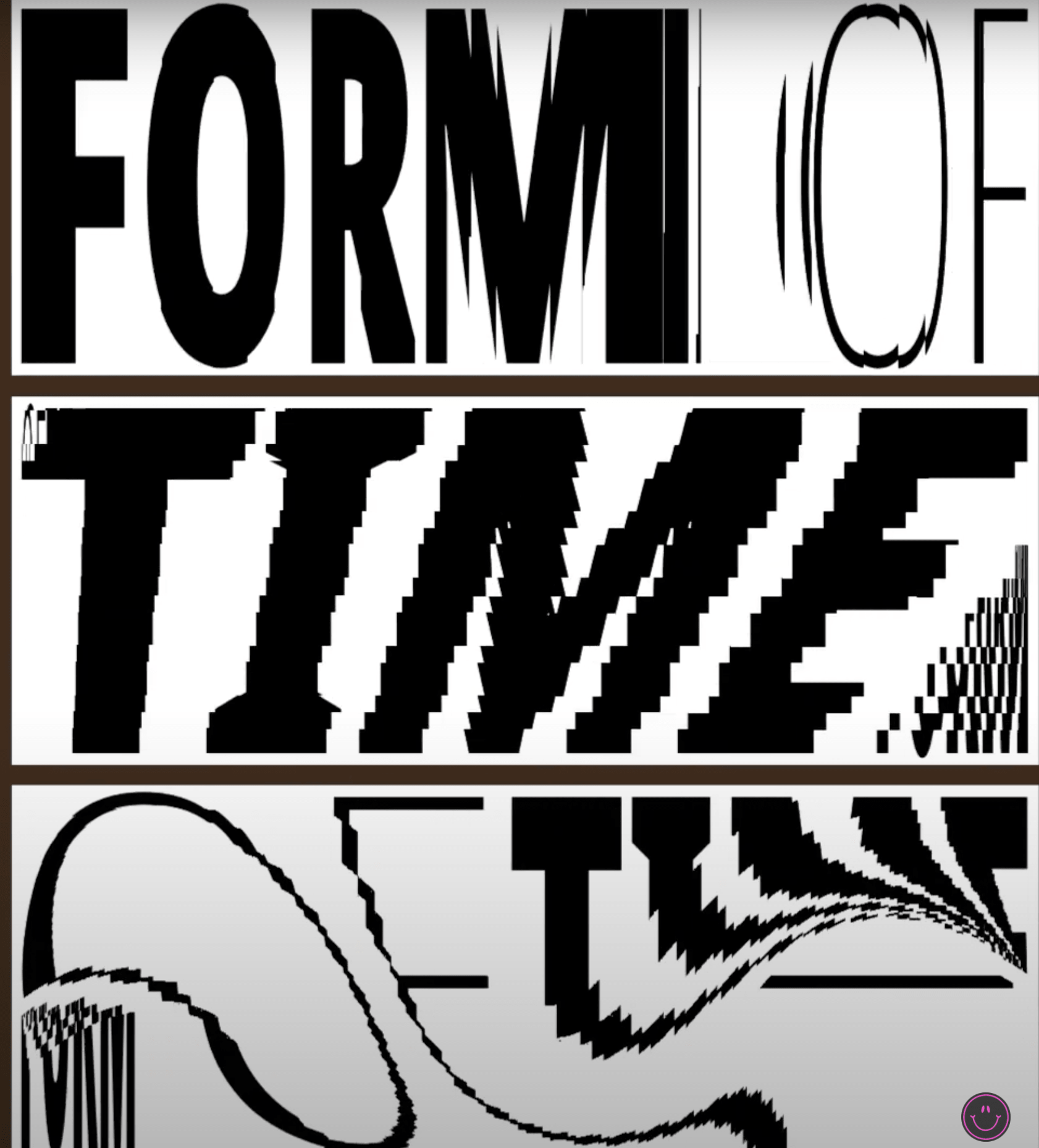

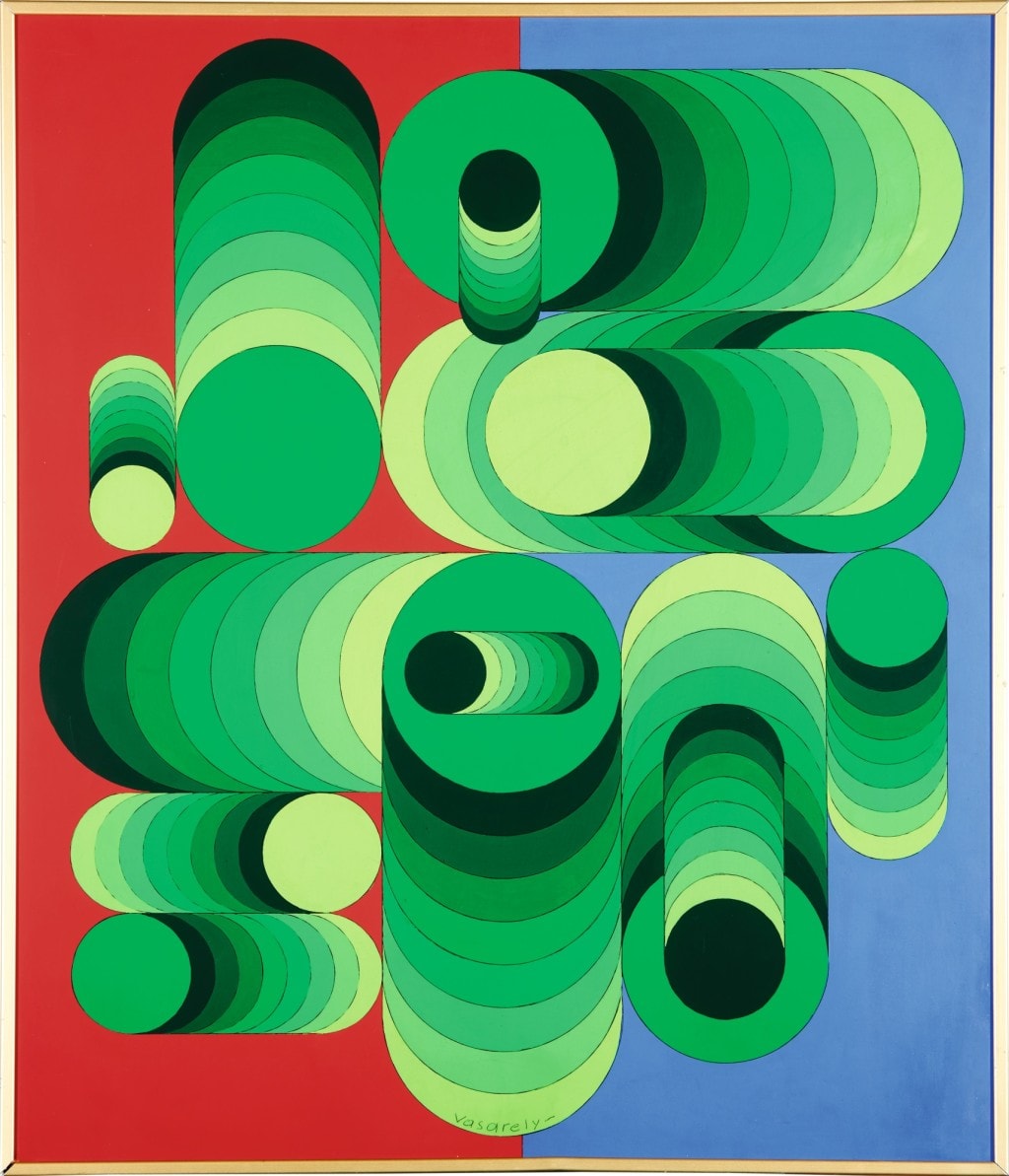

Above are a set of visuals, one taken from YouTube and another from Bridget Riley, a prominent figure from the Op Art movement. By a simple juxtaposition of the two, one can see the resemblance these visuals have to Op Art. An art enthusiast with an eye for design can easily bridge the connection between the two. However, upon further inspection, this resemblance is not the result of a deliberate decision that said designers came to revisit the Op Art and Kinetic movements. It was not by the natural means of drawing inspiration from the movements, examining the visuals further, and consequently, experimenting with the visuals in a modern context, on Adobe After Effects. It is rather sobering that this familiarity we are noting is the mere doing of these designers following the same YouTube tutorials.

These so-called “designers” have entered a rabbit hole of uniformity. On the one hand, there is the designer that put together the tutorial and curated most of the design choices that brought about a particular visual aesthetic, leaving countless designers, on the other hand, to use that same tutorial that may as well be dummy text – filling in their material and claiming it as their own. This is evident in a tutorial posted around a year ago on a YouTube channel called Dope Motions. The channel is owned by Nikhil Pawar, a Motion & Graphics Designer, according to the About section on his website. He released a series of tutorials demonstrating how the coupling of particular After Effects functions can lead to the creation of several visual languages.

Throughout the past year, a few more tutorials of the same nature were released by the same channel, now, with packs of ready-to-use templates available for purchase from a variety of websites.

What struck me was the heaps of young designers racing to imitate these tutorials, only to produce carbon copies of the original visuals. To make matters worse, the outcomes are then shared as novel design experimentation or as actual work.

Similarly, contrasting colors have shown a recent spike (coincidentally, the black and white trend is gradually dimming) following the introduction of a new flow of tutorials involving C4D and AE from a channel by the name of madebytiger. It goes by the same concept, except it features more 3D objects from C4D, pop colors and better lighting.

The same approach can be seen, but with more technical sophistication. Presenting bold typography and 3D effects, these tutorials have shown to be useful in my experience; upon watching a few, I have grasped a great deal of technical prowess and seen the untapped potential of After Effects and C4DI took the liberty to interview Tiger Zhang, the Boston-based designer behind the channel madebytiger, to gain insight into why he is creating these tutorials.