Prologue

I began working on this essay not knowing how industriously I would have to research it, nor how long it would turn out to be. The text you are presently reading is much longer than I had anticipated, and it is for this very reason that, as you will soon take note of, it ends rather abruptly. Consider it a work in progress, this article being the first iteration of many more to come.

Intro:

The recent history of Euro-American design is marked by three major events that have shaped the overall discourse around the discipline’s very history.

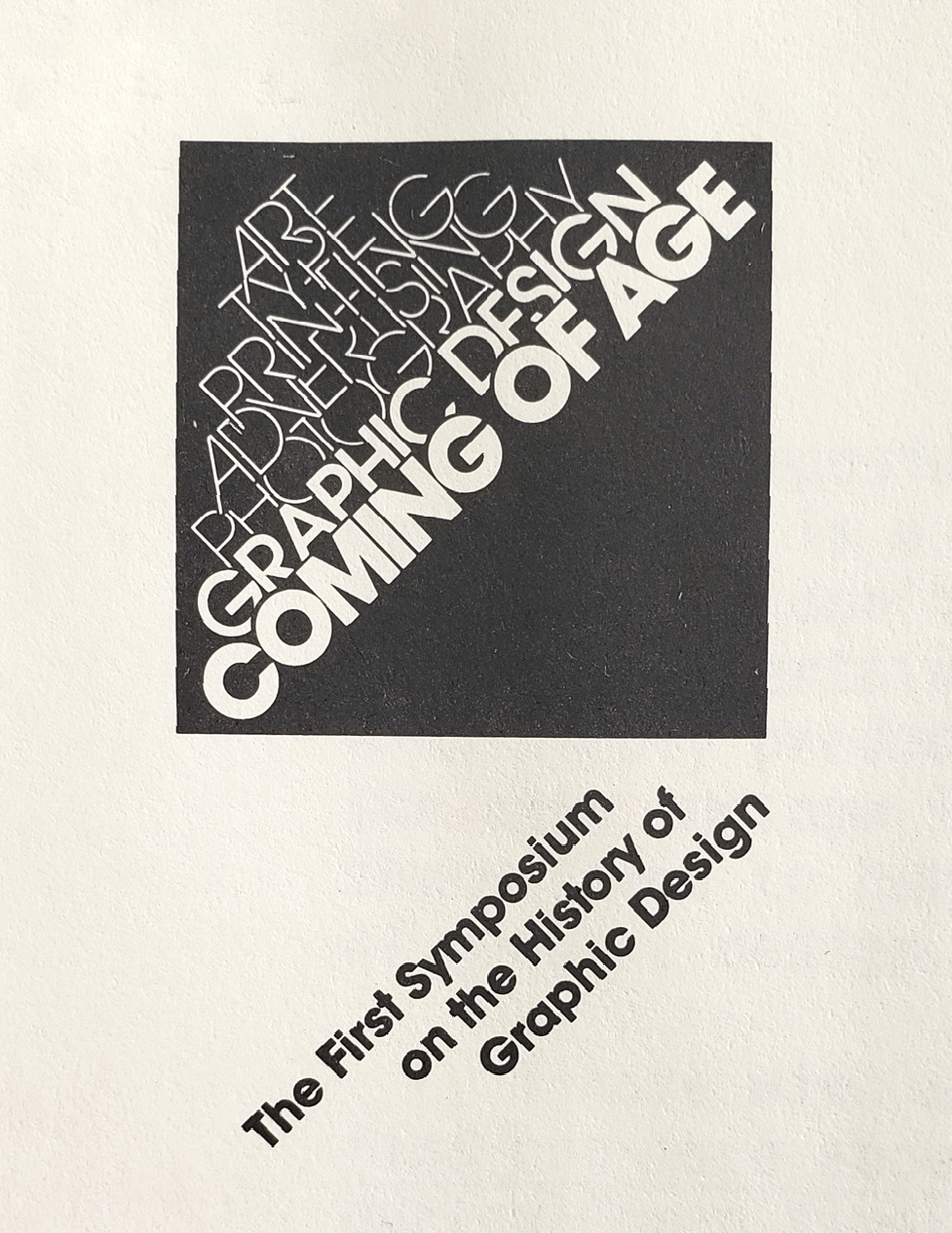

The first is “Coming of Age: The first symposium on the history of graphic design” at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in 1983. This symposium brought together academics, practitioners, and educators to highlight the already available events, individuals, and forces that contributed to what was defined as graphic design at that point. The organizers of the symposium Barbara Hodik and Roger Remington stated:

“The history of graphic design has been scattered among the pasts of art, printing, typography, photography, and advertising.”[1]Teal Triggs, Graphic Design History: Past, Present, and Future

The symposium marks a pivotal point in how the field conceived itself, and acknowledged the need to move away from art history as the underpinning foundation of design, and to consider a design history that takes into account other disciplines, including “sociology, anthropology, aesthetics, politics, economics”[2]Ibid – as Massimo Vignelli expressly called for in his keynote lecture. History, theory, criticism, documentation, and technology, he maintained, were all crucial for the progression of the design field.

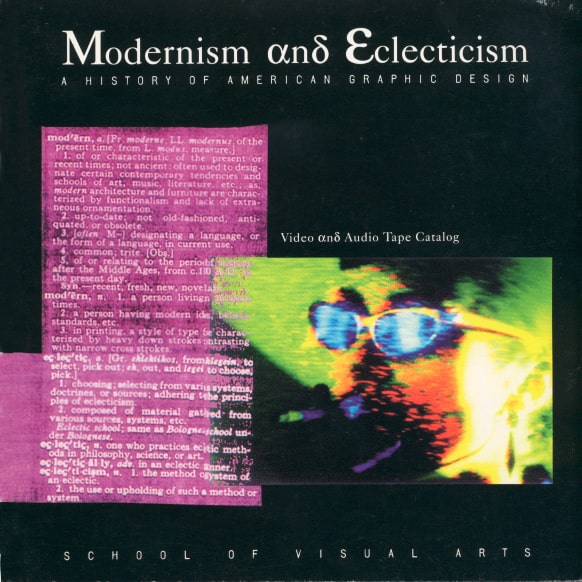

The second event was a series of conferences titled “Modernism and Eclecticism: A History of American Graphic Design,” which were organized in late 1980s and early 1990s [3]Ibid by Steven Heller, the art director of the New York Times, and Richard Wilde, then-chair of the BFA Advertising and BFA Design departments at the School of Visual Arts. These conferences were mainly focused on what Andrew Blauvelt called a “biographical hagiography,” which described the dominant focus, in this moment in Western design history, on the evolution of graphic styles, as seen in the works of canonical (mainly white male) designers [4]Blauvelt. Designer Finds History, Publishes Book, 2010. Both Andrew Blauvelt and Rick Poynor refer to Meggs’ A History of Graphic Design (1983) as the ultimate embodiment of this view of history.[5]Poynor. Out of the Studio: Graphic Design History and Visual Studies, 2011

The third event was a two-day symposium titled “New Views: Repositioning Graphic Design history,” which took place at the London College of Communication in 2005. The symposium questioned the dominant narratives of design history, which were mostly informed by the Western canon, and posed a few important questions: Whose history is it? And who gets to write it? The symposium presented several papers exploring the richness of graphic design history in countries such as Germany, Greece, India, Iran, and Mexico[6]Triggs. Graphic Design History: Past, Present, and Future, 2011 .

Since then, we have seen a shift in the prevailing discourse around the history of graphic design, and with it, another shift in the language used to broach the topic. We now speak of graphic design “histories” to reflect the plurality of narratives around the discipline, which exist beyond the Western design canon. This realization caused a renewed interest in not only our own history of design in the Arab region, but in many other graphic and visual histories globally. This consequently sparks the curiosity of not only the people to whom this history belongs, but a wider scope of research rangers.

While the debate around whether or not Western design history has the scholarly potential to stand on its own and be a field in and of itself – as opposed to being annexed to another, such as “visual studies,” which Rick Poynor, among others, argues is requisite for it to grow [7]Poynor. Out of the Studio: Graphic Design History and Visual Studies, 2011– we, in the Arab region, are still attempting at building the foundational historical knowledge that the field requires.

And so, now, the question for Arab designers, historians, and scholars is: will they adopt a responsible and dedicated apparatus for being involved in the creation of the discourses around our own history, or will they witness their own history being documented, studied, and interpreted by the West as part of its larger efforts of expanding its canon?

Over the past several decades, knowledge production around graphic and artistic practices in our region has been predominantly Eurocentric, with very few homegrown efforts to further explore or document our own cultural production. Let us consider, for example, the recent work in Islamic manuscript studies by the scholar François Déroche, author of the seminal book Islamic Codicology: An Introduction to the Study of Manuscripts in Arabic Script (2005), and Adam Gacek, who wrote Arabic Manuscript: A Vademecum for Readers (2009), to name a few.

Yet another the question for educational, governmental, private, and cultural institutions is: will they support these efforts if/when they arise?

Curious readers may read up on some challenges that faced the field in its early stages in these books: A History of Arab graphic design (2020) by Haytham Nawar and Bahia Shehab” ; Yara Khoury’s Nasri Khatar, A Modernist Typotect (2014) and Titus Nemth’s valuable Arabic Type-Making in the Machine Age (2017). Suffice to say that the challenges faced in those early days have been instrumental to where we are today. One of the main challenges that we continue to face to this day, and which is addressed in this essay, is the question of identity and that of continuity, and how one informs the other.

Some clues that may be able to help us formulate answers to these questions can be vaguely detected in our blurred visual memory, scattered deep within it. They are coded in the graphic work itself (or whatever remains of it). Designers’ attempts to engage with such questions rarely found their way in writing. Therefore, we are in the blind, for the most part, when it comes to how these designers conceived of these questions.

This, of course, doesn’t necessarily mean that such design writings are detrimental to us today, as we can surely formulate a reading of these design works in retrospect. But first, it would have given us a reading upon which we can juxtapose our readings today, and second, it would have given us historical context and insight on this moment from the point of view of design as it was practiced.

This early nonchalance towards documentation (of the work and in writing) made the prospect of progress or continuity extremely taxing. Indeed, anyone engaging with documented Arabic design work would attest to the fact that much of the work of designers born in the 1940s and 1950s was not well documented, nor was it preserved as it should have been, and therefore we find ourselves today tasked with doing historical patchwork.

Haytham Nawar and Bahia Shehab aptly put it in their survey book:

“Some designers simply refused to allow their work to be published. Still other designers have passed on without leaving behind an archive of their work; many of them were also artists who prioritized their art over their design practice, or their work was lost due to political unrest in their home countries.”

Mohieddine Ellabbad was one such person who lived this moment and had a sense of the importance of these practices to the future of the field of design. He said:

“New generations always start from Zero.”

Here, he was referring to the virtually nonexistent documentation and archival practices – not only of physical objects, but of thoughts and ideas – which are contributing to this rupture in history. That is one of the main reasons that Mohieddine Ellabbad wrote about design: to document his ideas, reflections, and observations.

This generation was comprised of mostly trained artists, a lot of whom wouldn’t fully embrace or commit to their design practice, as most scholars rightfully assert. Few were the ones who did.

This, of course, is not to say that there were no graphic productions taking place during the 1940s, a time that saw the dawn of modern Arabic graphic design. On the contrary, the region was exploding with great graphic engagement despite the latency of both individual and institutional acknowledgment of the field.

Now that the field is recognized and embraced, we are thus presented with a few pressing questions today: how can we move forward in the field of graphic design? What are these modes of progress?

Let’s take literature as an example. Would literature progress without the modes of both practice (literature) and thinking (literary theory)? No, it cannot. What literary theory offers, in very simple terms, is thinking about writing, reading, and language – the very thing that is missing in design and design writing.

One of the major challenges that Arabic design is facing today is that it is currently soaked in practice and lacks the kind of reflective thinking and historical context that is offered by writing. We should think of both practice and writing as the two main pillars on which the domain of design can erect and writing is where this mode of thinking about designing can be fully explored. One could also argue that the field of Arab design cannot ever reach its full potential until we reach technological independence, and progress in other domains that are linked or overlap with design.

Therefore, one need not to make a case for the importance of writing in the progression of any domain. Yet despite its undeniable importance, the field of graphic design still suffers from an acute deficit in writing.

That is not to say that there are no writings about Arab design at all – I reference some good examples at the end of the essay – but what is already published is not merely enough, let alone thorough or comprehensive. Even good sources or studies exist, though not without their baggage and limitations, and each with some degree of inaccessibility to the wider design community. Most of these can only be found on:

۞ Membership-based academic platforms (mostly Western).

۞ University portals or university libraries under Ph.D. titles.

۞ Books which, depending on where you reside in the Arab region, can be beyond reach due to logistical or economic difficulties, and are thus only accessible to some.

۞ The offshoot magazine or article.

Despite the abundance of visual – both current and historical – output we have, the field in Egypt and the region at large is left with textual production that is insufficient, as evidenced by a ratio of design writings to design productions that is ineffably tilted.

There is also something important to clarify before delving further. When I say writing, I don’t just mean writing books, which we have started to see glimpses of, but I also mean all other forms of writing, as numerous as they may be, but especially the kind of writing that is self-reflective and research-based.

One of the greatest examples in recent history of how design and writing can be in unison is the school of Mohieddine Ellabbad (1940-2010), a school that valued and integrated design writing as an integral part of being a designer. Yet, we know very little about it. The present essay will merely scratch the surface of this school, and will focus on expanding what we know about it through an inquiry into Mohieddine Ellabbad’s establishment of the “Arab Graphic Centre” and the Arab workshop for children’s books in 1976.

A thorough understanding of this initiative is of essence, especially because it attempts to engage with the questions I raised above, which we are still grappling with to this day.

Anyone who knew Mohieddine Ellabbad would submit that his life was particularly challenging. On the one hand, his was a generation that experienced myriad socio-political challenges – the global complications of the cold war; the Arab Israeli war; the rise of the Palestinian resistance; to name a few – and on the other, his rigorousness and criticality were a double-edged sword, often relegating him to the sidelines.

Despite these challenges, Mohieddine Ellabbad remained committed to his work ethic, and to what he believed was vital to the profession. So, the best way to start this essay is by echoing Mohieddine Ellabbad’s spirit of criticality, humbleness, and skepticism and by letting those be my guiding principles throughout the essay.

In his spirit, I write.

First, let’s take a closer look at the current landscape of writing available about Mohieddine Ellabbad. One such repository of writings can be found on the Faculty of Fine Arts’ portal, where every “supposed artist” is featured i.e. everyone who comes out of the academy, despite the fact that some of them may identify as designers or otherwise. On this portal, everyone has an entry page with different tabs you can toggle between: their CV, some of their work, and a “Their vision” section.

The “Their vision” section is a crucial one to question and unpack, as this is where writing about Mohieddine Ellabbad lives – or more accurately, dies, because these texts are given eminence that assumes false totality and comprehensiveness through the sense of legitimacy bestowed by the academy. On this page, readers are presented with a plethora of piled written texts, which at first glance, can be exciting but, upon closer reading, all but disappoint. The Faculty of Fine Arts curated a selection of written pieces about Mohieddine Ellabbad, and we, as readers, are supposed to synthesize his vision in and through these writings. This is not to say that there is anything at fault, per se, in the featured writings themselves; but rather, that this part of the essay ought to question the mode of inquiry deployed in these writings – the selection criteria, the republishing method, and structure of these pieces.

Here you can view the written pieces on the portal.

To summarize, the list above includes a total of 32 pieces, 25 of which were written in 2010 – the year he passed away, amounting to a staggering 75% of the total – another one of which written in 2016, and yet another which is repeated twice, once under the year 1998, and once under the year 1988.

Mode of Inquiry: Is there even any?

The term “modes of inquiry” is used within research practices to describe the systems and methods deployed by researchers and scholars to investigate, explore, or identify questions of interest about their topic. These modes, as numerous as they may be, often lead to a conclusive outcome or contribute to the discourse in the field by giving rise to more questions. And so, when viewing these pieces, readers can conclude that none of them contain any actual mode of inquiry that is derived from a question of interest.

Astute readers will quickly register that the writings featured on the Faculty of Fine Arts portal are journalistic productions, and not research-oriented writings. This very fact is indicative of one of two conjectures: either this is what the academy considers to be “good” design writing; or there is a genuine lack of more critical, in-depth writing, especially in graphic design.

Criteria of Selection: A Broken logic

Attentive readers will also be able to deduce that the overarching method of selection is predicated on the following logic in curating these pieces:

- If the author of the piece is well-known, then the piece is by default a good one, and is allowed admission to this pantheon.

- Should that prove to be the case, the text does not undergo any editing, fact checking, or revision (given the many inaccurate facts, spelling mistakes, and even the inclusion of the same text twice).

- That these pieces can fulfill their function without providing a wider context to readers.

- That there is no need to consider these texts together and see if they are providing a multiplicity of readings or diverse understanding of the subject.

- That the academy has the authority to alter the original form that the text appeared in – including removing images or changing the formatting – and that this won’t affect the reading of the piece (which is not the same as editorial revisions).

- That quantity trumps quality.

These assumptions are manifested in the curated pieces available on this page. What the Faculty of Fine Arts has essentially done is dump these texts in one space, without questioning their content, nor whether or not this kind of writing is appropriate to both the subject or where it is being republished.

The structure

Language (Title and Titles)

The form or structure of these pieces falls under one or more of these categories:

- Testimonials

- Eulogies

- Commemoration letters

- Personal stories and anecdotes

- Quotes

- Paraphrasing

Most of these categories are replete with recycled information. They utilize ready-made modules that constitute an invisible writing structure, in which different fragments are sometimes combined or rearranged to give the illusion of novelty when this “new” text is presented.

Language:

Most of these texts use ambiguous, loaded, and packed language, while refraining from unpacking or elaborating on them. They are assertive in nature, not propositional, which is to say that information is presented as definitive and not as material of discourse. This kind of language deploys hyper-poetic forms of empty rhetoric that can bestow the text with an enchanting, albeit ultimately empty, quality.

This kind of poetic approach to writing can be said to be used as a medium for masking a poverty of knowledge and inaction. It is more concerned with linguistic acrobatics than the subject itself. Ultimately, such writings do not offer much, if any, substance, and do not stand up to intellectually rigorous scrutiny.

Titles:

Another important part of the structure is the language employed in the titles of these pieces. When we juxtapose the titles with the actual content, one notices a tendency to hyperbolize the title in relation to the content of the piece.

