The objective of this essay is to bring forward the topic of heritage management, erasure and ruination in the Nile river delta as a result of sea level rise and societal collapse. It is an investigation into a possible community resilience through the deep adaptation agenda, a term coined by Professor Jem Bendell in his now well-known paper “Deep Adaptation”. Bendell is a professor of sustainability leadership and has written about monetary economics and the need for ‘Deep Adaptation’ in response to environmental crises. Parallel to that, the essay will highlight the importance of heritage, specifically the numerous ancient ‘tells’ (meaning small mounds) to a population historically dependent on it, yet presently disenfranchised from. One could speculate that there should be new ways to preserve heritage rather than just maintain it as a staple of memory.

The paper aims to highlight the factors affecting the delta’s long heritage and how sustainable archaeology and tourism can benefit the landscape and not align itself with the mainstream archaeology practiced in Upper Egypt, which will be mentioned later in the essay. How can we develop an acceptance of geological and climate change to the region, and channel that into alternative methods of prosperity in the forgotten archaeological realm of the nile Delta?

Another question is raised around how the tell can benefit from local archaeology by becoming more accessible to non specialists in order to raise awareness of a deteriorating landscape as well as amplify its outreach.

of the Nile Delta

Introduction

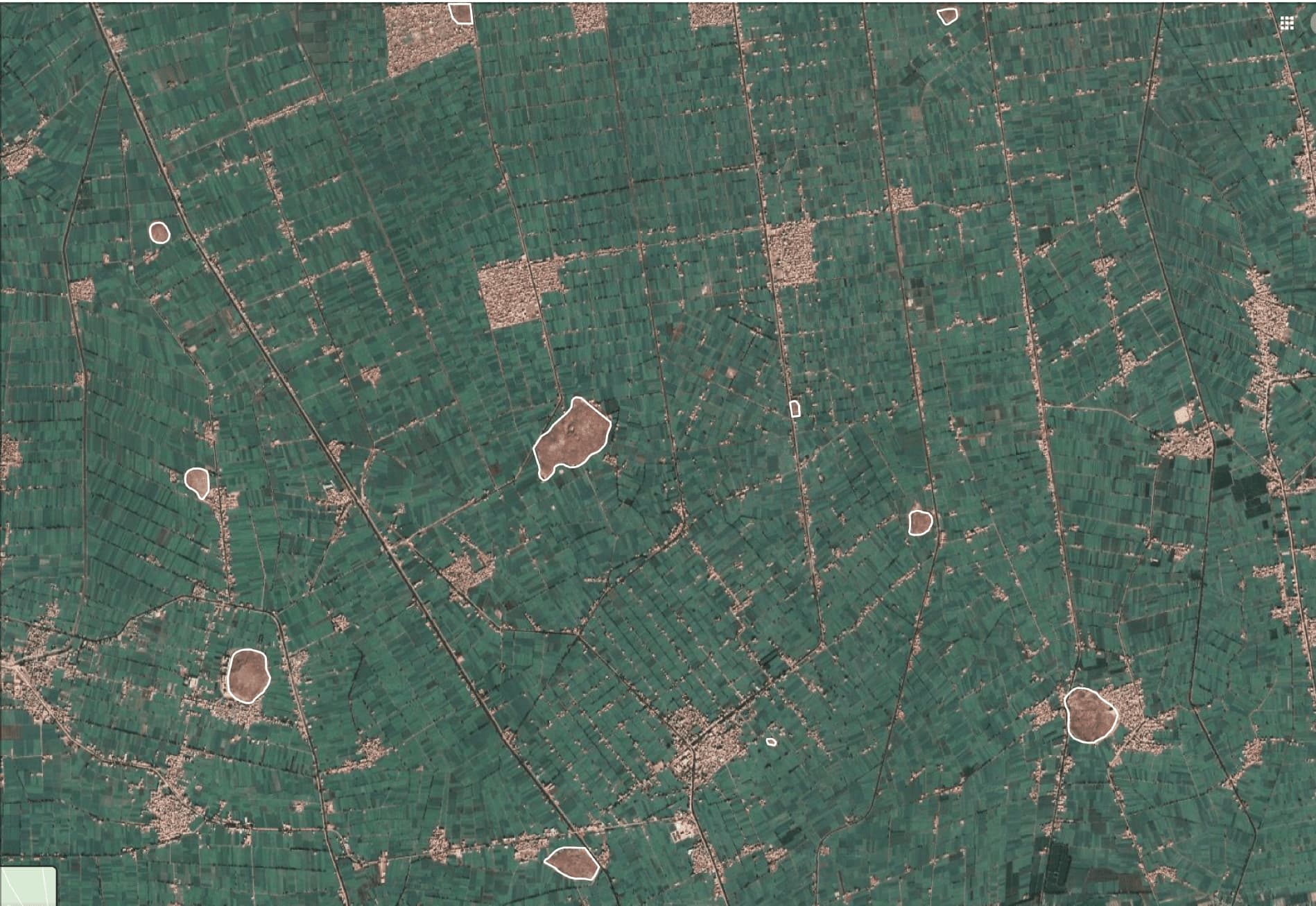

Formed by branches of the Nile in the prehistoric period, the Delta floodplain has seen continuous human occupation and is now is one of the most populated regions in Egypt. Responding to fluctuations in the flood discharge of the Nile, incursion and retreat of the Mediterranean shoreline, as well as subsidence of the land, the floodplain of the Delta is a showcase of how climate change and geological processes can shape landscapes. It was in the context of this moveable, changeable and dynamic landscape that Egyptian civilisation was forged, fuelled by countless external groups from the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, Greece, Rome, and Europe, interacting with Egyptians through trade, invasions or population movements. Levantine trading posts, Greek industrial cities, monasteries, mosques, royal tombs, forts, shipyards, orchards, cemeteries, capital cities and much more are witness to a procession of world events. Yet this precious world heritage is now threatened by coastal erosion, fishponds, expanding settlements, and runaway development. Originally inhabited by no more than a million people, the Delta is now home to as many as 43 million, a figure expected to double in the next thirty years. Thousands of villages, hamlets, towns and farmsteads are spreading so fast that they are threatening sites of all periods, from Rosetta with its famous medieval architecture to barely known archaeological sites that were once the majestic capitals of ancient Egypt, such as Sais and Buto. The physical expansion of the Delta dwellers is accompanied by an array of activities that threaten the very existence of ancient sites, from building to the removal of soil, sand and gravel for construction, drowning sites with sewage and effluent water, and turning sites into fish farms. Moreover, the temptation of illicit digging is often irresistible. Climatic changes in the form of sea level rise and fluctuating Nile flood regimes also pose a threat to this vulnerable area.

Archaeologically, the Delta contains various sites with long excavation histories, including Alexandria, Bubastis, Buto, Merimde Beni Salame, Naukratis and Tanis, amongst many others. Despite this wealth, however, the Delta is comparatively unexploited by tourists, as these sites lack the accessibility and high profile enjoyed by Upper Egyptian sites such as the Valley of the Kings, Kom Ombo, Dendera and Abu Simbel. While a challenge, however, the Delta holds rich rewards, not just archaeologically but culturally, socially and environmentally and in the realm of archaeology considered to be as relevant to its counterparts in Upper Egypt.

Apart from those few sites named above, the Delta has traditionally been overlooked by archaeological investigation, and has hindered archaeology due to local land disputes and its geographical remoteness, and while the balance of archaeological excavation and survey has started to be redressed in recent years, it is now more vital than ever that work be increased in this threatened area. Coastal erosion, expanding settlements and runaway development by a population exceeding 40 million (a figure expected to double in the next thirty years) are threatening sites of all periods and types. Thousands of villages, hamlets, towns and farmsteads are spreading in an unprecedented tide of human swell, threatening sites of all periods from Rosetta with its famous medieval architecture to the barely known archaeological sites that were once the majestic capitals of ancient Egypt like Sais and Buto. The physical expansion of Delta dwellers comes with an array of activities threatening the very existence of ancient sites – urban sprawl and land reclamation building over sites, increased agriculture, removing soil, sand and gravel for construction, drowning sites with sewage, and looting.

Top right: Overbuilding by development projects

Bottom left: Subsidence

Bottom right: Overbuilding Subsidence by towns and cemeteries

Environmental Threats

The Delta holds two-thirds of the country’s rapidly growing population, and produces more than 60% of its food supply. It is the breadbasket of the nation. Pressure is starting to tell, both economically and environmentally. The increasing urbanisation of the Nile Delta is having an adverse effect on the environment. With more people living in the Delta it means more cars, more pollution and less land to feed them all on, just at a time when increased crop production is needed most. Yet the desertification of land through human habitation is only the beginning of the problem. The freshwater of the Nile – which has enabled Egypt to survive as a unified state longer than any other territory on earth – is creaking under the strain of this population boom. Salinity is creeping into the Delta, with one of the worst-affected regions being Kafr El Sheikh. Coastal farmland has always been threatened by saltwater, but salinity was traditionally kept at bay by plentiful supplies of freshwater flushing out the salt, which no longer occurs due to the Aswan High Dam. As the Delta substratum becomes more porous seawater has begun to infiltrate the Nile Delta aquifer, a vast source of underground water, which is under increasing pressure from the burgeoning population. Upstream demand has increased, reducing the amount of Nile water reaching the Delta, and increasing the prevalence of sewage, toxins and other impurities in water that does so. Farmers have battled falling fertility via the use of chemical fertiliser, or have turned their plots into fish farms.