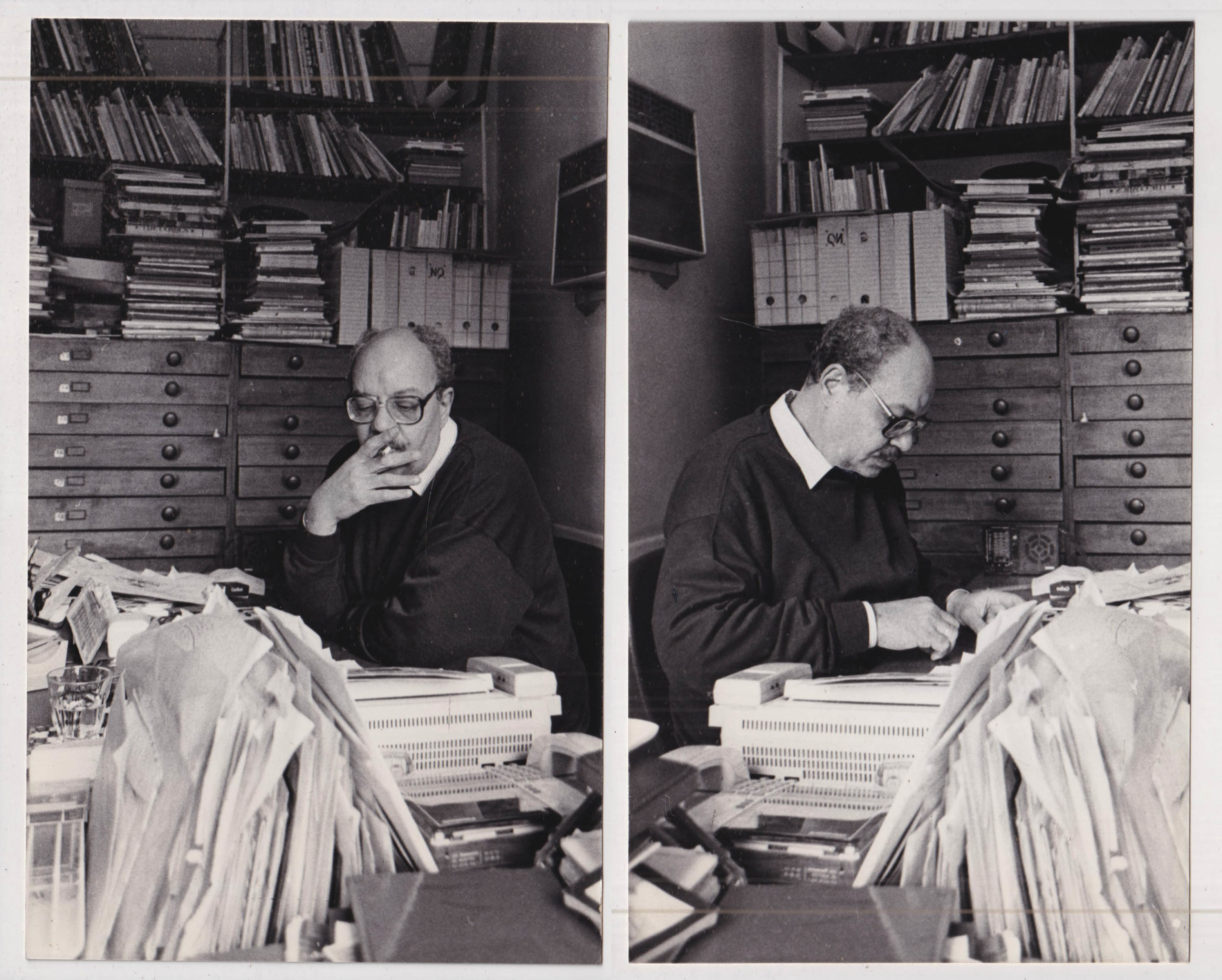

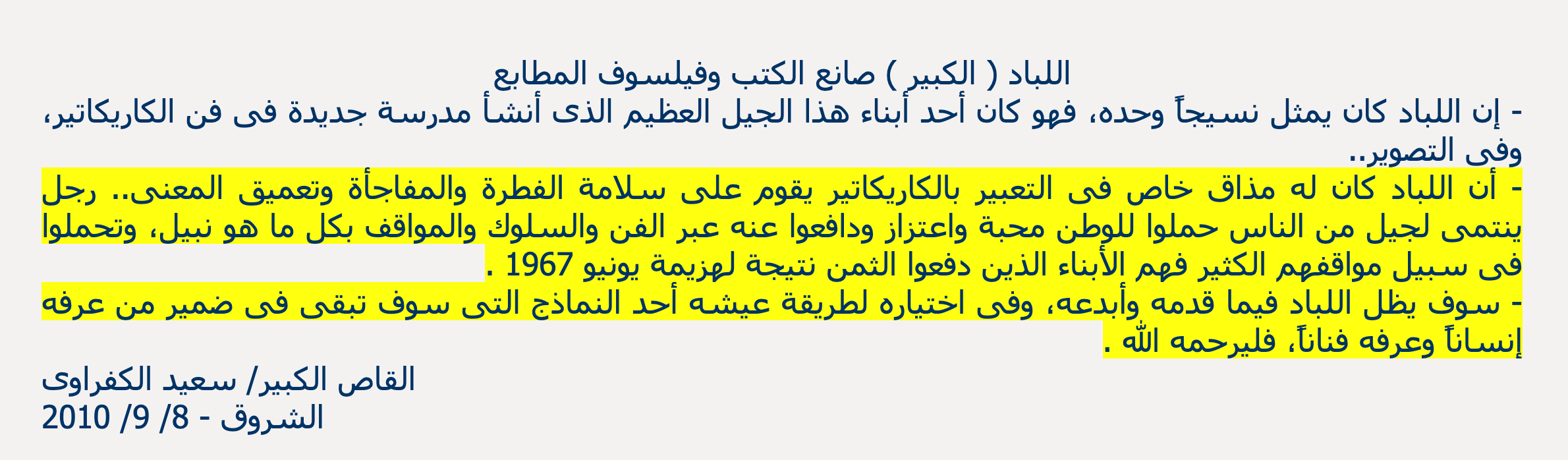

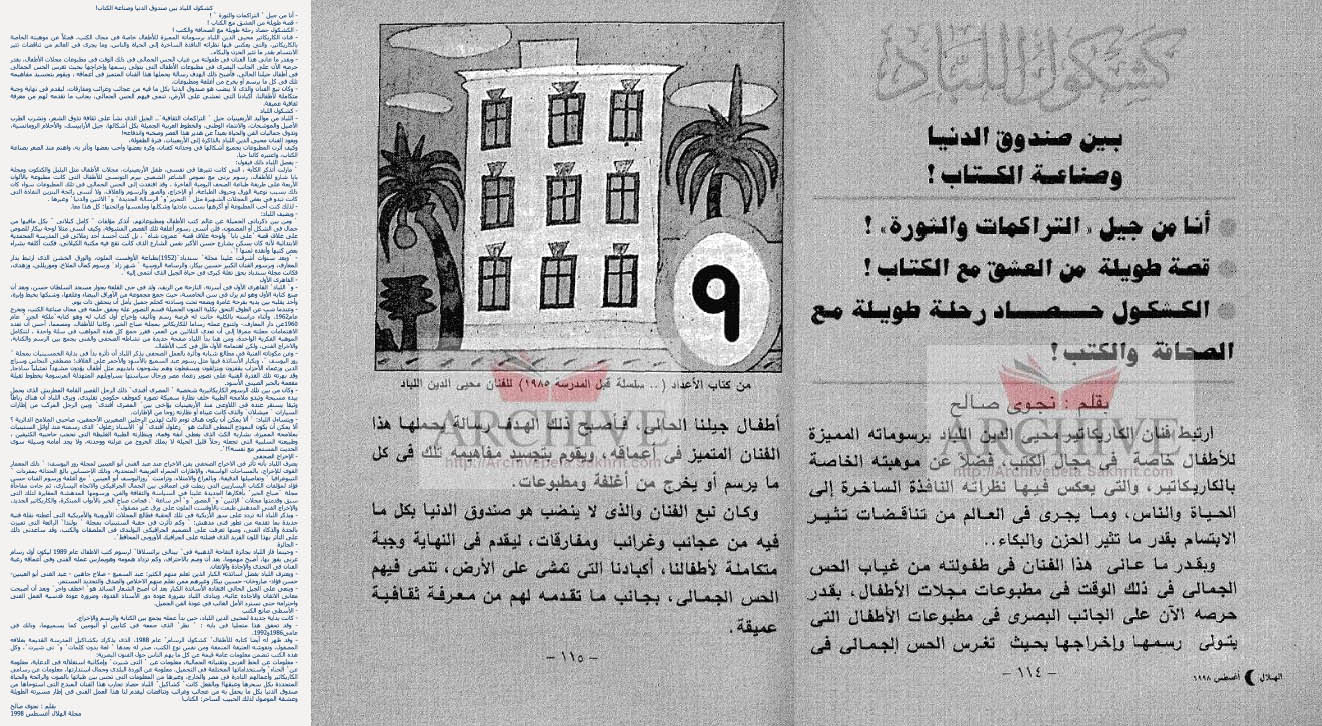

To illustrate, let’s extract one piece that perfectly embodies this point.

Translation:

Title:

Ellabbad (The Great), bookmaker and printmaking philosopher

Body text:

Ellabbad alone constituted a fabric. His was a great generation, and he managed to establish a new school in the art of caricature and painting.

Ellabbad was unique in his ability to create caricatures that draw on instinct, a sense of surprise, and a deepening meaning. He belonged to a generation that had great regard and pride for their country, and defended it through art, mannerism, and noble stances. They endured much for the sake of these stances. They are the ones who paid the price as a result of the June 1967 defeat.

Ellabbad lives on through his innovations and all that he had to offer, and in how he chose to live his life, which will be seared in the memory of those who knew him both as a man and as an artist.

The title suggests that something of great significance is about to be conveyed, but only a few sentences follow that use a form of eulogy, which does not address or elaborate on the grand statements put forward in the title: How was Mohieddine Ellabbad a philosopher of printmaking? What is this philosophy?

Republishing:

Many of the pieces featured here were initially published elsewhere, so the previous critique is of the version that is re-published on the Faculty of Fine Arts portal. Still, there is something to be said about what happened to these pieces when they move from their original publishing platform to the Faculty of Fine Arts portal. One would assume that nothing should happen to them, or, if anything, that maybe some extra quality control measures were taken by the academy. But somehow, these texts were downgraded even further in that process.

The original form that these articles appeared in, whether a magazine or a newspaper, might have had images that accompany the piece, and thus the academy, for whatever reason, have excluded these images when reproducing these texts on its portal, which would in turn compromise these already fragile articles. This, in a way, exposes the text even further. The written pieces now appear naked to the eye of the observer.

Let’s also illustrate.

Here is another example:

After a close scrutiny of these texts, we can now gauge the general characteristics of writings on the Faculty of Fine Arts website. The portal becomes a graveyard of design writing, and what is missing there is writing that sets an example: the kind of writing that can spark a discourse and offer a multitude of viewpoints, which in turn makes way for a plurality of readings about a person or subject, that exhibits how writing can illuminate ideas and meaning in design work.

Think about the different kinds of visitors of the portal. The kind of writing that is found there does not present the subject in a way that can spark curiosity – not because the subject itself isn’t interesting, but because the writing about this very subject is flat in and of itself.

What do we get out of any piece we are reading? What makes a good piece of writing?

A helpful set of questions are suggested by the designer Khoi Vinh, which you can view here.

Another locus where you can find an account about Mohieddine Ellabbad is A History of Arab Graphic Design (2020). Though by no means comprehensive nor without fault, this publication nevertheless comprises an important inventory – perhaps the first of its kind – of practitioners who contributed to Arab visual culture. Far from being encyclopedic, the book has been praised by design practitioners, the media, and scholars.

Evidently, the book features Mohieddine Ellabbad among its list of designers. However, what it offers is a slightly more organized assortment of the scattered pieces found online, with a few extra images here and there, though without adding any real nuance to Mohieddine Ellabad’s work.

The book is celebrated as the first of its kind – and it is – but on its own, it is not enough. A close and curious reading of Mohieddine Ellabbad’s entry reveals some shortcomings, especially the part about his attempt to establish the Arabic Graphic Centre. The authors of the book claim that:

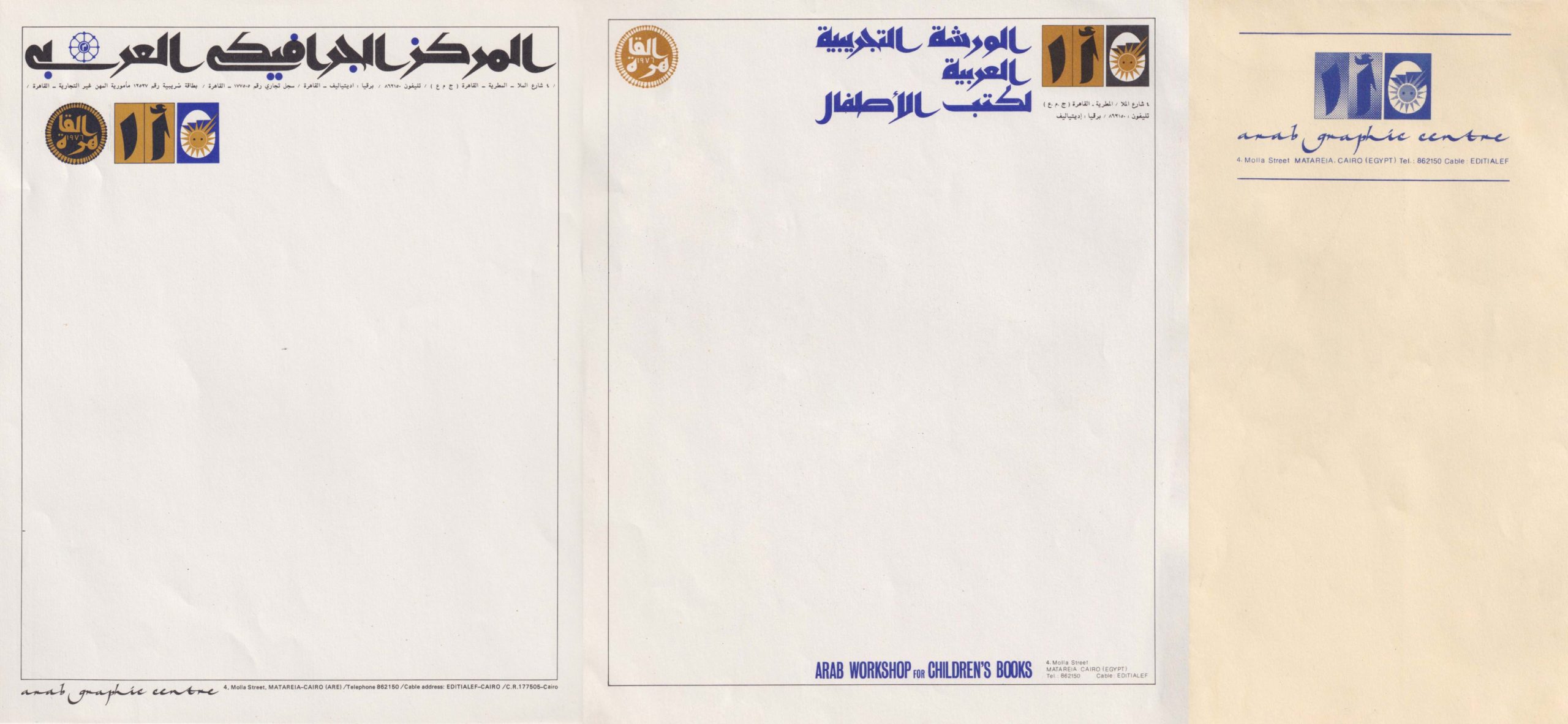

In 1976, he established the first graphic design center in Egypt: al-Warsha al-Tajribya al-‘Arabiya li-Kutub al-Atfal (the Arab Experimental Workshop for Children’s Books).

This excerpt presents this information as factual, but this can be contested. What is understood from this statement is that the Arab Graphic Centre is the same entity as the Arab Experimental Workshop for Children’s Books.

Translation:

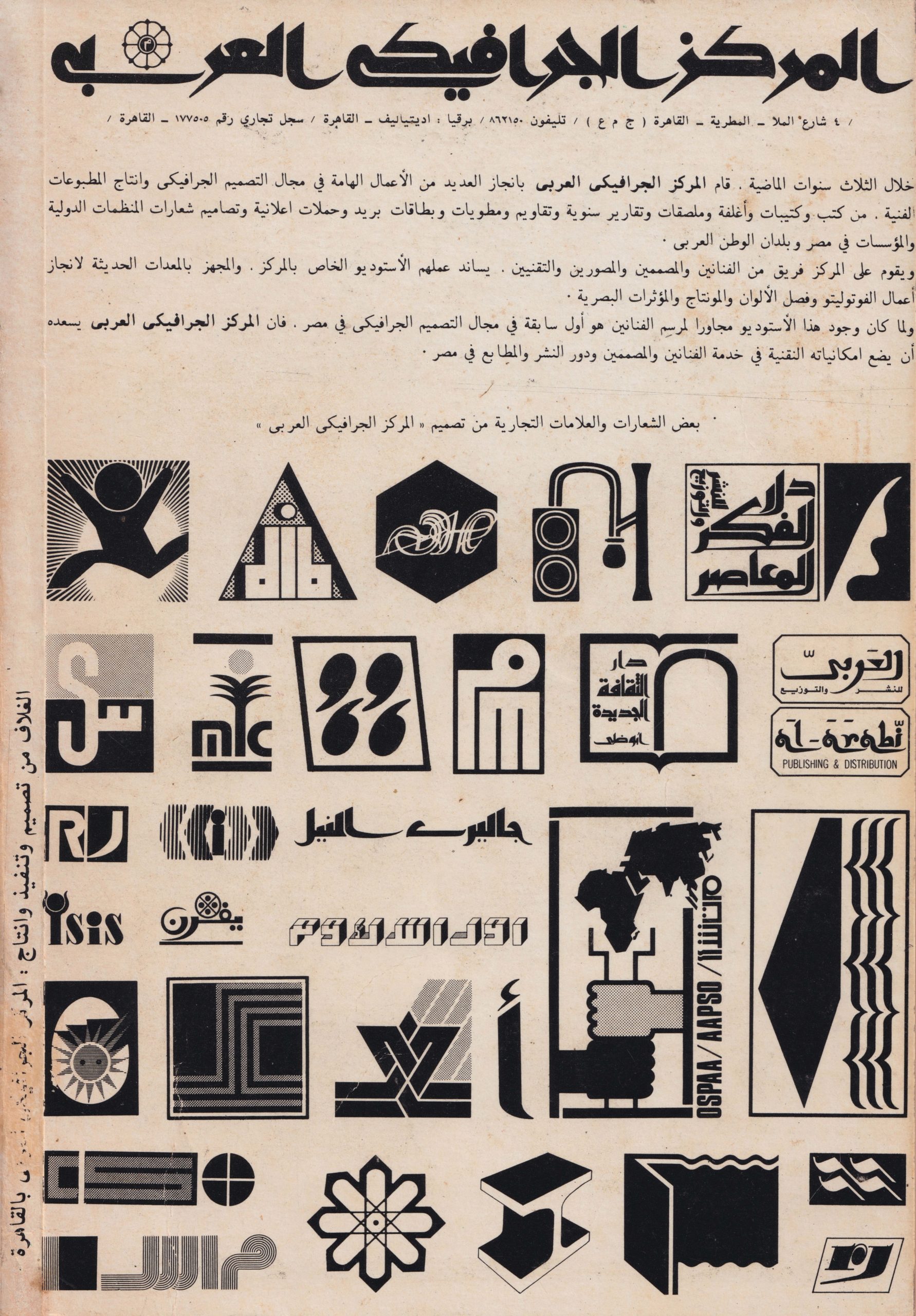

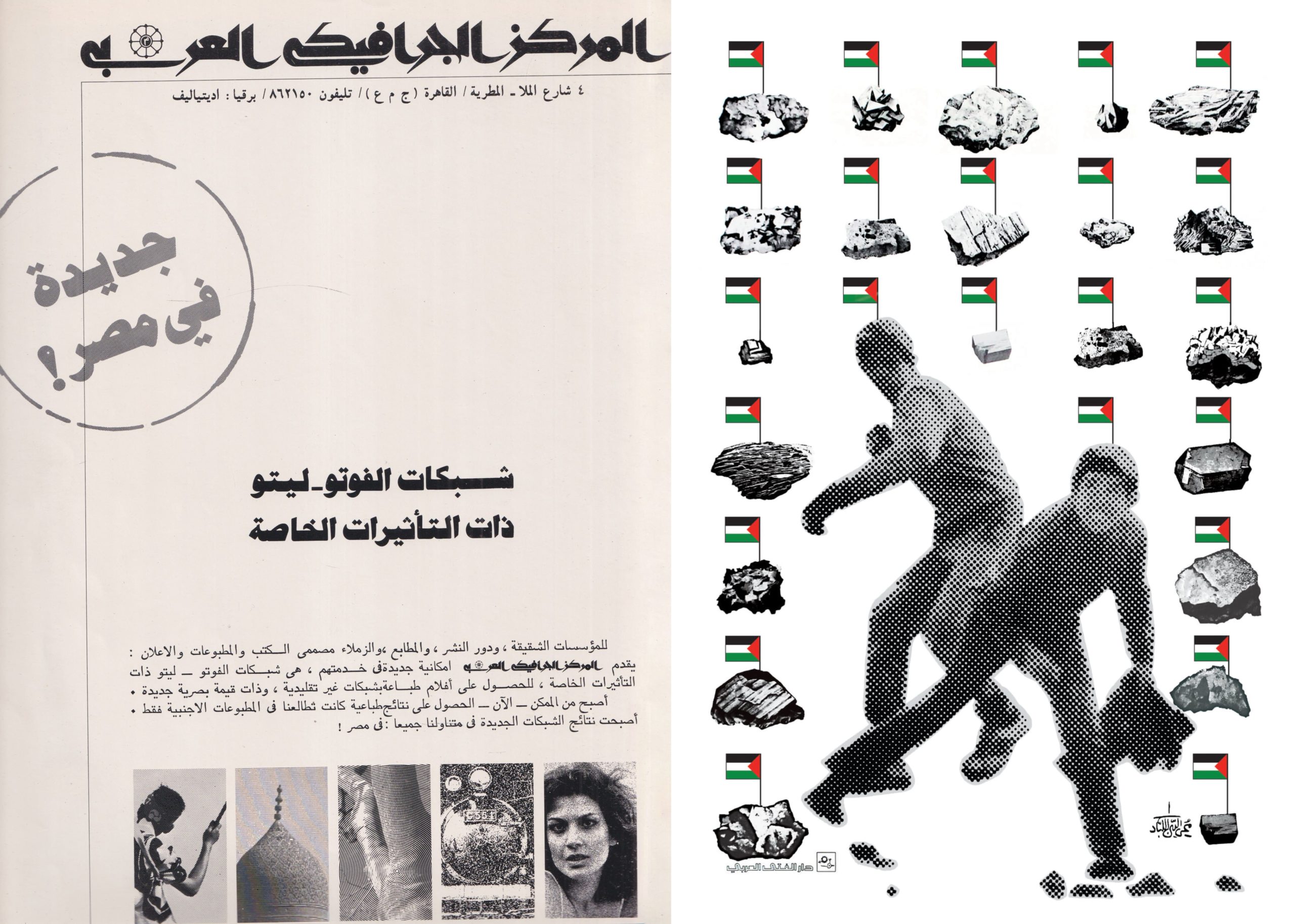

“Over the past three years, the Arab Graphic Centre produced many essential works in the field of graphic design and publishing of art prints, from books, booklets, covers, posters, annual reports, calendars, brochures, postcards, ad campaigns, and logos for international, regional, and local institutions.

The centre consists of a team of artists, designers, photographers, and technicians. It features an in-house studio equipped with the newest machinery at the time to help make photolithography, color separation process, montage, and visual effects.

Since this studio is located in the vicinity of artists’ studios, it is the first of its kind in the graphic design field in Egypt. The Arab Graphic Centre is thrilled to offer these technical tools at the service of the artists, designers, publishers, and printing houses in Egypt.”

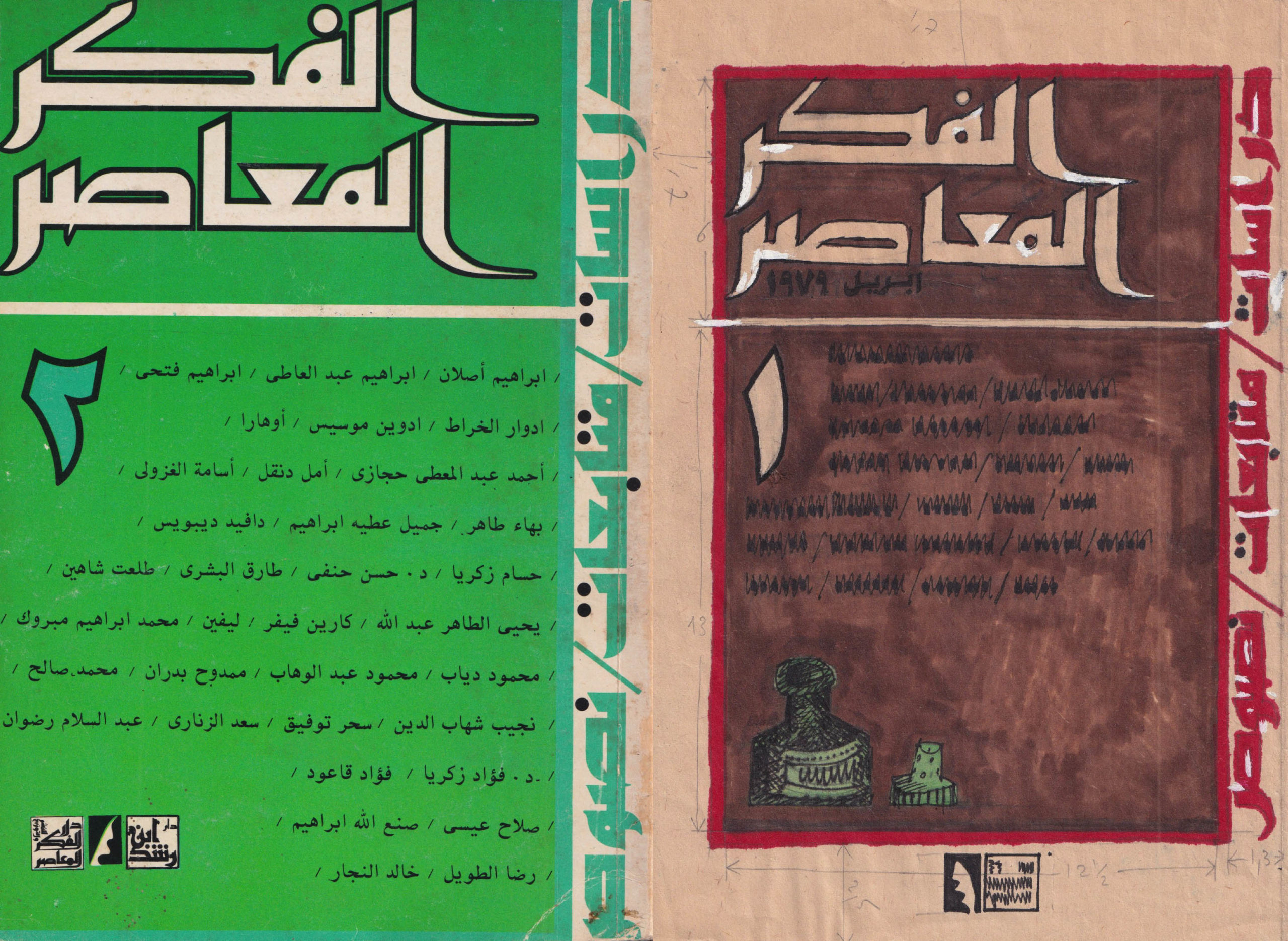

The accuracy of this statement in A History of Arab Design can be questioned when we read this ad for the Arab Graphic Centre, written on the back of the book Modern Thought, published by the Arab Graphic Centre, and whose cover was designed by Mohieddine Ellabbad. The ad makes no mention of the Arab Experimental Workshop for Children’s Books being a part of the centre or synonymous with it.

A History of Arab Graphic Design, much like the portal of the Academy of Fine Arts, claims to be an authority on the subject – its supposed legitimacy stemming from both its authors and the publishing institution – and presents this information as factual, even if it may not be. The relationship between the Arab Graphic Centre and the Arab Experimental Workshop for Children’s Books is uncertain, and the book ought to reflect this uncertainty.

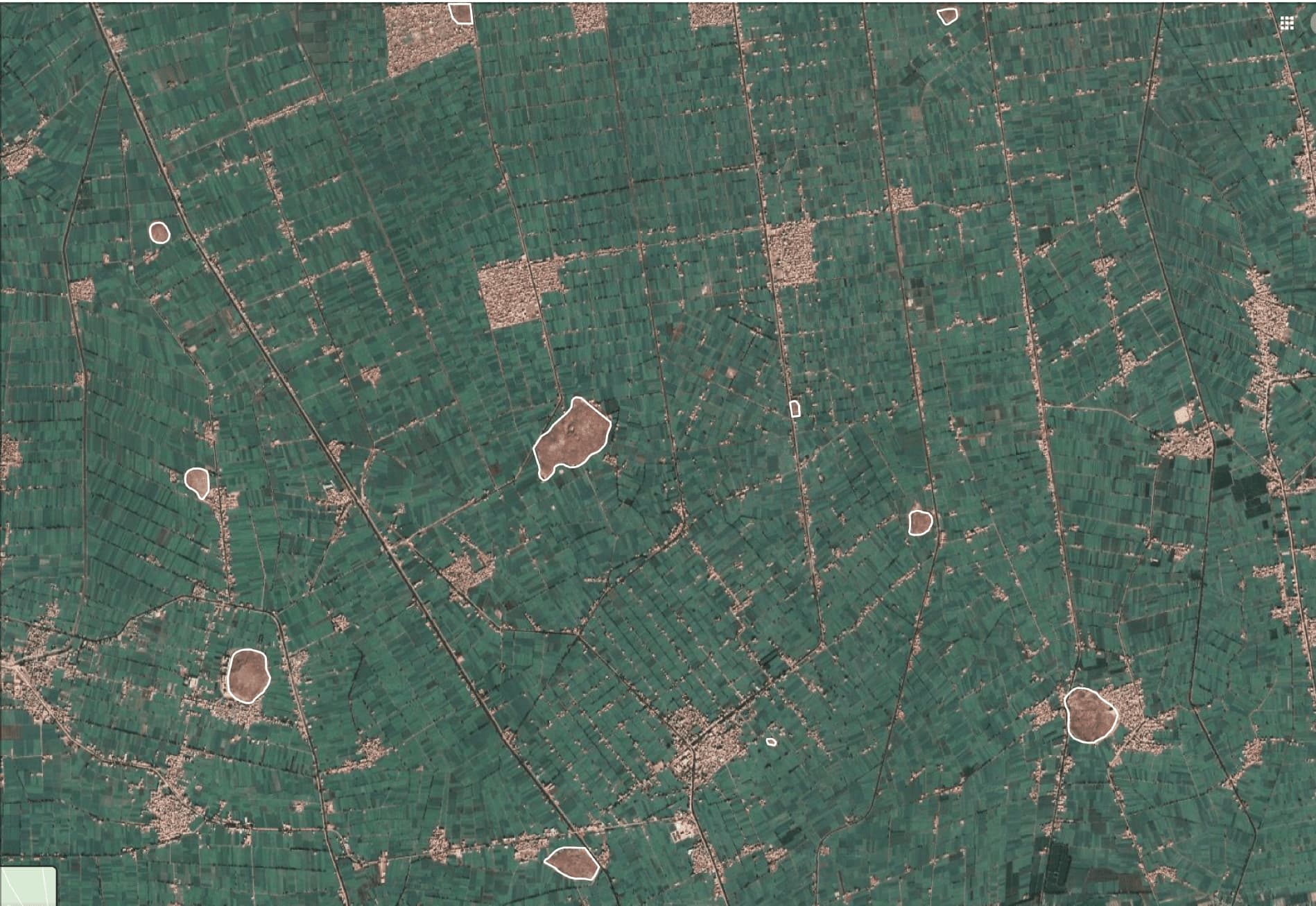

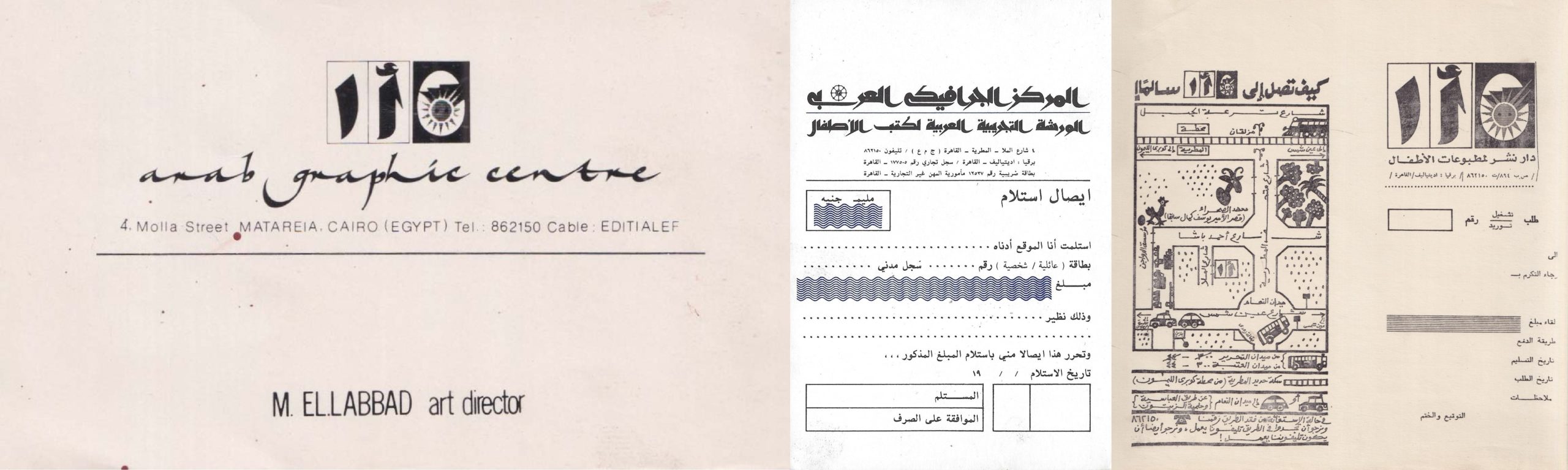

Some examples from the stationary coming out of both the Arab Graphic Centre and the Arab Experimental Workshop for Children’s Books help us speculate a few possible relationships between the two entities:

- The Arab Experimental Workshop for Children’s Books was a sub-entity under the Arab Graphic Centre.

- The Arab Graphic Centre and the Arab Experimental Workshop for Children’s Books were two separate entities headed by Mohieddine Ellabbad.

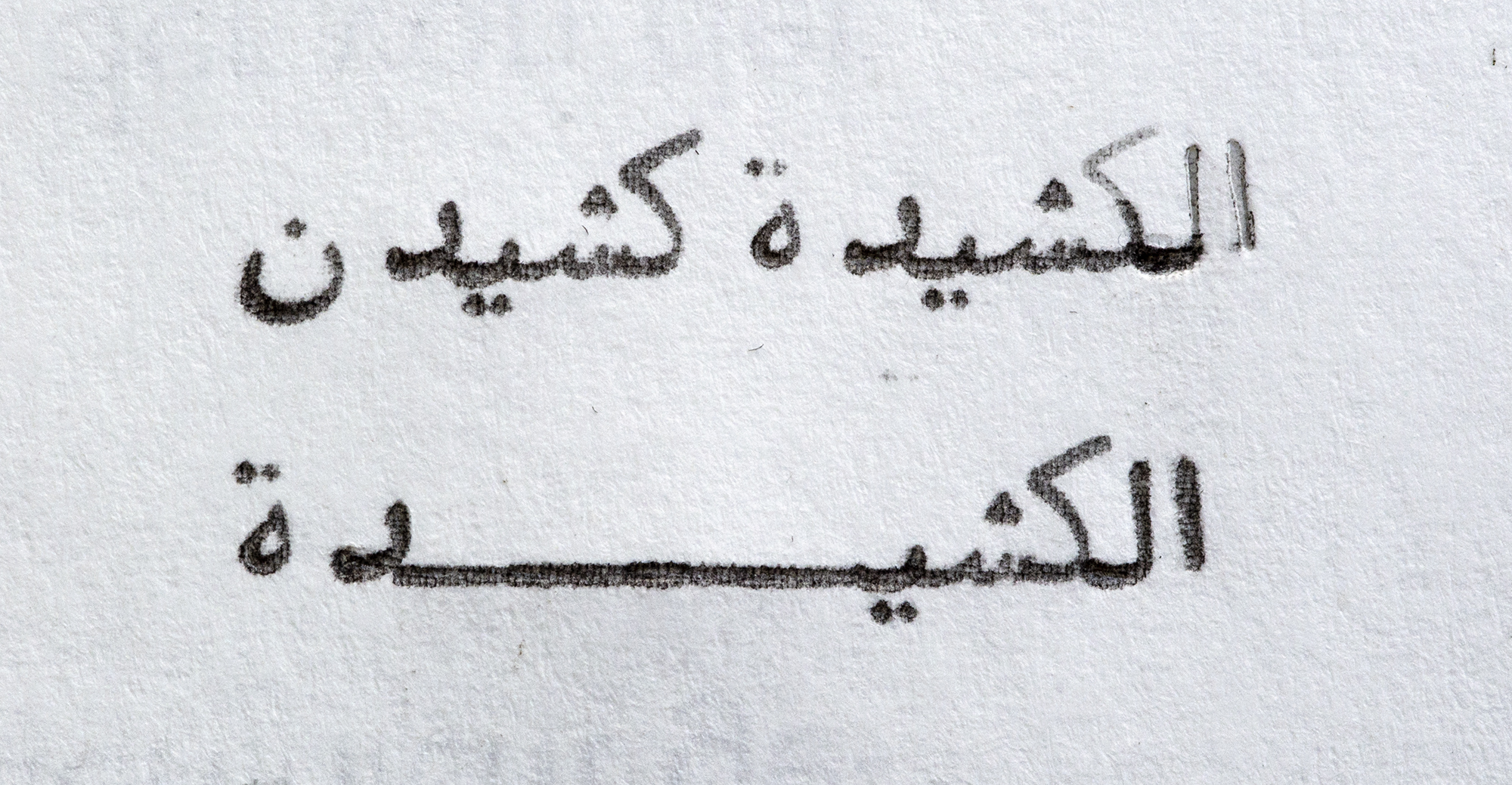

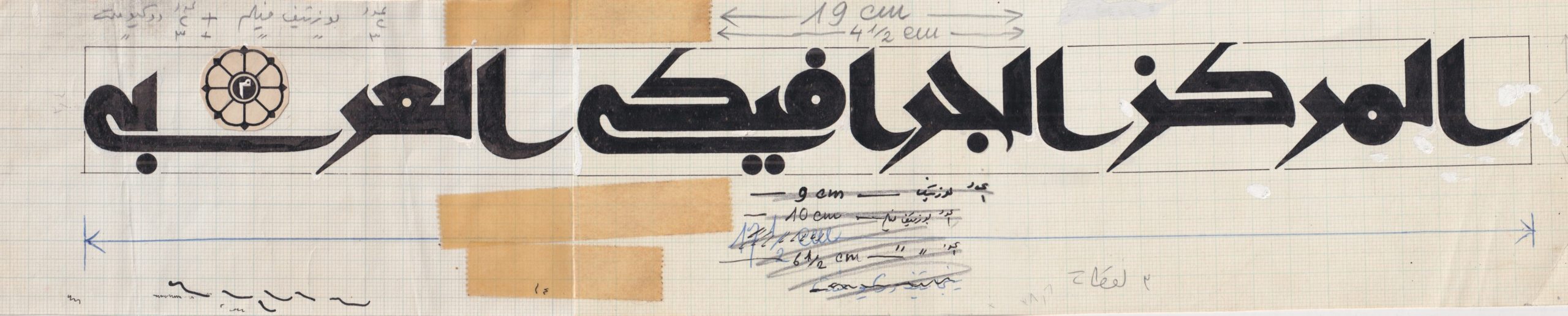

Indeed, they both shared the same space and were headed by Mohieddine Ellabbad, but that does not mean they were interchangeable entities. Looking at the stationery alone is not enough to identify a clear relationship between the two. If we consider size, scale, and typographic hierarchy – as an indication of the relationship between these two entities, then a close examination only leads to more ambiguity about the connection between the two. Perhaps Mohieddine Ellabbad himself had not established the exact distinction between the Arab Graphic Centre and the Arab Experimental Workshop for Children’s Books – we cannot know. Yet, the book presents this information with the definitive language of the certain.