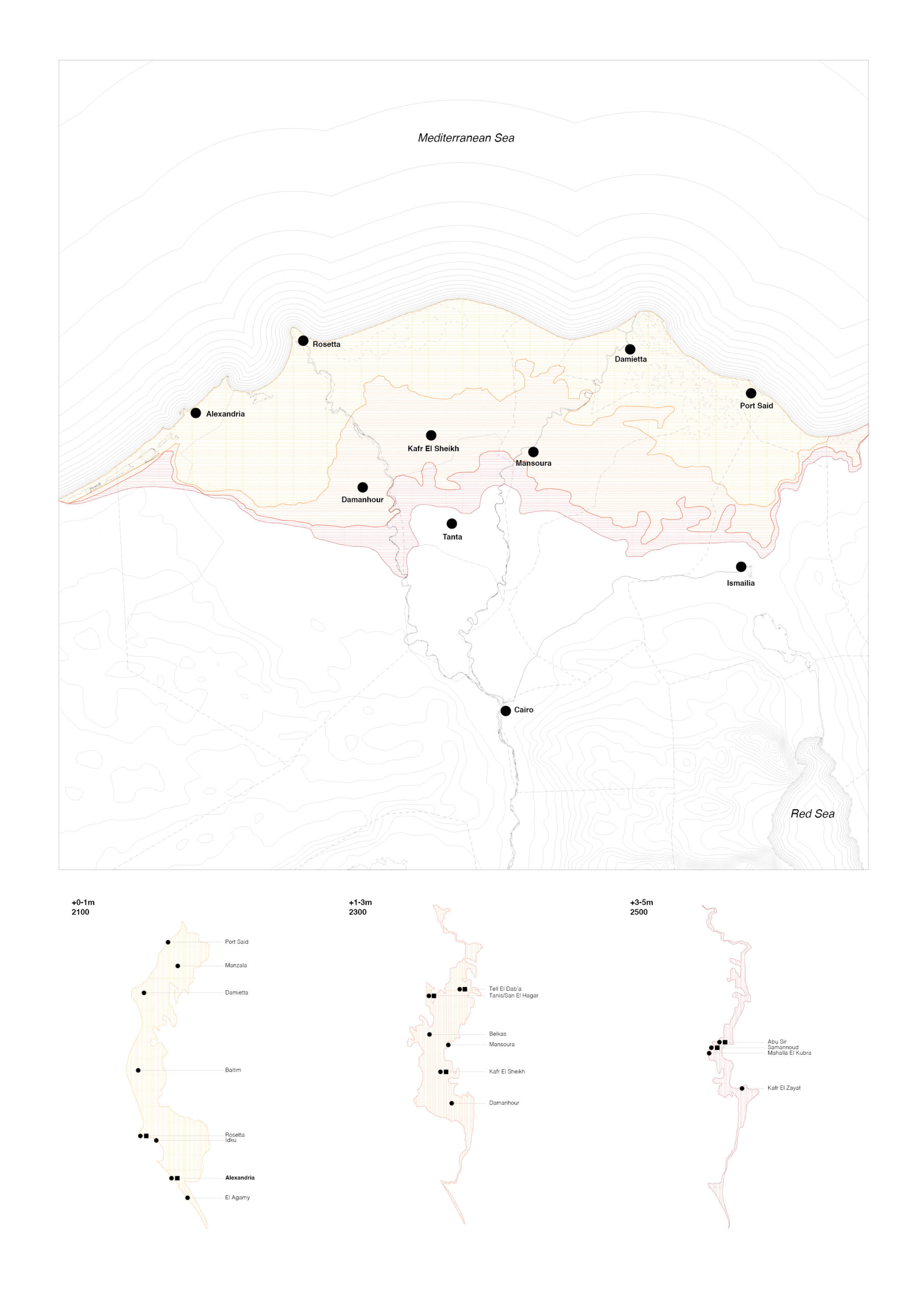

Climate change may however be the biggest threat. While controversial at every level, most parties have been forced to agree that the ice caps are melting owing to increases in average land and sea temperatures. The climate and environment of the Nile Delta has been constantly changing throughout the Holocene and before; with an intensification of anthropogenic impacts from the Pharaonic period onwards. ‘The Nile Delta has a particularly long history of vulnerability to extreme events (e.g. floods and storms) and sea-level rise, although the present sediment-starved system does not have a direct Holocene analogue’. In the twenty first century climate change is set to alter the Nile Delta yet further. The Arab Climate Resilience Initiative (part of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) state that these continuing increases in temperature and sea level will negatively affect biodiversity, food security, water availability, agriculture and tourism, while the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) declared the Nile Delta to be in the top three of the world’s regions most threatened by rising sea level: ‘even the most optimistic predictions of global temperature increase will still displace millions of Egyptians from one of the most densely populated regions on earth’. The IPCC (2013) predicts a rise of 0.28 to 0.98 metres by 2100; this would destroy at least 12.5% of Egypt’s cultivated areas, and displace about eight million people. The higher estimate would see a much more serious result, perhaps in line with McGrath’s estimate of 20-30.% of the Delta being submerged (2014). Given that much of the Delta coastline lies between zero and 1.0 m at above sea level, any rise in the sea level would see farmland and cities – including Alexandria – transformed into an ocean floor.

of agricultural and archaeological communities.

Deeper inland, the threat of climate change slightly thins whereas the threat of overpopulation, sewage, looting and agricultural levelling puts the ‘tell’ (could also be named ‘kom’) in a condition of rapid deterioration. The ‘tells’ unfortunately become vandalised by the very same population that occupies it and inhabits the landscape surrounding it. Perhaps climate change affects local farmers more than others at the moment with the increase of soil salinity and a slow decline of the delta’s fertility (hence the government’s agricultural expansion into the desert). This has led to an interesting phenomena of robbing the ‘tell’s’ soil and ancient mudbrick that lies beneath. This is because the mudbrick walls that once were settlements, villas, and remnants of an earlier dynasty, amazingly still contain minerals and moisture which deems it highly fertile. What is interesting is that of course, any found artefacts may be of value – but in dire conditions and the possibility of a societal decline in the region has labeled even soil as another advantage the ‘tell’ has.

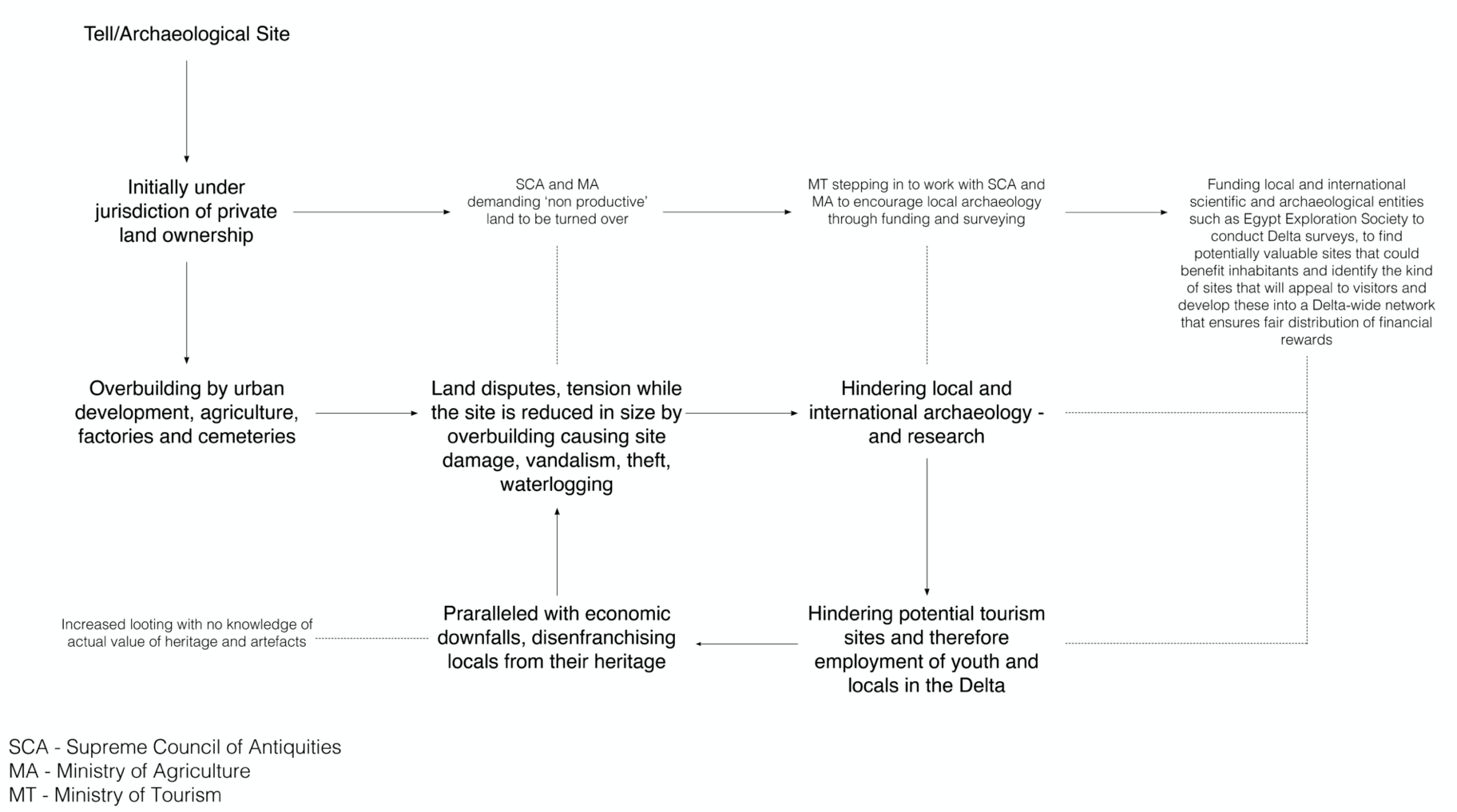

Furthermore, these small landscapes, ones that are surveyed but not yet excavated, usually fall under private land ownership. As a result, this has led to serious tensions. Local populations are frustrated at their inability to farm what appears to them to be unremarkable ‘archaeological’ land, while archaeologists are confounded in their efforts to understand these sites by land disputes and a lack of resources. Neither side can be utterly victorious yet the Delta’s heritage must be preserved. Locals must continue to prosper. And the ‘tell’ must escape its own erasure.

the ‘tells’. Diagram.

Deep Adaptation and Resilience as a Community

Today, you are left with a dormant mound, a sign of unfulfilled archaeological and social potential with a lost sense of belonging to the locality and vice versa. A population disenfranchised from its own landscape. The Delta has traditionally failed to benefit directly from the tells and its tourism. However, if a site has been fully excavated or not, and is not a touristic or archaeological draw, should it be kept from cultivation indefinitely?

We do not know for certain the disruptive extent and impact of climate threat and where it will be most felt, especially as economic and social systems will respond in different and complex ways. But the evidence is accumulating that the impacts will be catastrophic to our livelihoods and the societies that live within. Our norms of behaviour, may also degrade. And when we contemplate this possibility, it may seem abstract. In his paper, Jem Bendell argues that “we do not know what the future will be. The evidence before us suggests that we are set for disruptive and uncontrollable levels of climate change.” This highlights, as much of the paper does in fact, a strong and required sense of acceptance of what is to come. The paper is written in a way to make you feel uncomfortable and emergent, yet with a feeling of understanding rather than despair at such a colossal force like climate change, which Timothy Morton calls a “hyper-object”, an object or a concept so large and threaded in so many ways it cannot be tangible. This essay does not focus on such effects globally, but rather looks at one microscopic repercussion to a specific region and that is the nile delta, as well speculating on new methods of preservation. Indicating that an erasure of heritage and the concept of ruin to dust will in fact hinder many aspects of daily life for inhabitants of the delta. All the factors mentioned above ultimately hinder local and international archaeology, thus hindering youth and employment in the archaeology and tourism sector. So a system of denial would not help us, in fact it would create a sense of hopelessness among the general public. Indeed, we as the general public and the inhabitants of the delta must adopt resilience. Resilience as a means of developing or using such disturbances to spur and trigger innovative thinking. In the case of this essay, the question that resilience raises is one of longevity. How could the locals begin using the ‘tell’ to reinstate cultural tradition, create a sustainable archaeology, and create a positive social effect for the population?

Bendell further supports such an argument by saying that “resilience is the capacity of a system, be it an individual, a forest, a city or an economy, to deal with change and continue to develop. It is about how humans and nature can use shocks and disturbances… to spur renewal..” There are currently more than one hundred ‘tells’ and ‘koms’ scattered around the delta, from east to west. Utilising these mounds by implementing a sustainable architecture, a universal and cohesive language, could then initiate income and seriously benefit the region in different ways to traditional archaeology and tourism.