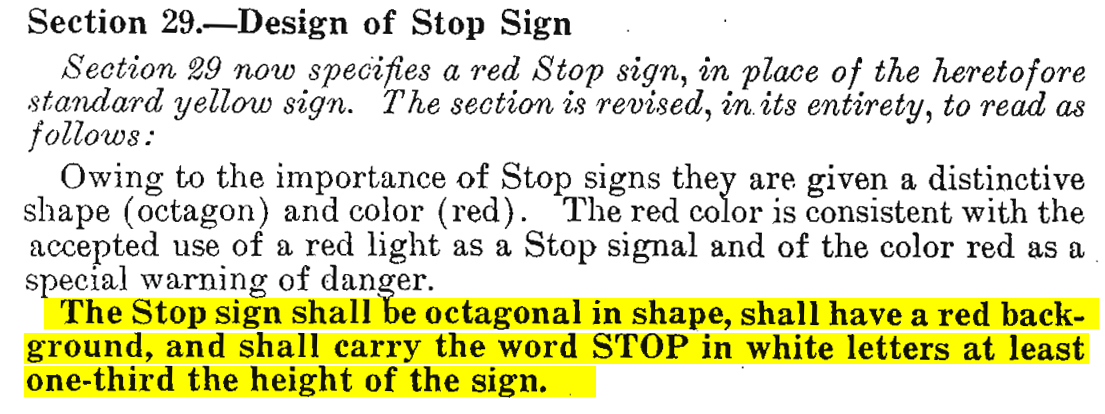

Another faux pas that the authors of the book make is that they erroneously refer to the Arab Graphic Centre as the “Graphic Center in Egypt.” Though an image of the AGC logo is indeed included, it is captioned “The Arab Graphic Center,” which is not how Mohieddine Ellabbad had chosen to spell it himself, opting instead for British spelling (Centre) in the logotype. We do not know why the book’s authors refer to the AGC by another name. It could either be an innocent oversight, or a conscious choice to be dismissive of this detail.

The rest of the entry in the book seems to reiterate things that are already available online in a number of different sources, and surely, such a book has to be reductive if each entry must be limited to 2-4 pages. Hopefully, this essay can help fill in this gap in later editions.

Another important resource for those who are interested is a dedicated section about Mohieddine Ellabbad in the magazine “The world of Books,” which features a few a few interesting reads, one of which is written by the Syrian Theater director, Osama Ghanam, and titled: “My name is Labbad: If drawing speaks.”

The present essay is and will remain a work in progress, through which I hope to reveal some of the nuances about someone who is akin to a mentor whom I never met. It could also be viewed as an exploration of an alternative kind of writing about design. Readers are advised to critically read this essay, and maybe use Khoi Vinh’s lens to view it.

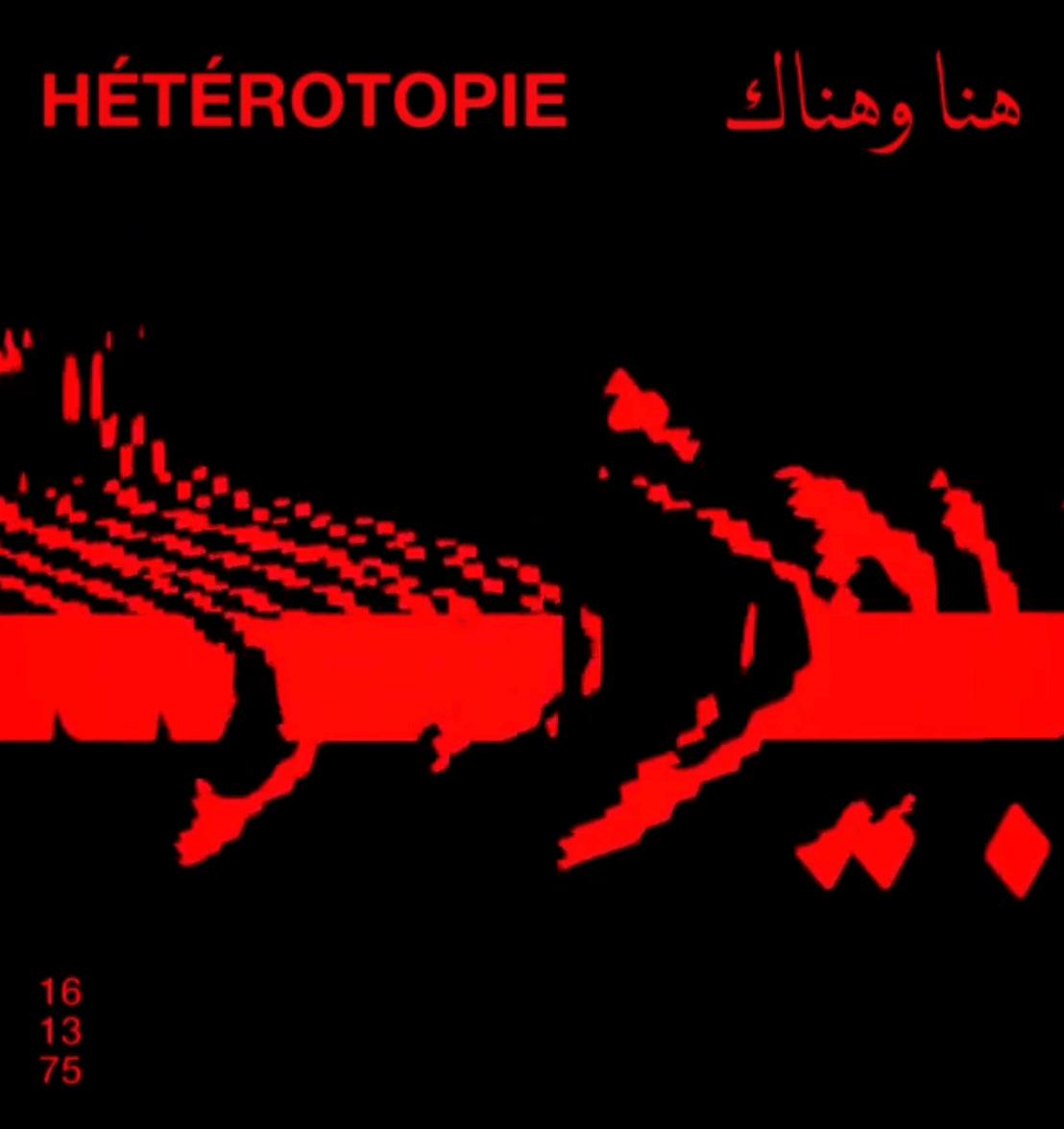

The Arab Graphic Centre (AGC):

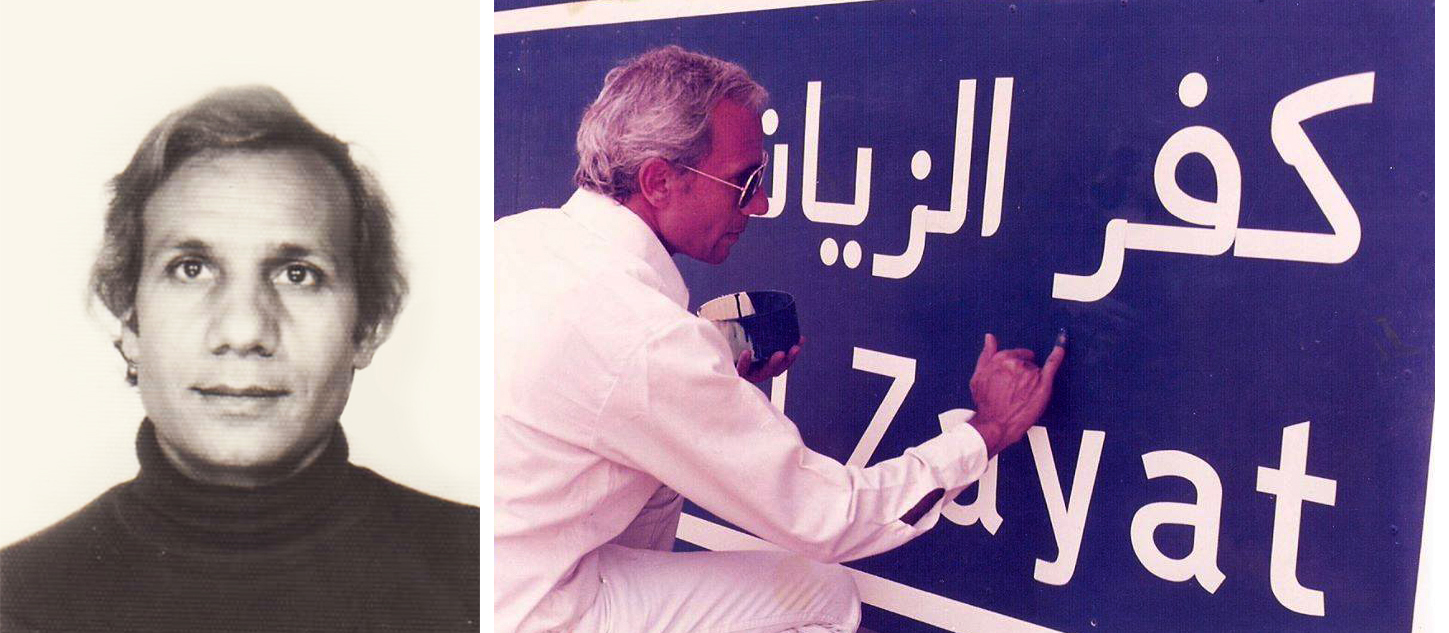

The Arab Graphic Centre was established in 1976 by Mohieddine Ellabbad when he returned from his journey with Dar Alfata Al Arabi in Beirut (1974-1976). Alongside the AGC, he also established the Arab Experimental Workshop for Children’s Books (A1), though the exact relationship between the two remains unclear. They both were located at 4 El Molla Street, Mataria, Cairo, Egypt. Mohieddine Ellabbad left Dar Alfata Al Arabi for various reasons, not least among them was the increasingly alarming danger of the Lebanese civil war[8]نص ملتقي شرم الشيخ. He and Nabil Shaath also had differing visions about the place’s future.[9]Khan. Revolution For Kids: Dar El Fata El Arabi, Recollected, 2010 He then returned to Cairo, ultimately establishing both the AGC and A1.