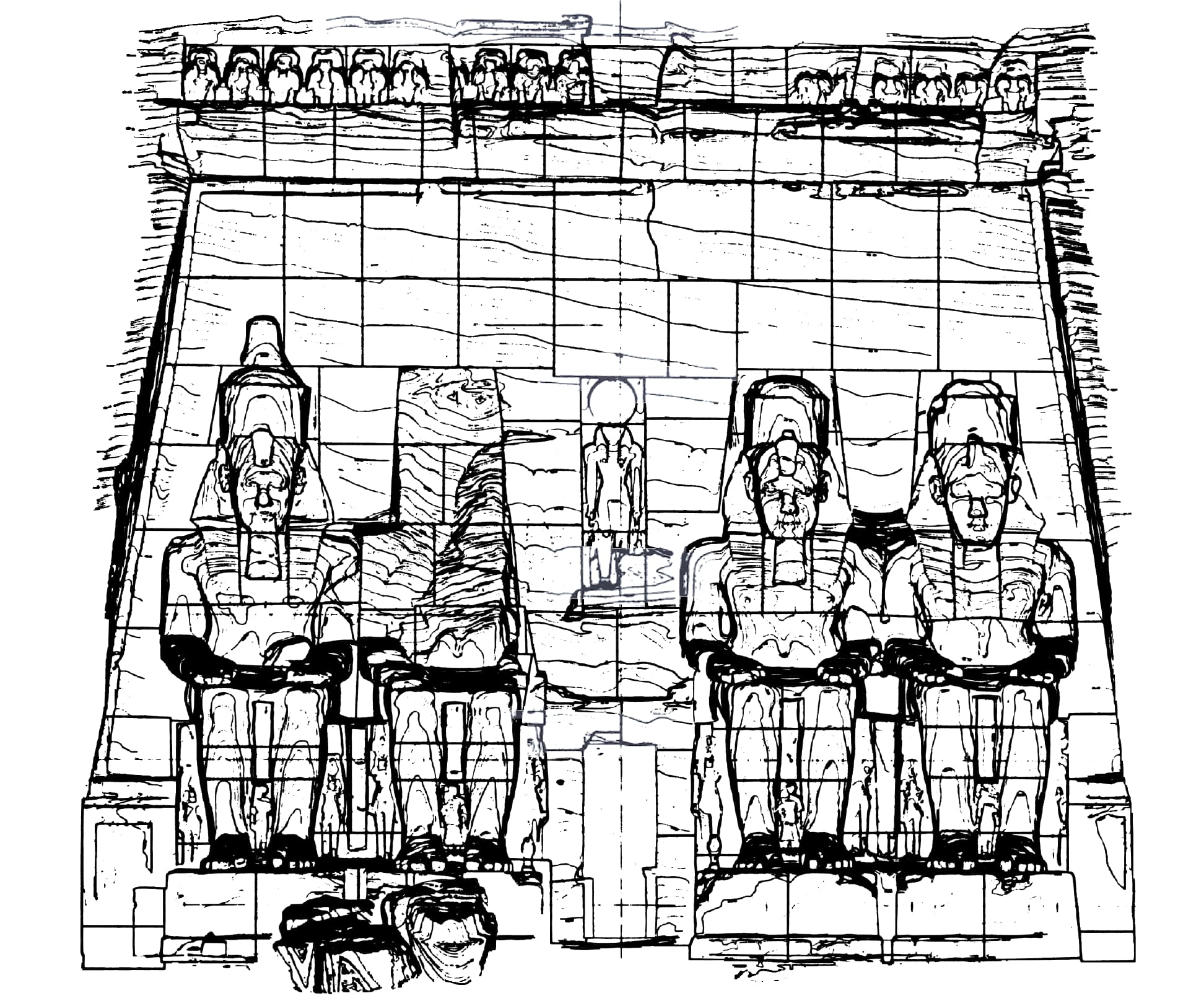

The Case of Upper Egypt and the Aswan High Dam

By thinking of new ways of preservation in Egypt, one that would bring communities together rather than displace them, as well as think of a decentralised and sustainable way to do so, one must understand and acknowledge previous examples of preservation in the land. One must also grasp the scale, resources and effort put into such projects when faced with catastrophe, be it natural or man made. Most notably, the rescue of twenty three monuments in Upper Egypt in the 1960s by the state and UNESCO. In 1959, an international donations campaign to save the monuments of Nubia began: the southernmost relics of this ancient human civilization were under threat from the rising waters of the Nile that were about to result from the construction of the Aswan High Dam. The most famous of the monumental project was the salvage of Abu Simbel. The salvage of the Abu Simbel temples began in 1964 by a multinational team of archeologists, engineers and skilled heavy equipment operators working together under the UNESCO banner; it cost some US$40 million at the time. Between 1964 and 1968, the entire site was carefully cut into large blocks (up to 30 tons, averaging 20 tons), dismantled, lifted and reassembled in a new location 65 metres higher and 200 metres back from the river, in one of the greatest challenges of archaeological engineering in history. Some structures were even saved from under the waters of Lake Nasser. Today, a few hundred tourists visit the temples daily. Such an example demonstrates the meaning of preservation in the face of flooding, in this case from Lake Nasser. It further demonstrates the positive effect preservation can have. The temple stands alone above the reservoir but has generated a huge income and cultural definition for the inhabitants and their future generations.

The delta is different. It is truly forgotten. One major aspect that puts the delta second to Luxor and Aswan is what is found there. People stand in awe in the midst of large temples all around Egypt, yet the ruins of the delta do not match that scale. Or at least not yet. With the exception of the ancient city of Tanis, many of the found objects could be quite small. It ranges from pottery shards to mudbrick walls, and rarely some precious fragments of limestone statues. Although it doesn’t seem like a lot, the ‘tells’ actually have an abundance of such objects and therefore provide detailed insights on the past, and help archaeologists and conservationists stitch up fragmented perceptions of these times.