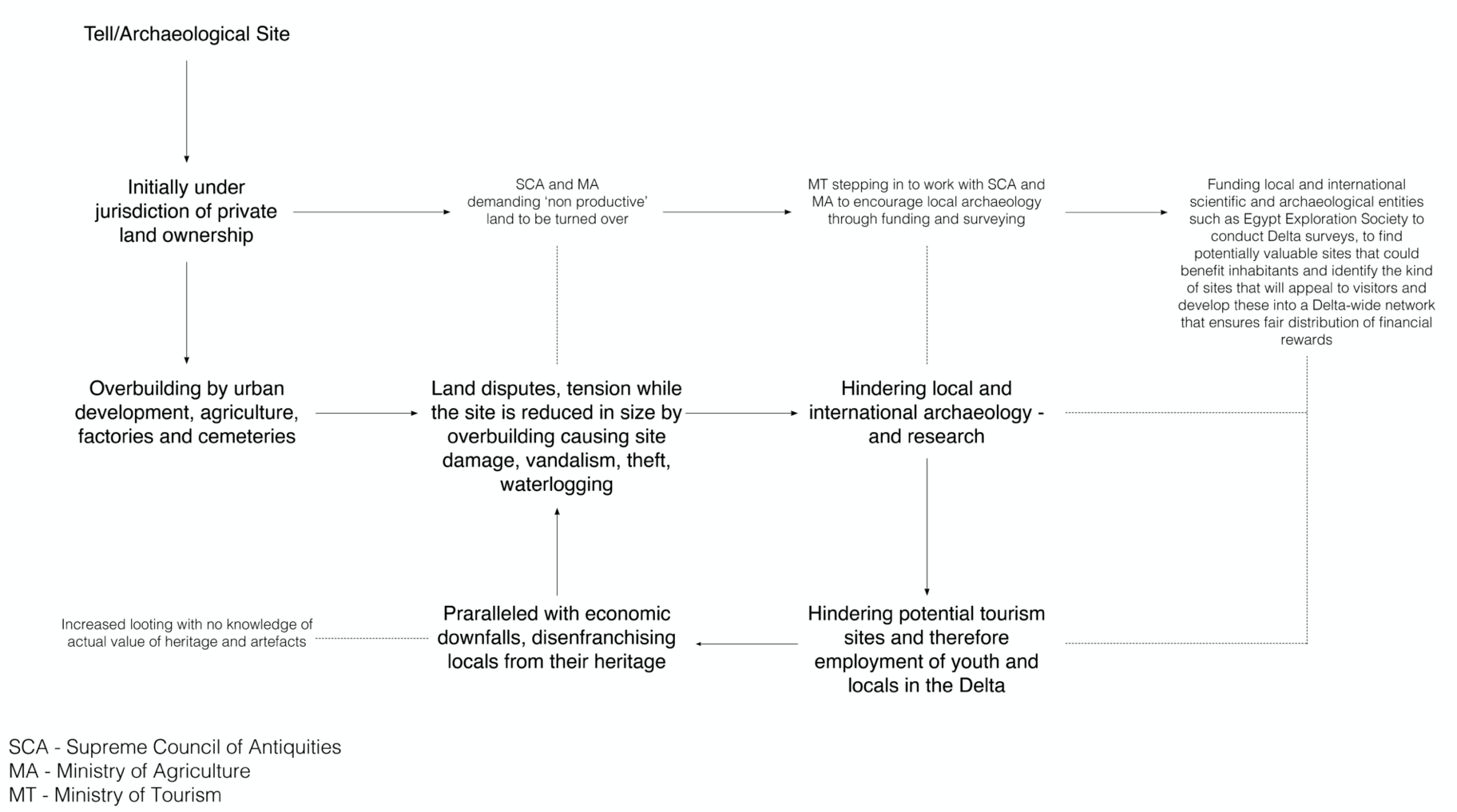

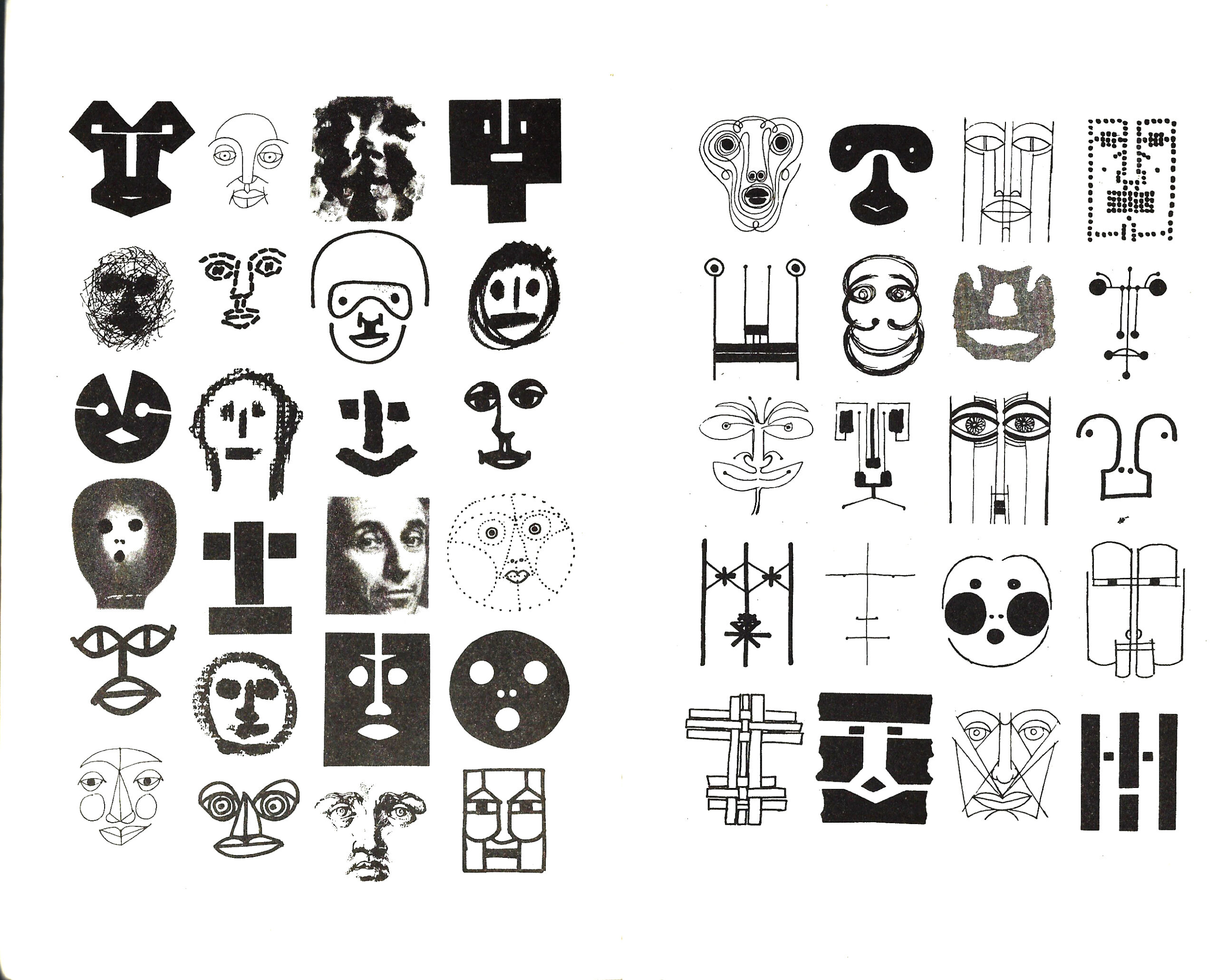

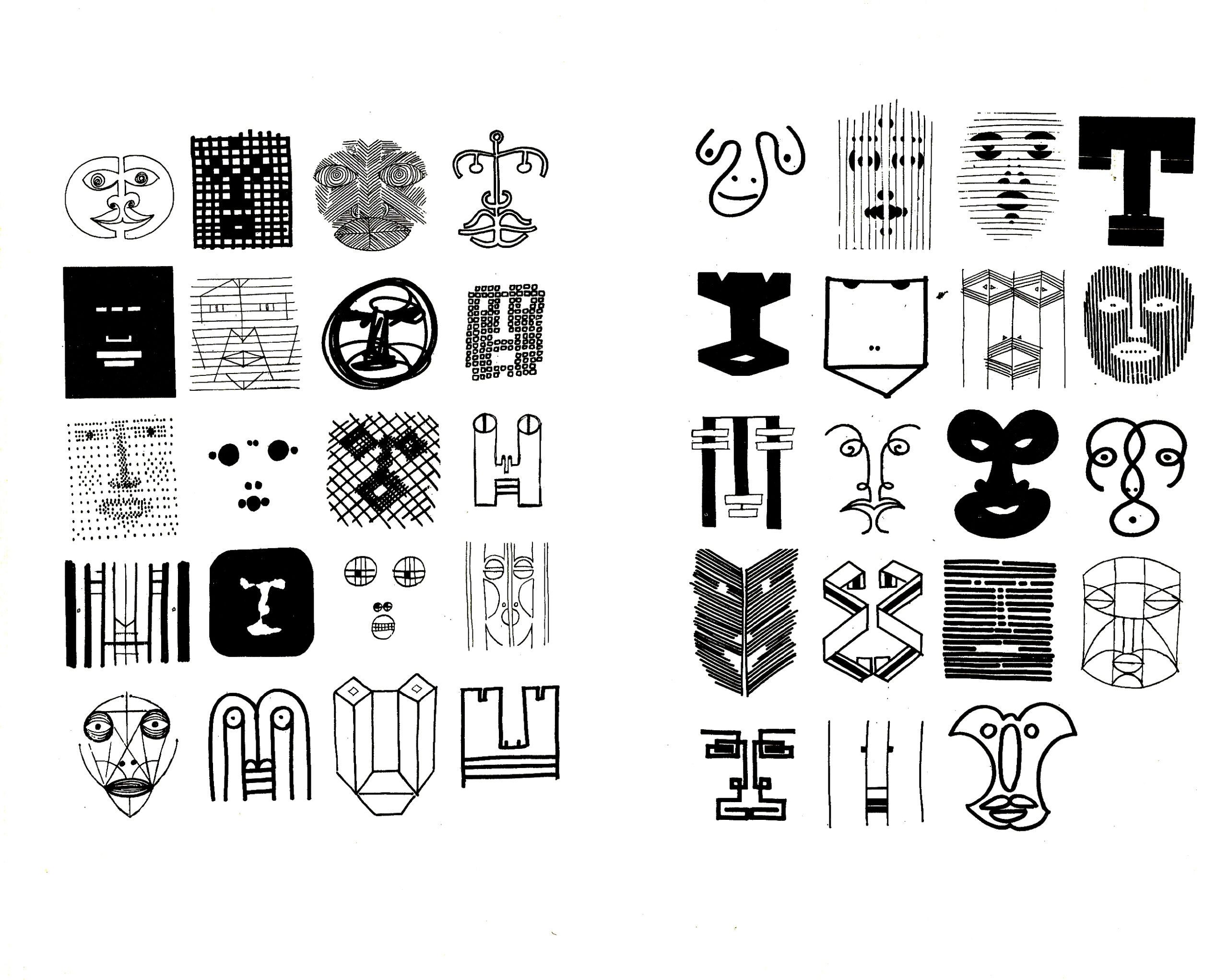

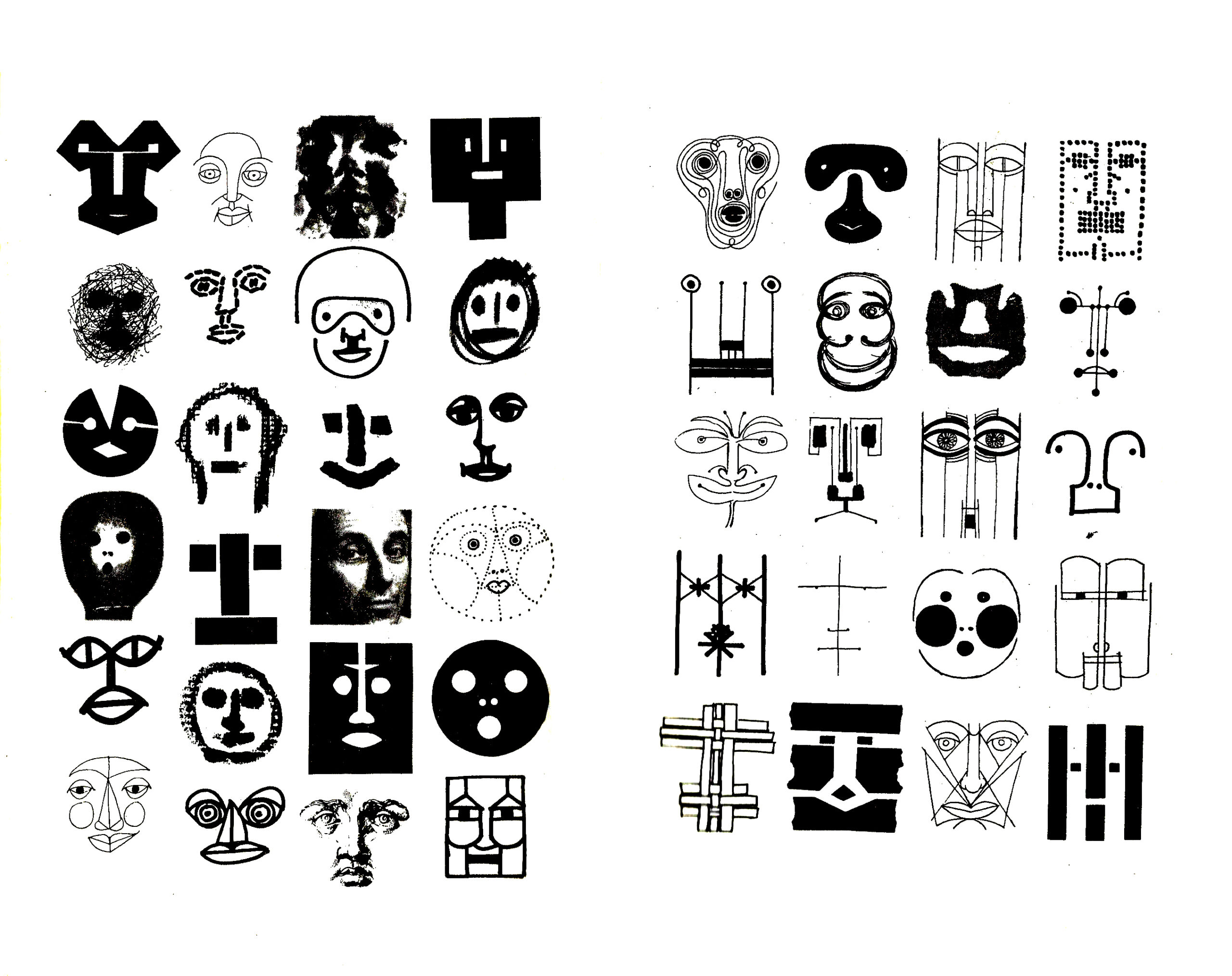

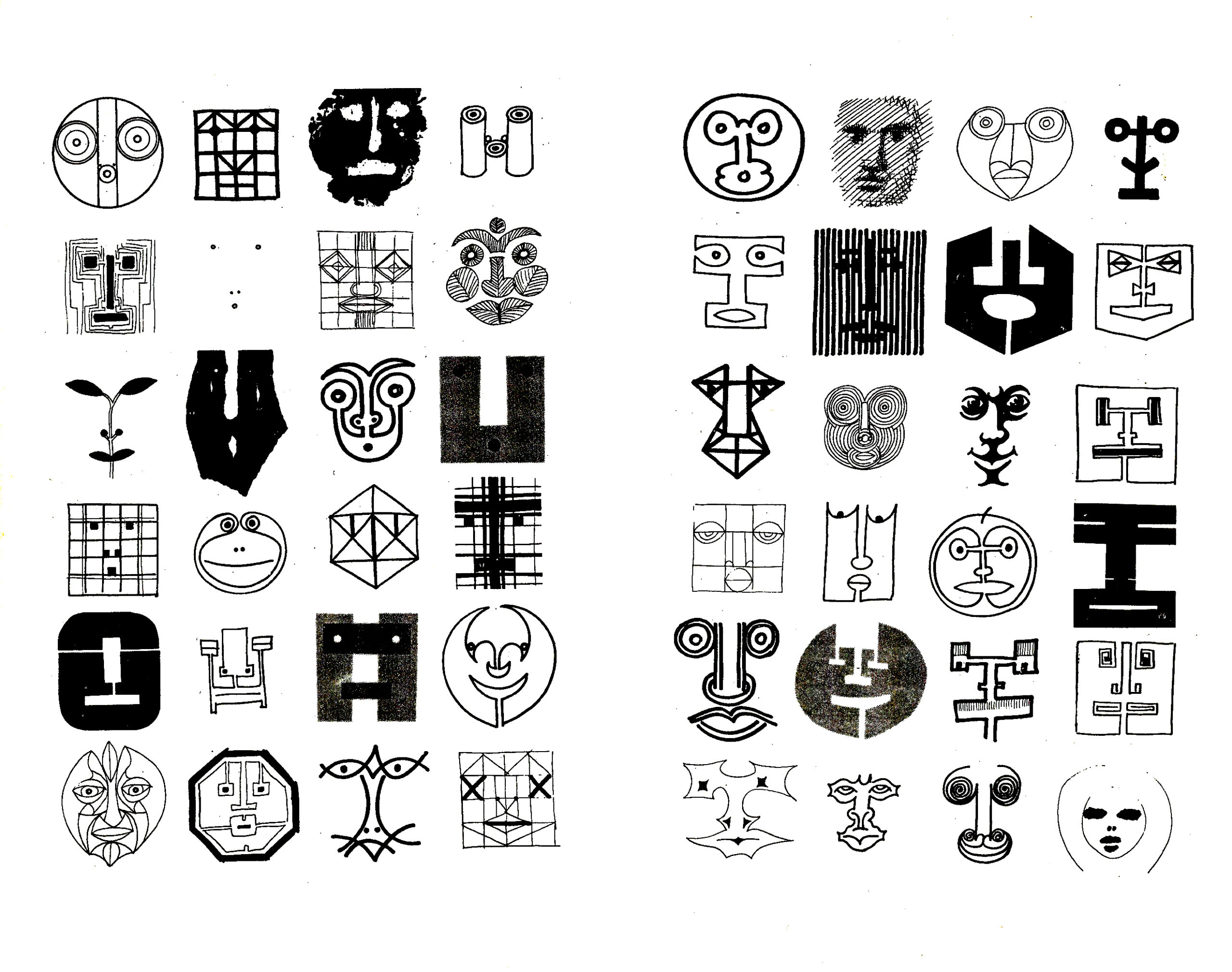

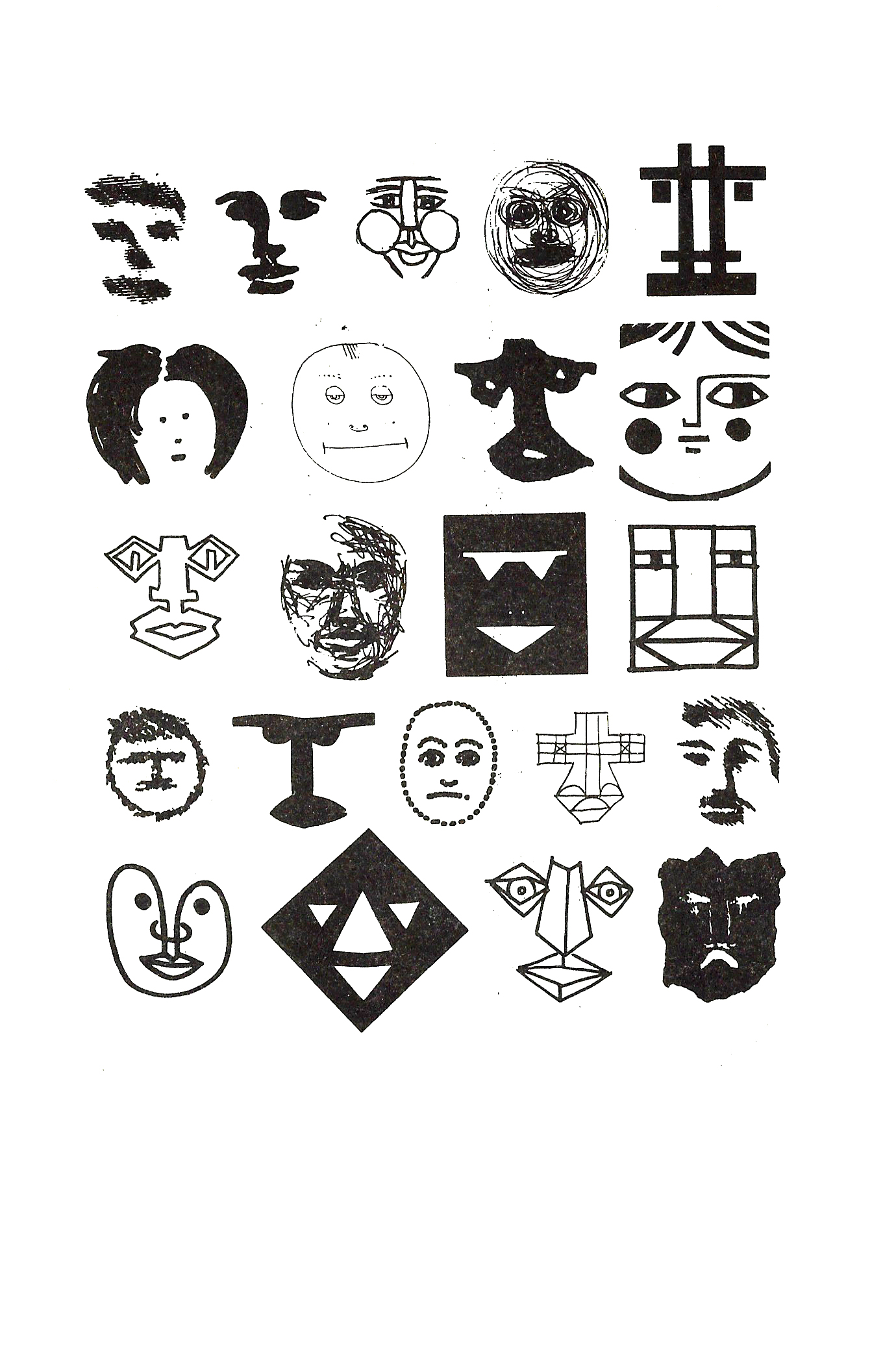

The centre aimed to establish an authentic modernist Arab graphic design practice, grappling with what was a pressing issue at the time: the relationship between tradition and modernity, or the double claim of authenticity and modernity (التراث والحداثة) through mass printed media. When he was asked in an interview with Salah Issa about the idea of authenticity in children’s books, his answer – that authenticity and modernity are one – captures his overall standpoint on the matter.