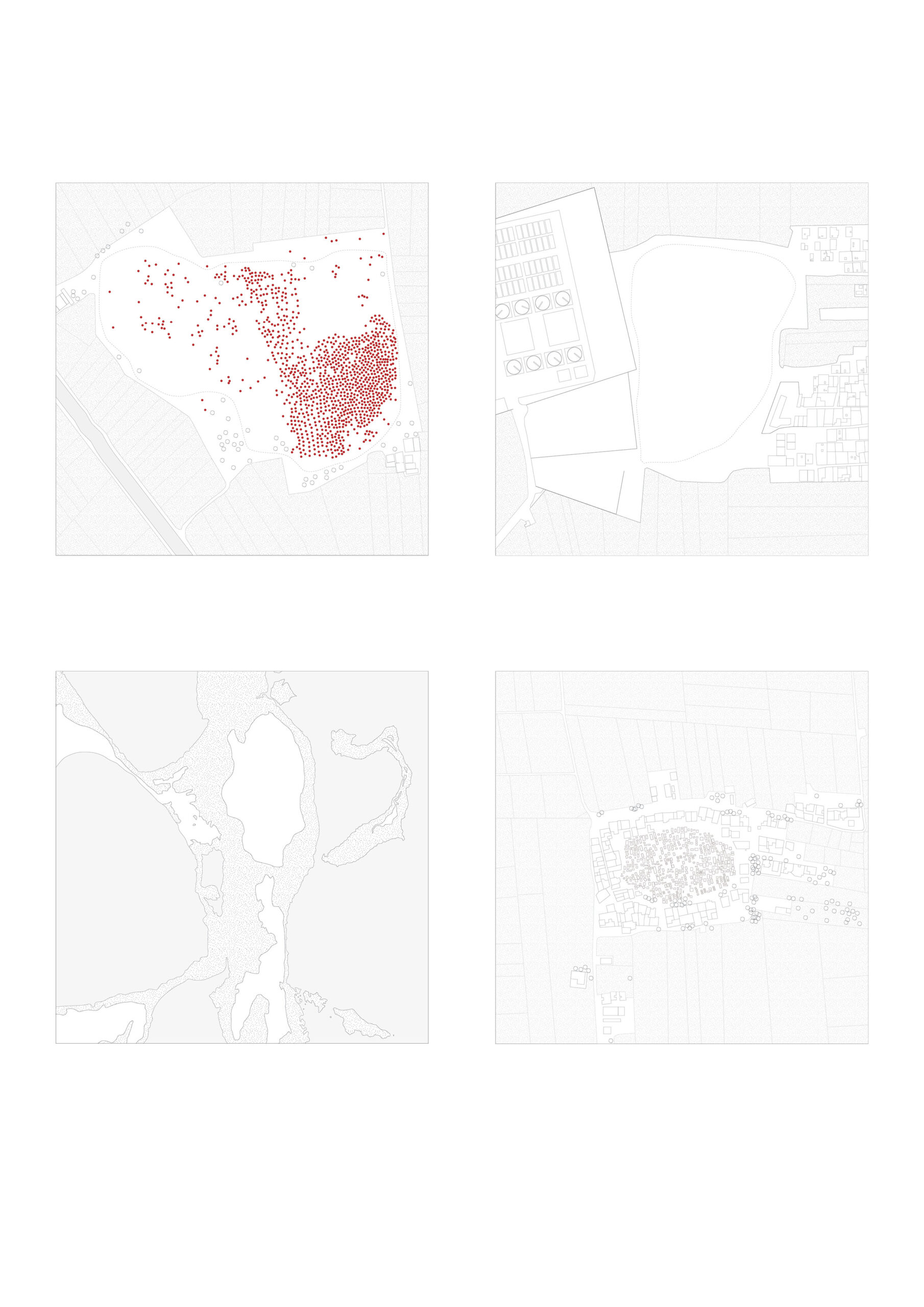

Tanis and Tell el Daba

Upon a site visit in 2019, the eeriness and disregard of the ‘tell’ resonated. Two sites were visited, and both very different from each other. The first was Tell El Dab’a, an ancient ‘tell’ sitting on top of what was a settlement and port city for the Hyksos; an Asiatic dynasty that rivalled Egypt. It became clear also that ‘tells’ are highly censored, yet mildly protected. Photography was only allowed with a permit, and if there are no excavations, there is nothing to see. If there are excavations, it is not publicly accessed and closed off.