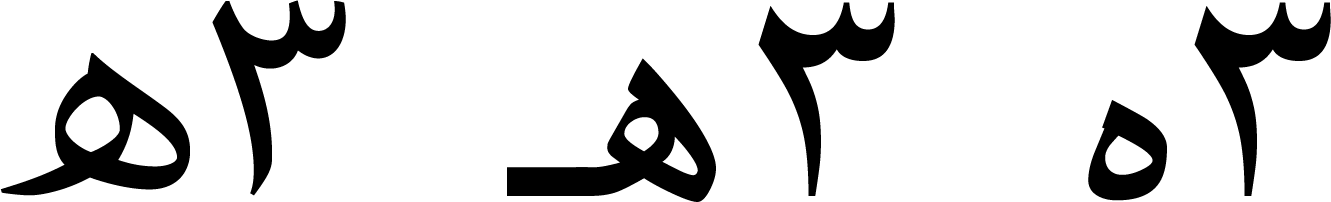

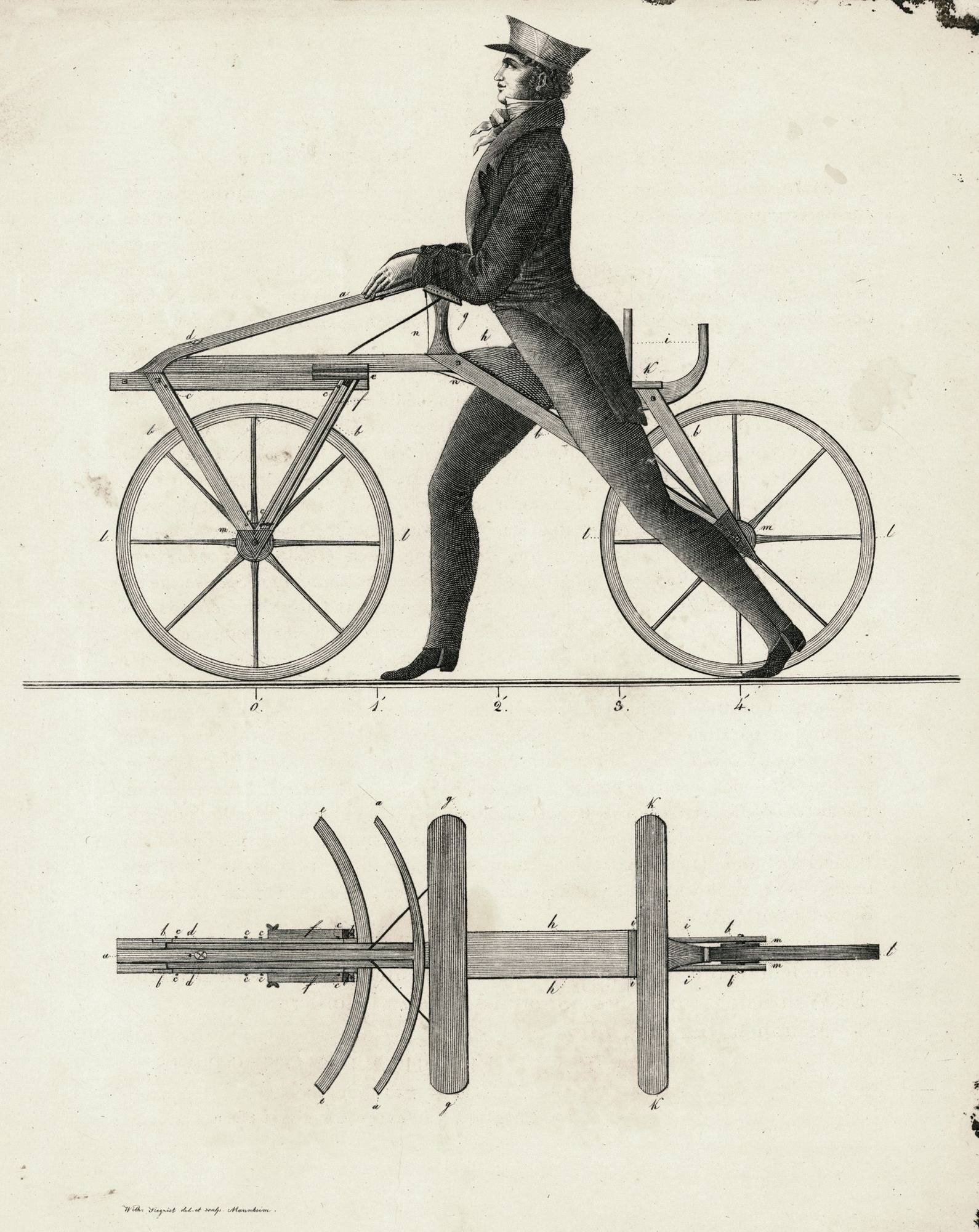

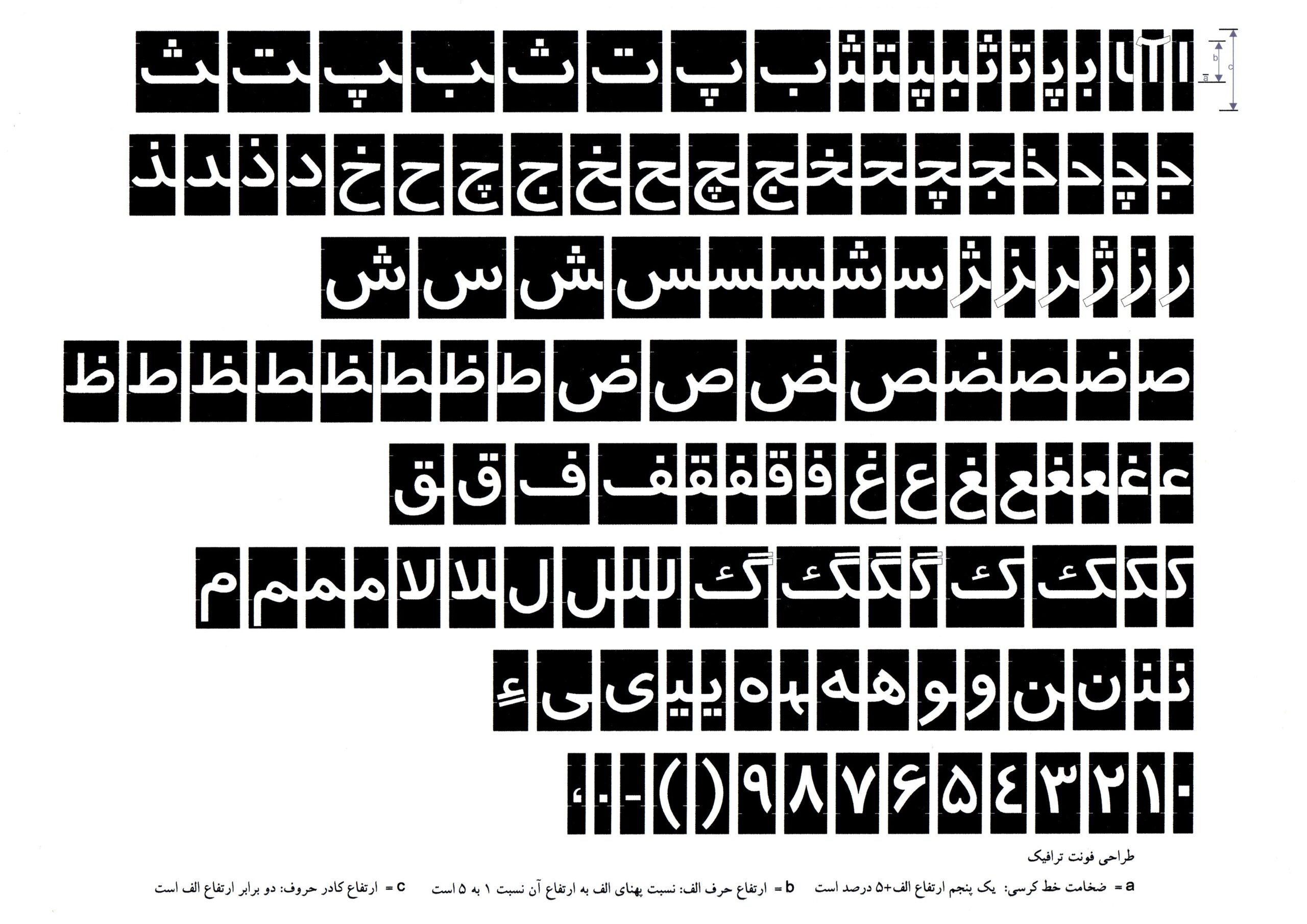

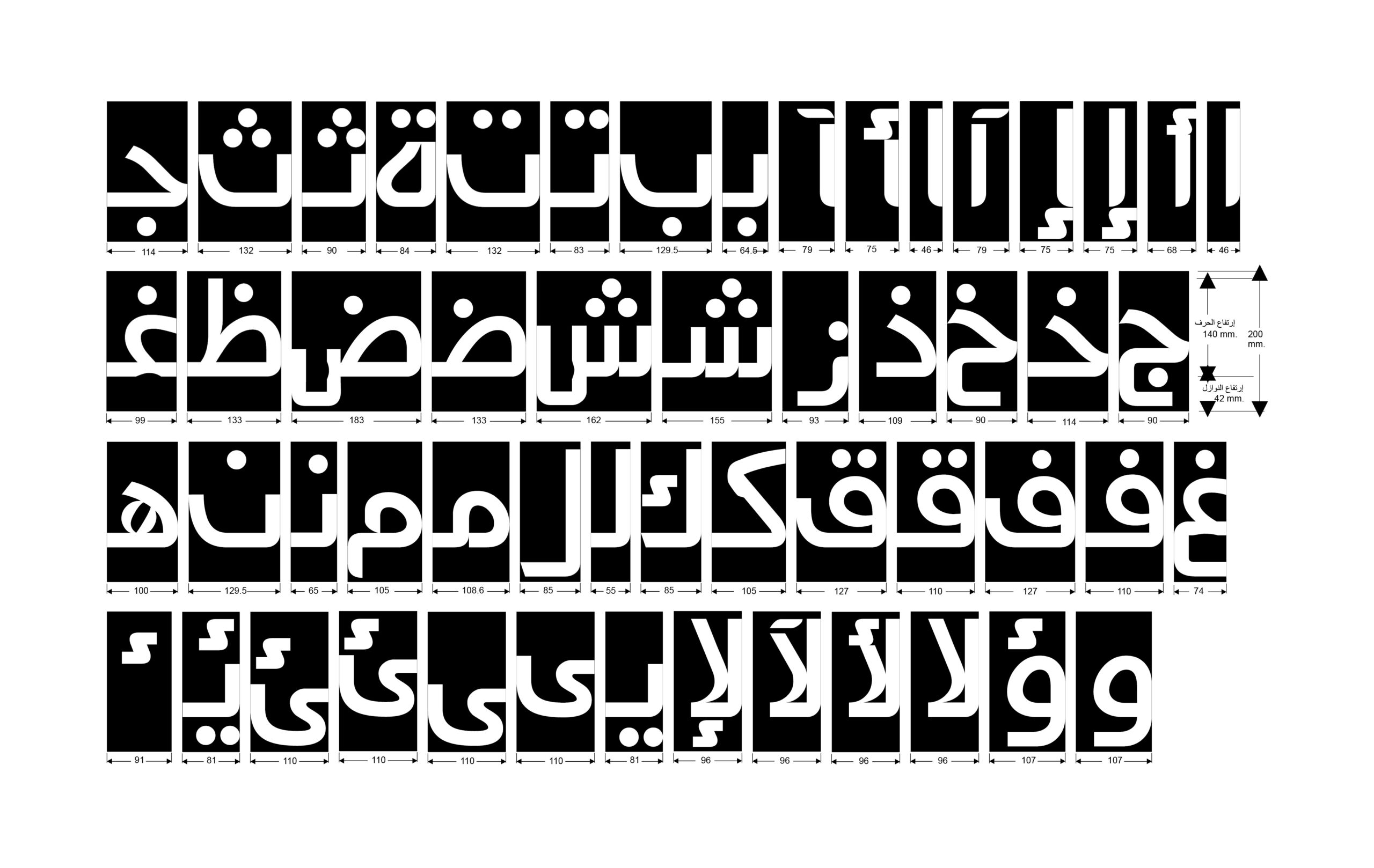

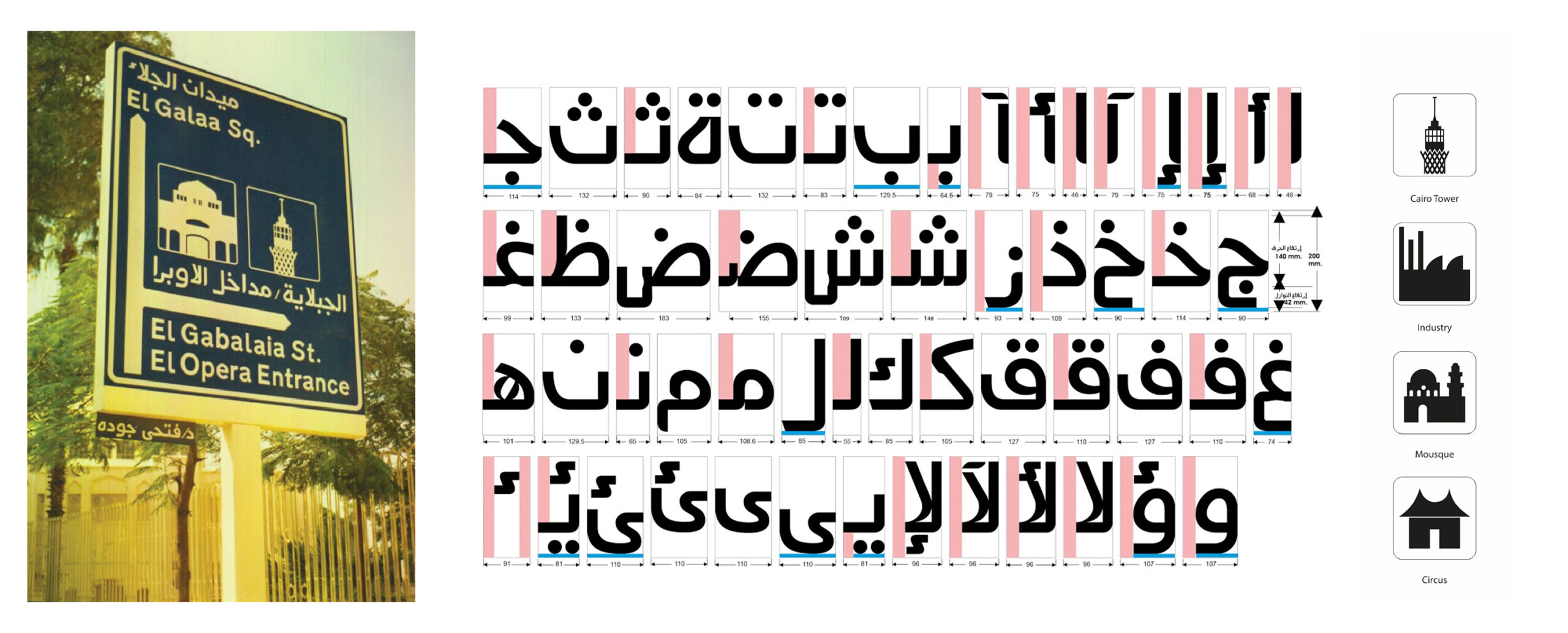

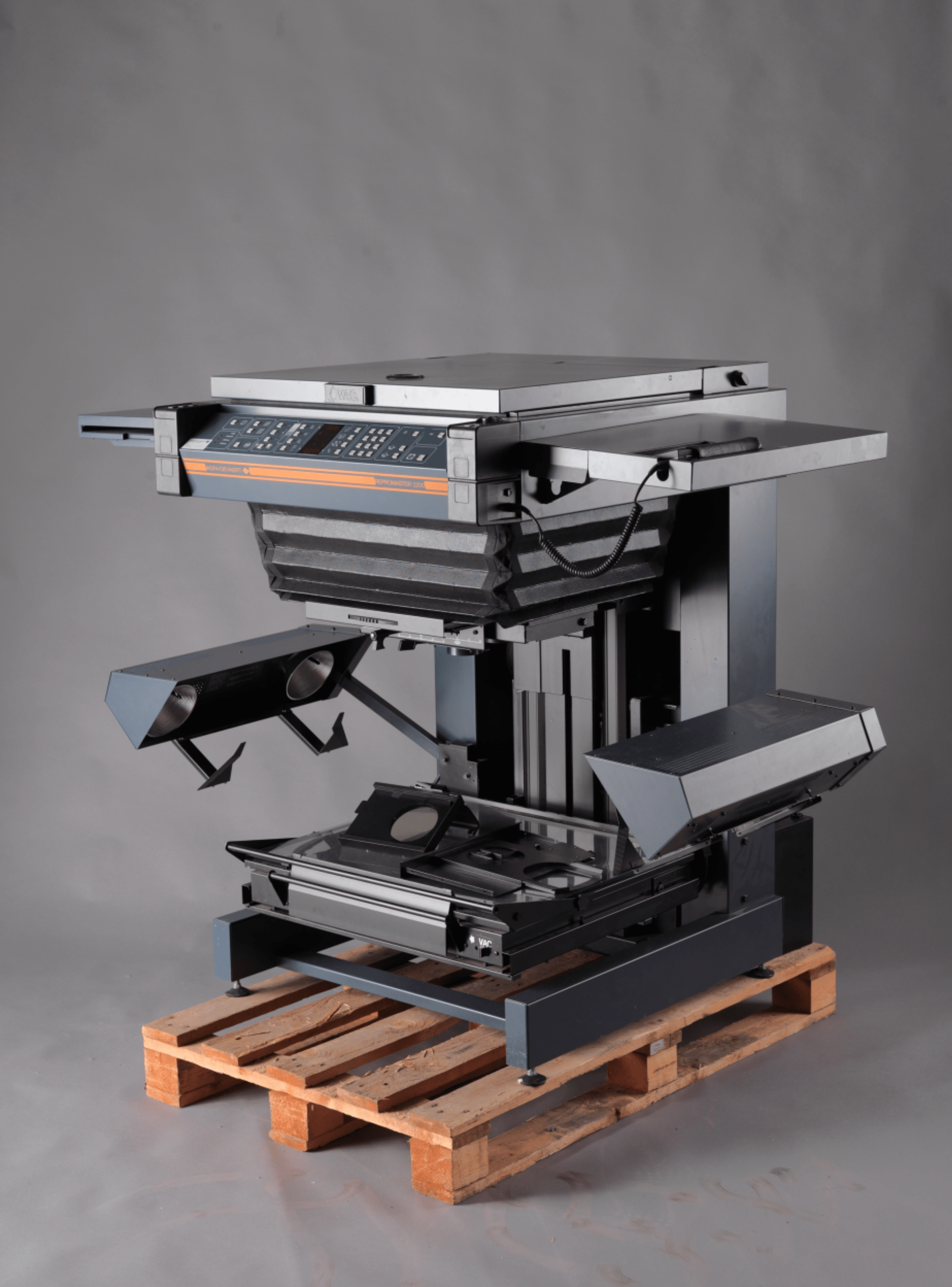

The AGC consisted of a small apartment in Mataraya, a very small space according to his son, Ahmed Ellabbad, who confirmed that Mohieddine turned it into his studio after the AGC was no longer operating. One of the rooms was designated for production, and had either an Afga Repromaster 3500 (see Fig. 1) or 2200, either one of these models or a similar one confirmed by both Ahmed Ellabbad and Moody Hakim, an old colleague of Mohieddine Ellabbad’s. The machine is a photomechanical transfer, also known as PMT. It offered a multiplicity of functions, including photolitho for special effects and other prepress functions.

Mohieddine Ellabbad equipped the machine with Japanese made layers (contact films) of filters, which were used to emulate what we now know as photo filters or effects in Photoshop. These filters created halftone effects, circles, color overlays, mezzotint, and more. Both the machine and the films were a significant investment, but for him it was an inevitability if he wanted to succeed in having ultimate control over the design process, as well as present the AGC as a true collaborative space. This machine was accessible to anyone who needed it away from the complexities and bureaucracy of publishing institutions, which were the sole provider of such a service at the time. He created a catalogue with samples of these effects, which were used to showcase the possibilities that can be achieved through the machine. He also presented it to clients to display its technical capacities, and distributed it to other graphic design practitioners who wanted to use the machine or know more about it.

The history of prepress (design before the computer) in the region remains a mystery to us to this day, as there is very little documentation of this period about the design, printing, or publishing process with its technical aspects and practices.

At the time, this machine was considered to be an advanced machinery which required special technical competence. A few years prior, Mohieddine Ellabbad had met the Ethiopian-Italian print specialist known as Mr. Louigy through Ros Alyousef. Mr. Louigy came to work in Egypt and was praised for being meticulous in his work, a trait that he shared with Mohieddine Ellabbad, and which also explains why they gravitated towards one another. Mr. Louigy played an important role as a technical consultant for the AGC. Mohieddine Ellabbad took his advice on which machine was better and then got a Danish-made photo transfer machine. Soon after, Mohieddine Ellabbad asked Mr. Louigy to be in charge of running the machine at the AGC on a project basis. Eventually, Mr. Louigy trained a person who would be permanently located at the centre to handle the machine to facilitate the day-to-day workflow.

This ensured that almost all prepress work happened in-house which, to a great extent, guaranteed the reduction of any mistakes that could happen in the process, and that the work would directly go from the AGC to the client.

The AGC aimed to be both an experimental and practical space for the design practice. According to Nabil Tag, who joined the AGC in 1977 as a permanent designer and Illustrator, the centre also engaged with client briefs and projects, providing services such as brand identity, editorial design, brochures, flyers, and posters.

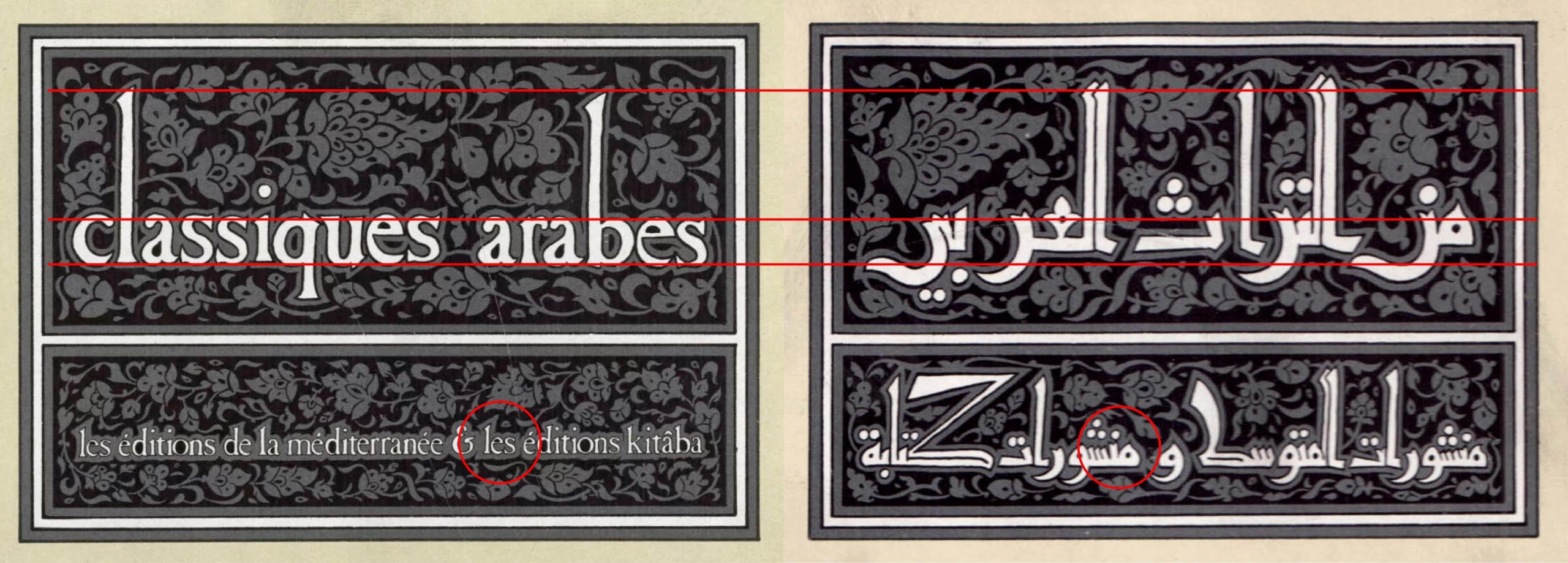

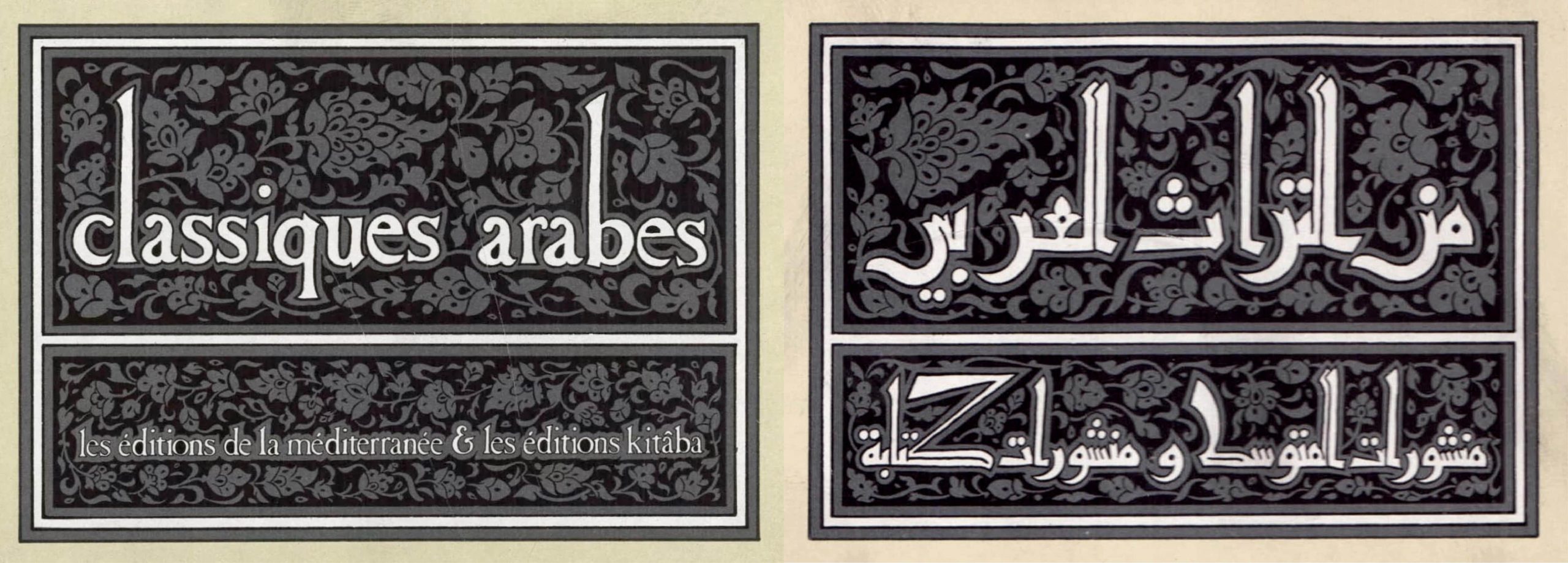

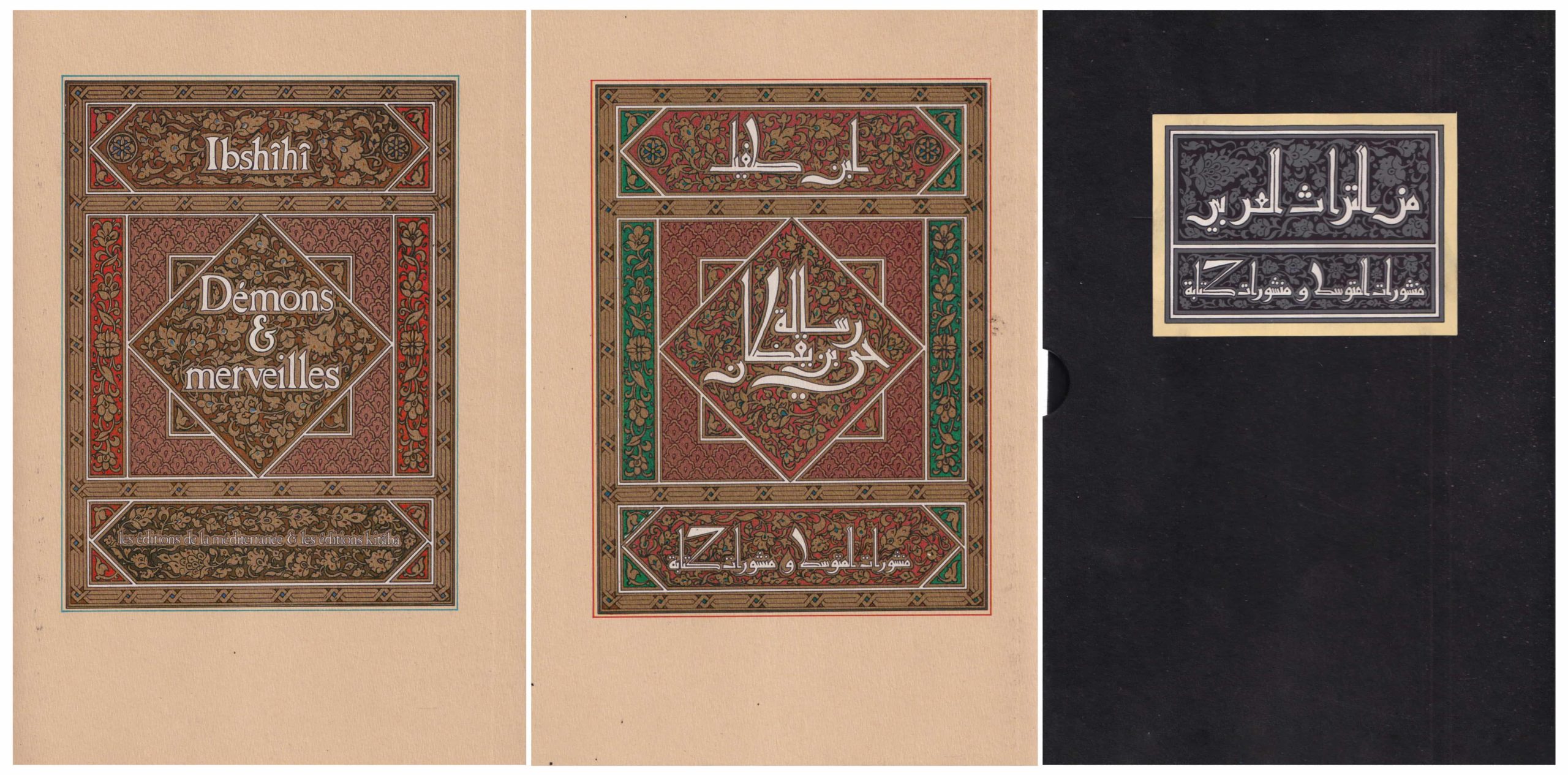

When asking both Ahmed Ellabbad and Nabil Tag to identify one of the most important projects undertaken by the AGC, they both agreed that it was what Mohieddine Ellabbad jokingly referred to as the “Black Box” project: a limited-edition series of classical Islamic works published in 7 volumes, that features the works of people such as Ibn Fadlan, Ibn Hazm, and Ibn Khaldun. The series was published in 1981 by Les Éditions Kitaba & Les Éditions Kitab. One can try to reconstruct the thinking process of the AGC from the clarity of direction in the outcome. The AGC attempted to explore the possibility of infusing something traditional with a sense of contemporariness. However, it shows that it was not intended for it to be an equal balance between those two ingredients, as the AGC vigorously favored the traditional side – with good reason.

The 7 books are nested in a cardboard black box with a sticker on it that features the name of the series and publisher, written in a meticulously-crafted variation of Eastern Kufic script. Both the title and publisher’s name sit inside a rectangular compartment. When juxtaposing both the Arabic and French versions, we can see that Mohieddine used an all-lowercase serif typeface for the Latin, while making sure that some distinct features from the Kufic script spill over the the Latin script. This can be observed in the extended stems of the “l” and the “b,” where they are forcefully stretched to match the height of the Alef Lam in the Arabic, a feature that is unique to this kind of Kufic. We can also notice that some counters in the Latin are almost closed to match those in the Arabic. This may initially appear to be nothing more than a graphic treatment for consistency, but this deliberate design decision carries a more radical underpinning. The reversal of influence between the Arabic and Latin in the script echoes a much deeper decolonization project that Mohieddine Ellabbad was adopting.

This decolonization project was the substrate upon which all of Mohieddine Ellabbad’s work sits. Only when we consider the totality of his body of work, we can discern the thread weaving through this project. We could attempt to analyze one piece he did that couldn’t be more straightforward and emblematic of this project.

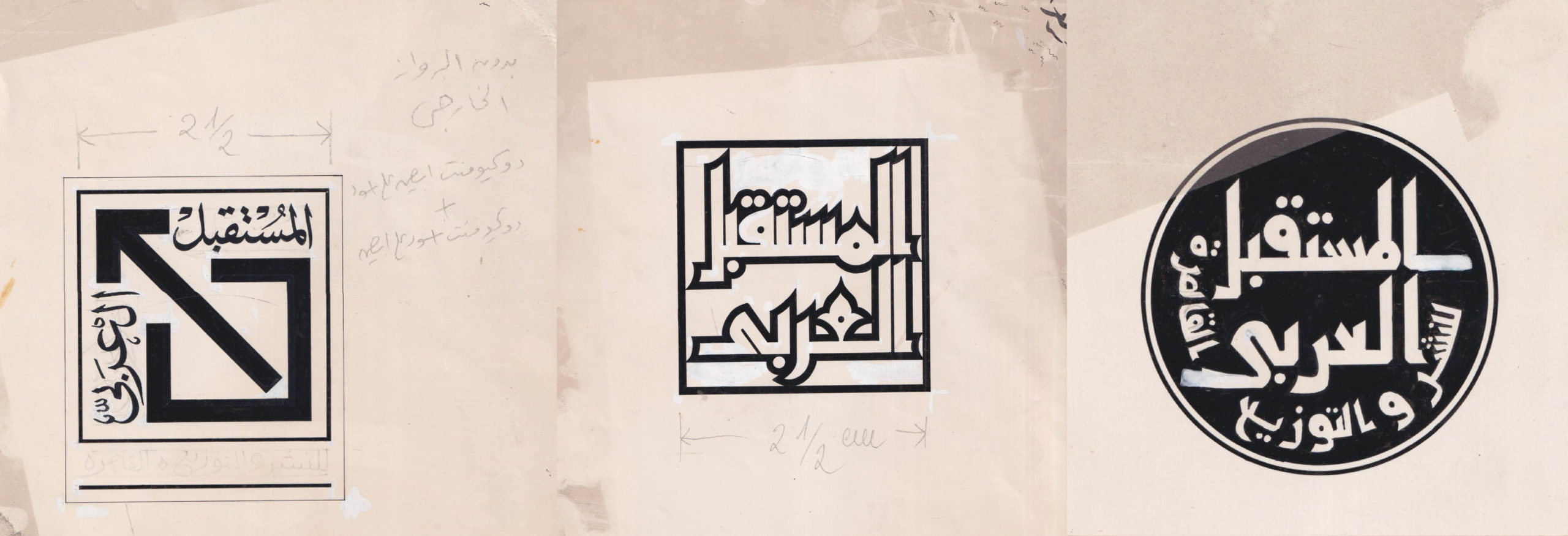

Logo design for the publishing house “The Arab Future.”

Here, we see the evolution of the design of the logo, the iteration on the left being the final one. The logo has both a linguistic message and a symbolic one. The linguistic message only requires a knowledge of the Arabic language to comprehend. However, the symbolic one seems to have a multitude of meanings. The signs included here are a broken square – which implies that there square was once whole – with an arrow coming out of it. For the sake of understanding the meaning of this symbol, if it is captured in motion, then there must have been a starting point. Let us try to imagine this starting point (see animation below).

The initial state of this symbol would have been a closed square, with a diagonal line dividing it into two equal spaces. The enclosed square may suggest a hegemonic space. When this is thought of as a simplification of a much larger structure, one could claim that it could represent the (Euro-American) hegemony that Arab intellectuals were trying to break from. Then we have the arrow that breaks out of the square. The arrow is a universal sign for moving, force, and direction. The arrow moves from right to left, emulating the Arabic writing direction as it breaks out from the square. Then the linguistic message of “The Arab Future” is attached by means of alignment to the head of the arrow, where the force is condensed. It could then be read as: The future of Arabs lies beyond the Euro-American cultural imperial project.

There is more than one reading that can be drawn from this symbol, but this will suffice to illustrate how this decolonization project found itself in a different avenue.