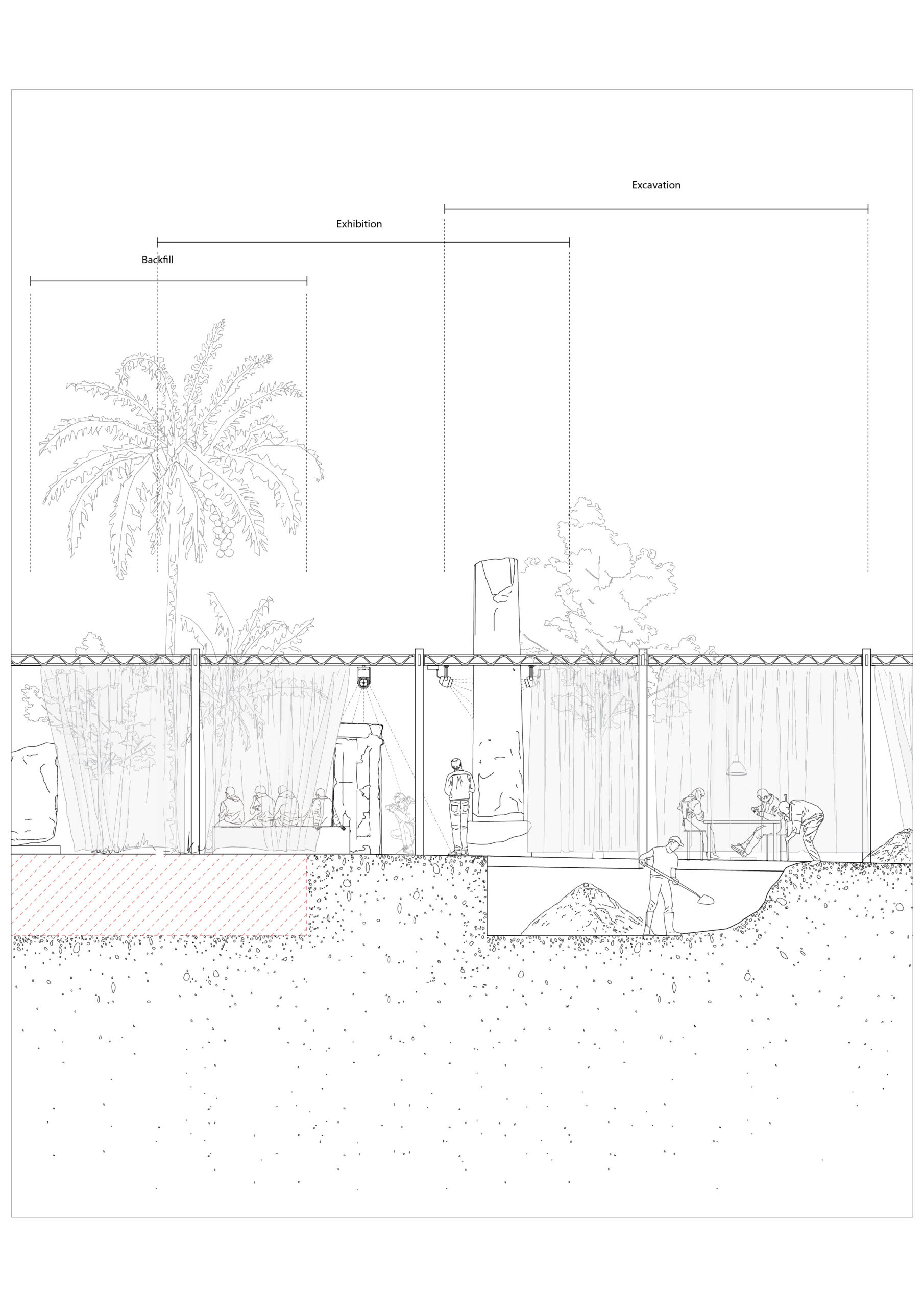

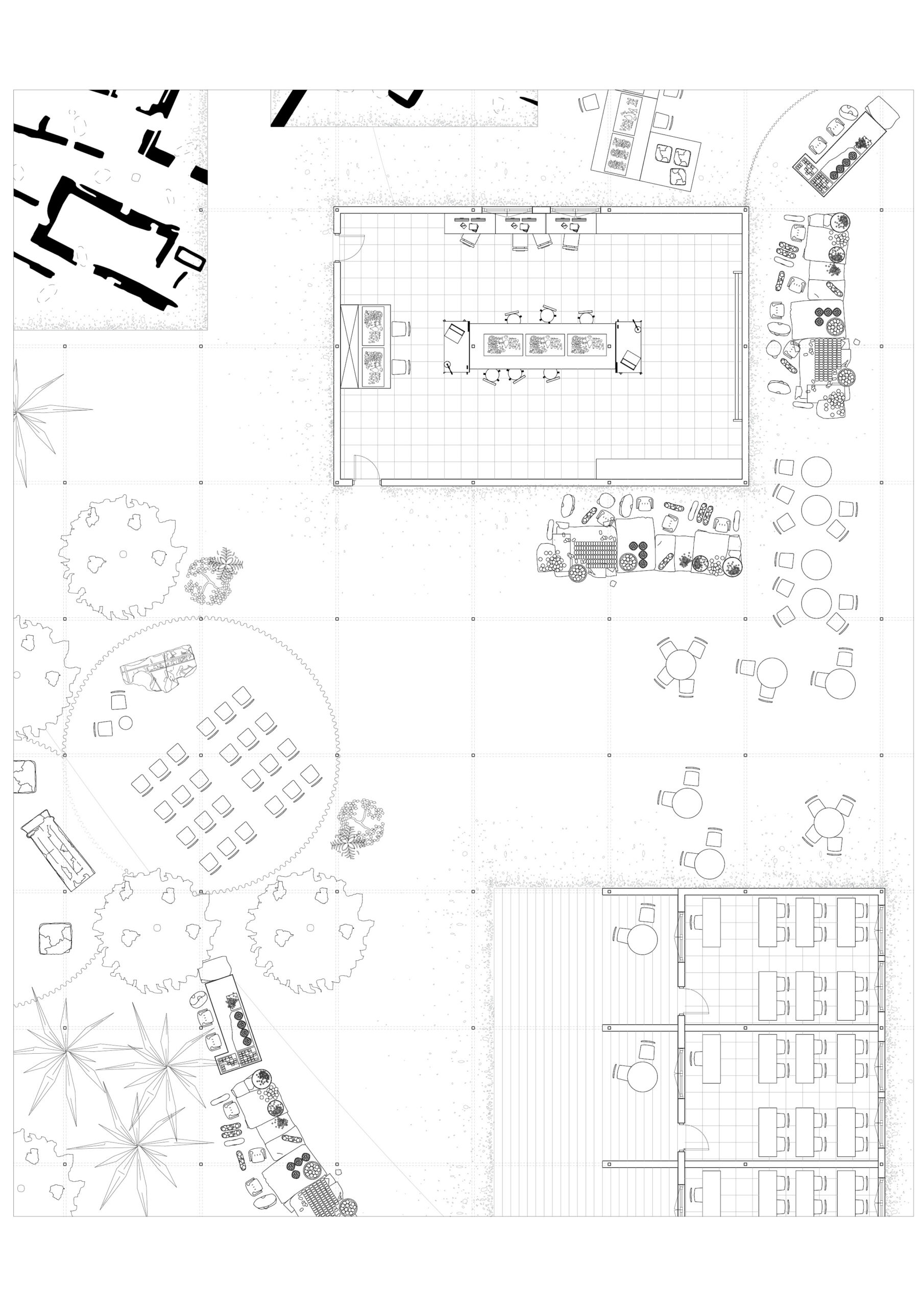

The second site, was Tanis; an open air museum sitting on the largest ‘tell’ in the delta. It is open to the public but is not fully utilised. However, it contains the largest scale of artefacts and perhaps is why it attracts the most local and international tourists in the delta. This site became evident upon observation of what limited benefit locals have made of the landscape. The delta cannot be considered as an open air museum, the large statues there being left to decay. We must rethink museology and curation of what is extracted from the mound. What if we can juxtapose current excavations, with educational and outreach programmes and also exhibit various artefacts? Such ideas should be discussed in order to reshape the components of daily life in the delta.