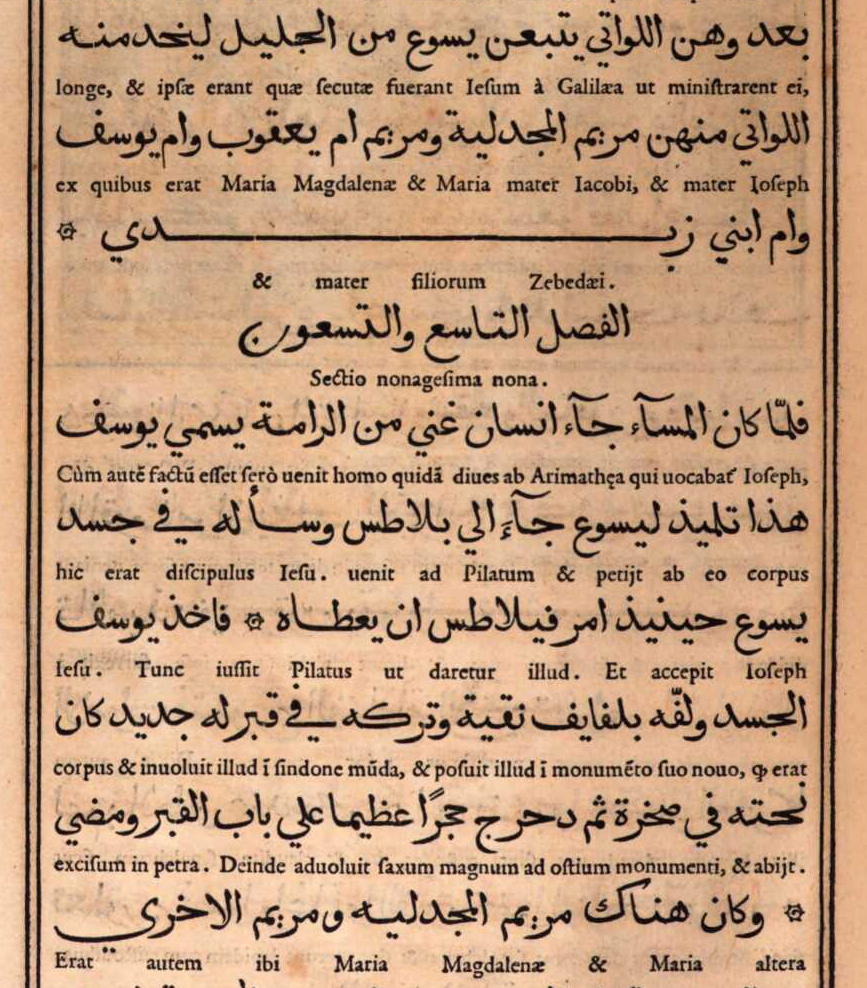

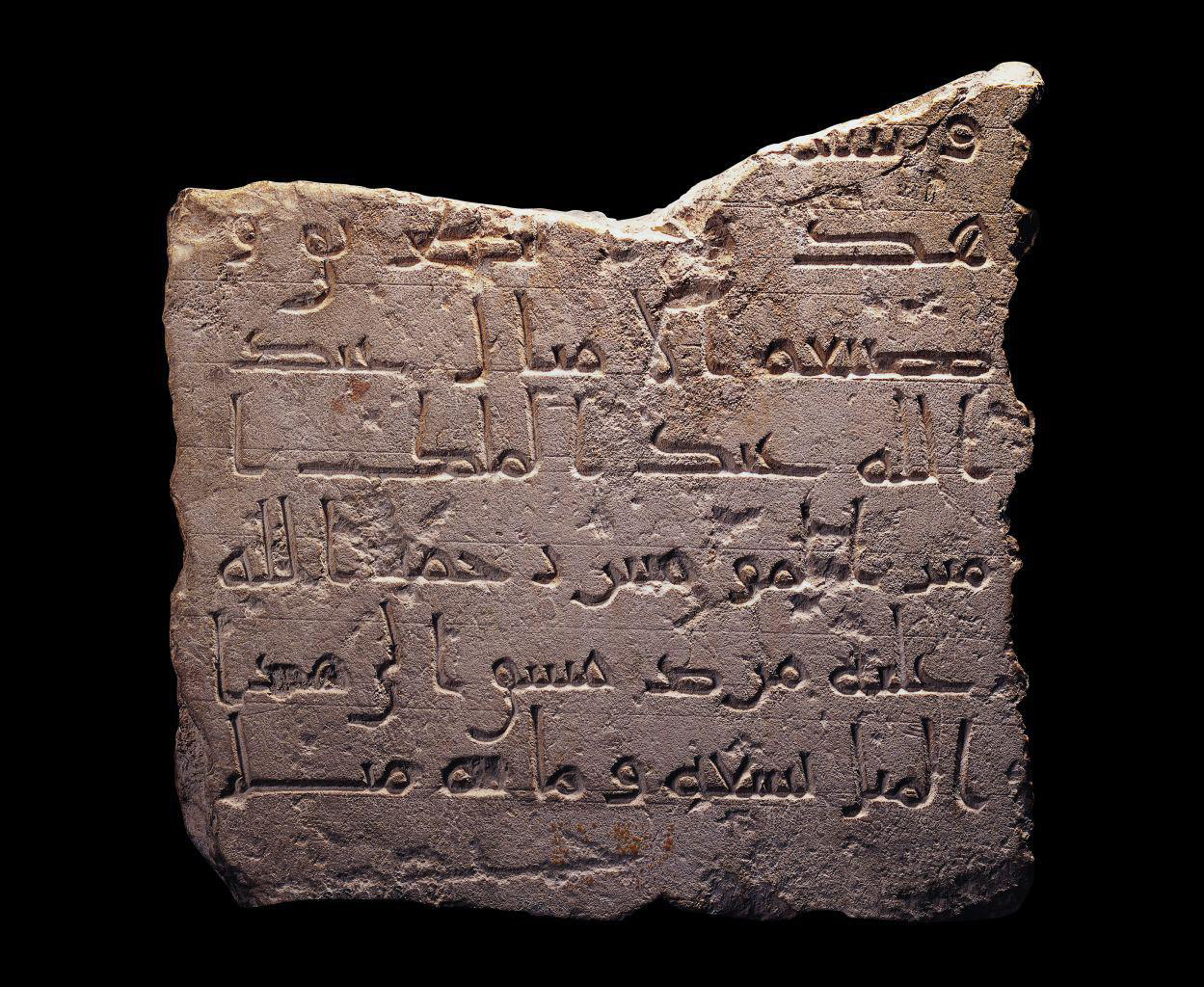

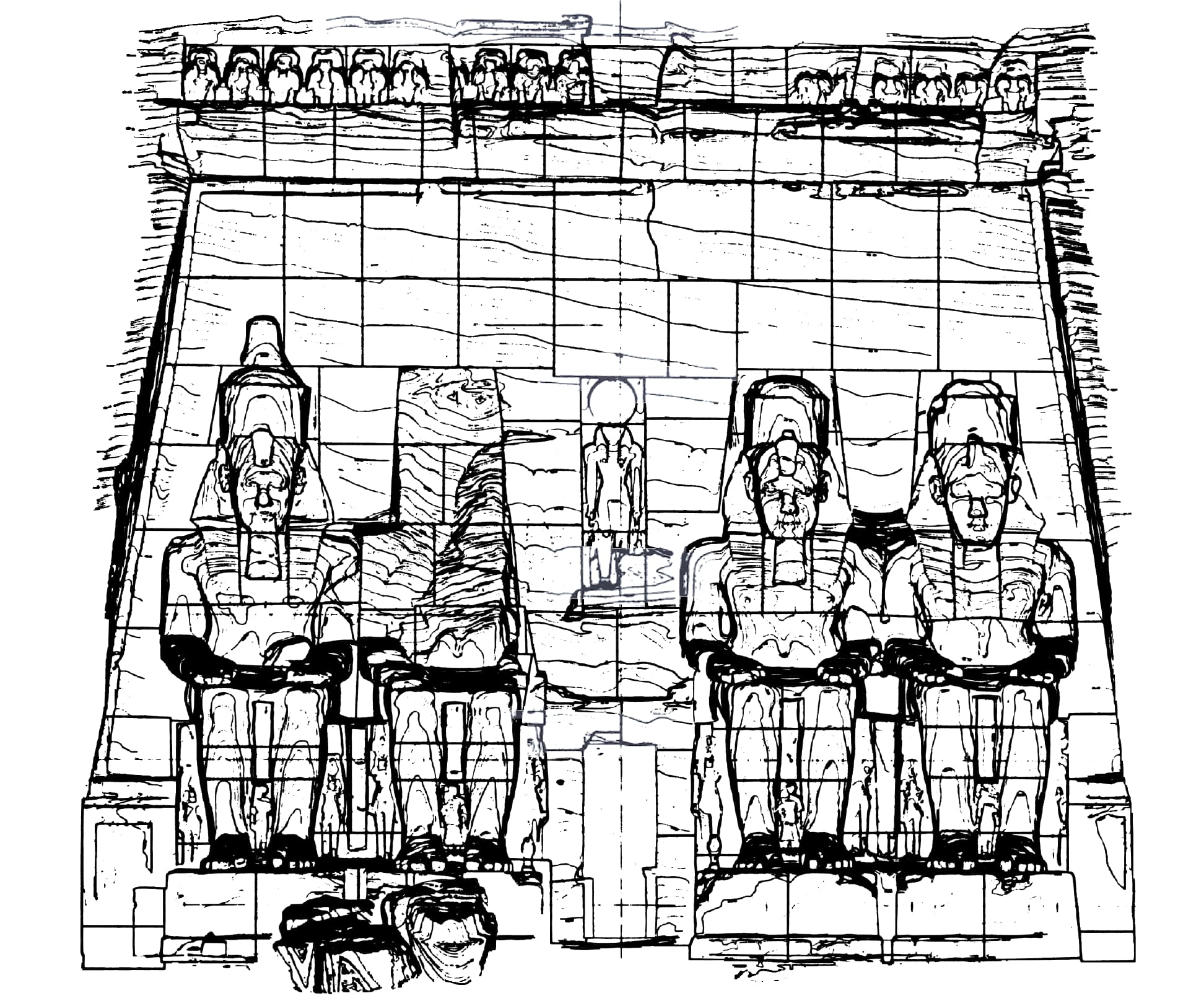

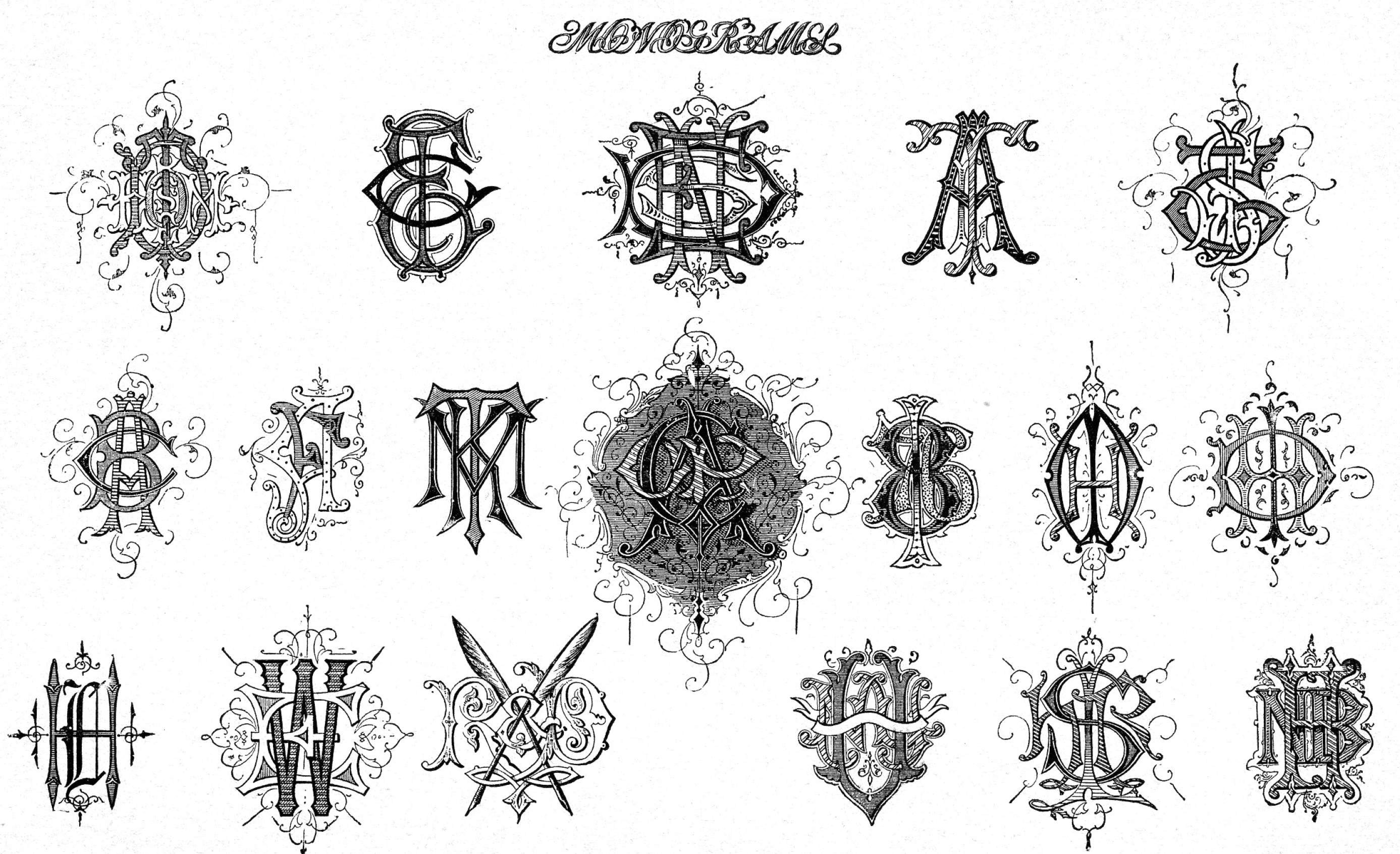

Back to the blackbox project: we see behind the titles what seems to be a variation of a Mamluk-inspired floral ornament. This book series was specifically inspired from Islamic manuscript traditions, which Mohieddine Ellabbad was particularly interested in, believing them to contain a wealth of graphic practices related to book-making which, for him, corresponded to what an Arab design might start from.

From the obvious cover design of these books to the subtler traditions like Khatm (colophon), Tatmim (closing formulae), a form of Isnad (ascription), and unwaan (title page)[10]Gacek. Arabic Manuscripts, 2009, he researched Islamic Manuscript traditions extensively. According to Ahmed Ellabbad:

“He had a wealth of references from different libraries to study, the likes of the Vatican, Italy and The National Library, France. He used to be always curious to look for their original copies and buy the slides when possible.”

The layout, ornament and script style has staggering similarity with this Mamluk manuscript from Egypt. One might assume it could have been one of his many references while working on this project.

Mohieddine Ellabbad was not only interested in exploring these traditions for his own practice, for he was first and foremost a design populist, seeking to introduce the public to these traditions. He refused the notion of belittling the public’s ability to apprehend sophisticated visual communication, and he saw that this perception of the viewers lowers the standards of the profession.

Among his attempts to bring attention to these manuscript traditions was through A1.

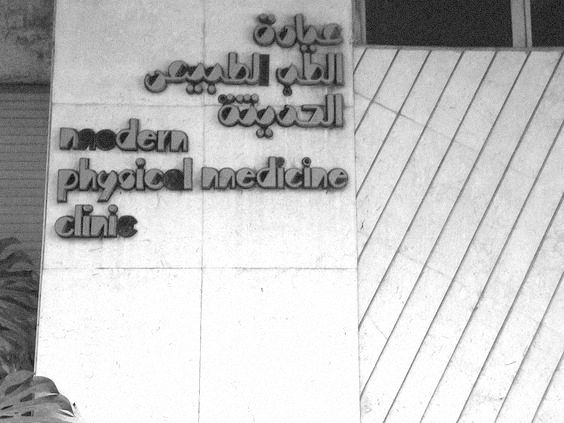

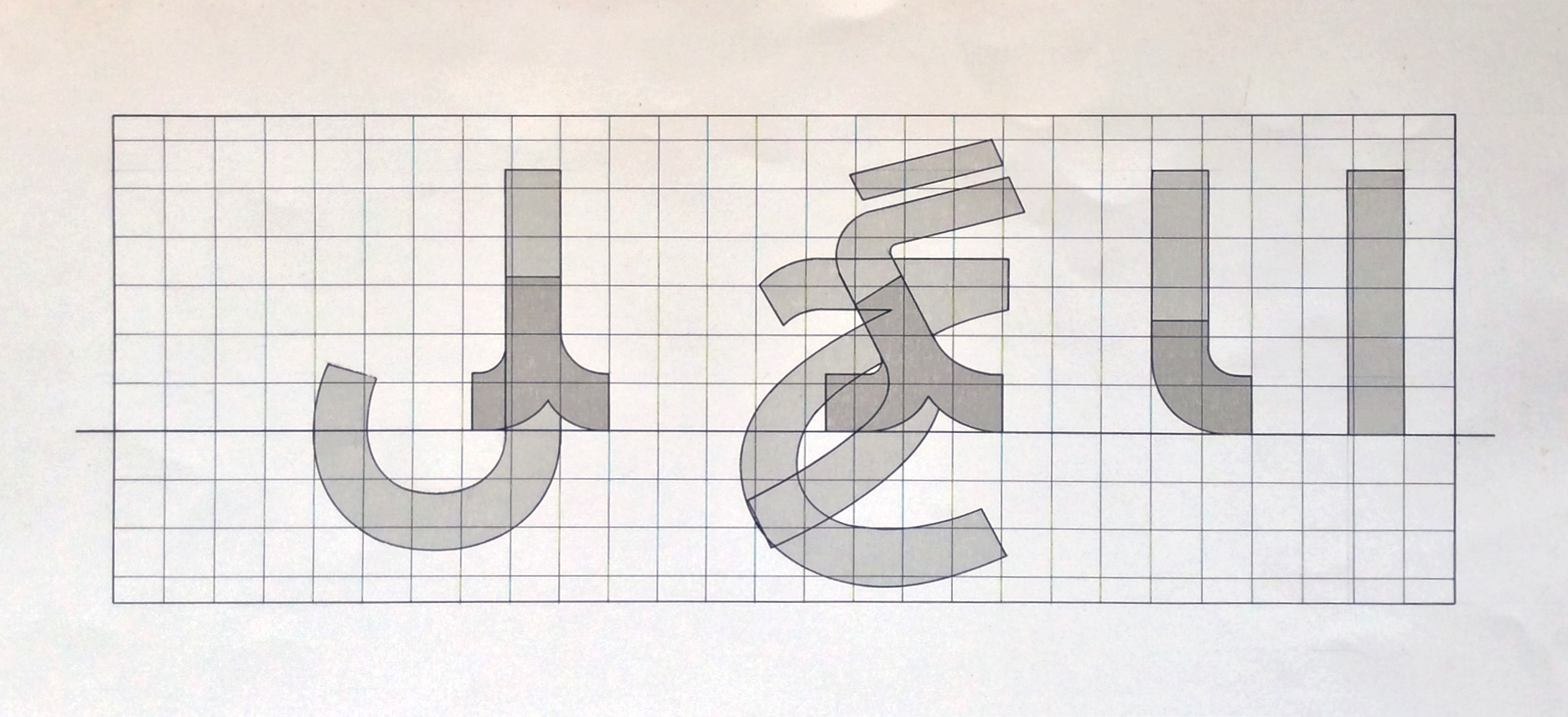

The Latin logo of the center is itself a statement of and on this approach. Subverting the foundation of the Latin written word, Mohieddine Ellabbad reinforces the Arabic reed pen to write the Latin logo, and to suppress the Latin characters by imposing the Arab characteristics onto it. The result is an “Arab Graphic Centre” that is Arabized.

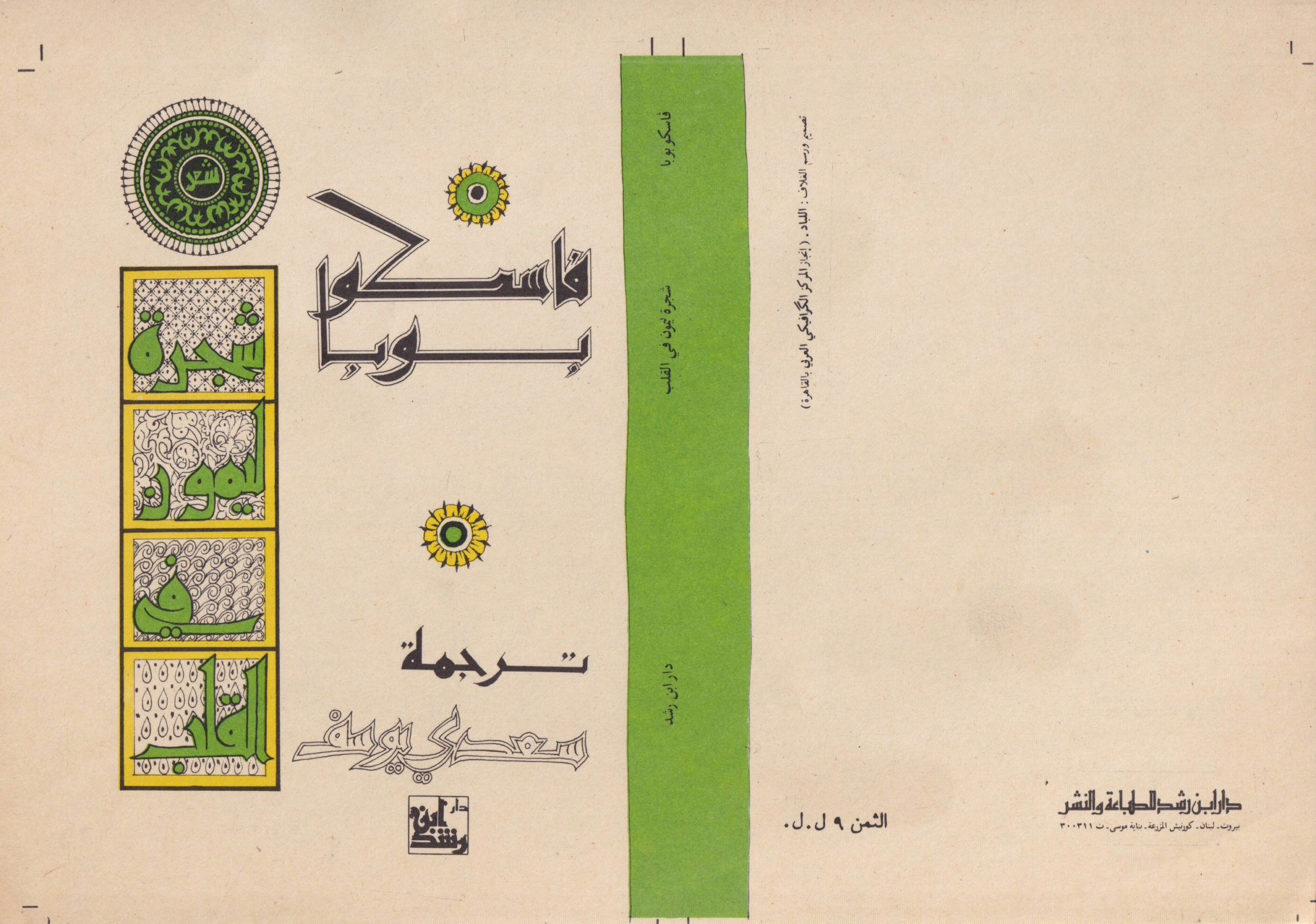

This inspiration can be detected across his practice, with many different experimental and practical works that attempt to start from these traditions, incorporating them when possible. One example is a series of books published by Dar Ibn Rushd in 1981. In this series, Mohieddine Ellabbad experiments with the visual vocabulary of Islamic manuscripts. He skillfully uses decorative elements and visual devices not only for aesthetic purposes, but also to guide the viewer through the design, emphasizing certain parts by placing them in medallions. We can also see the utilization of the “circular medallion,” known as the Shamsah element, as a text divider between the author’s name and other pieces of information.

The Shamsah element was commonly seen in illuminated Quranic manuscripts as verse-counting devices, verse-markers, or verse-ending markers. Their highly decorative botanical shapes were meant to force the reader to take a pause at the end of each verse, as well as a reminder of the point that the reader reached in the text.

This shows that Mohieddine was knowledgeable with the function of these elements in their original context, which requires extensive research and study. Moreover, the liberty in positioning the design elements and their proximity, orientation, and placement in some of the covers, challenges the idea of an authoritative understructure grid perpetuated by the Swiss style of design, which had a significant influence on the Western modernist movement. Rather, he chooses to free some elements from this grid, which creates organic- looking designs.

My investigation into the AGC is still undergoing, and this essay will be followed by as many more texts as needed to shed light on the Arab Graphic Centre and its founder Mohieddine Ellabbad.

Resources to consider for Arabic design writings:

- The Arabic Design Library: Here

- On Arabic Justification: Here and Here

- Safar Magazine: Here

- Cosmopolitan Radicalism: Here

- Signs of Conflict: Here

- A History of Arab Graphic Design: Here

- Arabic Type-Making in the Machine Age: Here

- Arabic Typography History and Practice: Here

- Arabic Typography: Here

- The Abbasid Tradition: Here

- Qur’ans of the Umayyads: Here

- Arabic Manuscript: Here

Special Thanks to the following people:

1. Mr. Ahmed Ellabbad

2. Mr. Mimi Bisher

3. Mr. Mohsen Refaat

4. Mr. Moody Hakim

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Teal Triggs, Graphic Design History: Past, Present, and Future |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑3 | Ibid |

| ↑4 | Blauvelt. Designer Finds History, Publishes Book, 2010 |

| ↑5, ↑7 | Poynor. Out of the Studio: Graphic Design History and Visual Studies, 2011 |

| ↑6 | Triggs. Graphic Design History: Past, Present, and Future, 2011 |

| ↑8 | نص ملتقي شرم الشيخ |

| ↑9 | Khan. Revolution For Kids: Dar El Fata El Arabi, Recollected, 2010 |

| ↑10 | Gacek. Arabic Manuscripts, 2009 |