Nile Delta 2019

Conclusion

The Nile delta, and generally tourism has been damaged by recent events in Egypt, and while numbers are now beginning to increase again, there must be a visible change in the way that the past is perceived, handled and benefitted from. The Delta has traditionally failed to benefit directly from tourism, the revenues from which are diverted away, leaving local populations not only socially disenfranchised from their past, but indisposed to protect and embrace their own heritage. Opportunities often present themselves. It is obvious that not every site can be a tourist attraction; sustainable tourist management needs to be formulated within the state, to identify the kind of sites that will appeal to visitors and develop these into a Delta-wide network that ensures fair distribution of financial rewards. Positive adaptation consists in fashioning a work to resemble traditional models. Negative adaptation opposes it, and consists in fashioning a work not to resemble them, in setting it in contrast with them. In both cases, the work stands in a determinate relationship to tradition, whether positive or negative.

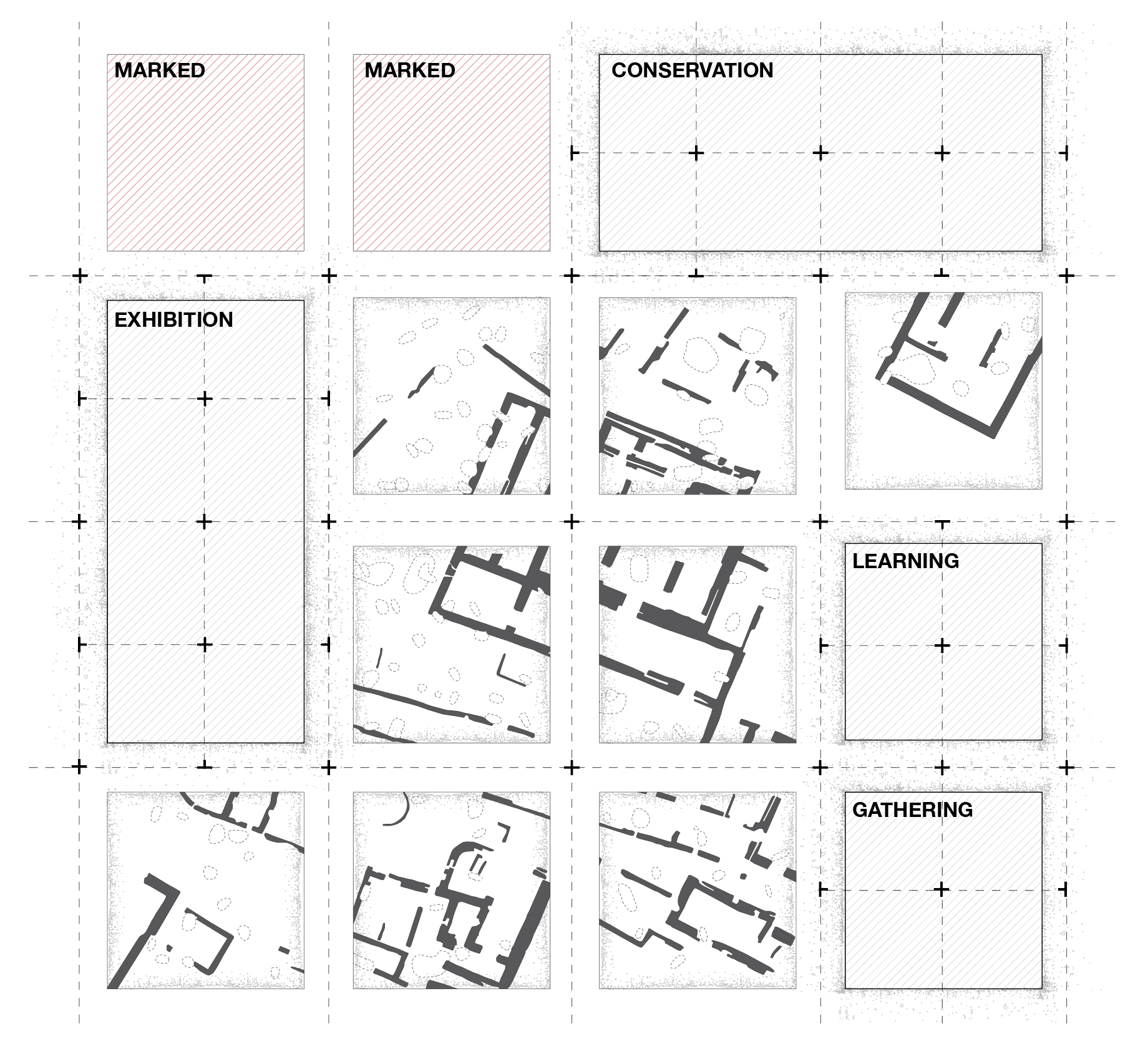

A new material system should be proposed, one that provides an architecture in which the process of excavation and conservation becomes the sight, parallel to exhibiting and publishing the findings. So in conclusion, the condition of deep adaptation in this essay expresses how residents of the rural nile delta should begin to innovate and mobilise the tell, a small patch of land that is highly contested and will deteriorate with sea level rise. Resilience will restore a sense of dependence on the heritage and and will have a positive social effect. Such would be an indirect response to the climatic changes in the region as a means of maintaining the landscape for everyone. If a project is deployed in all possible sites, it can begin to establish a common language of local thriving, be it archaeological or even agricultural, a place where farmers could trade and sell goods to visitors and those who would be transforming the ‘tell’

architectural universal language on the ground. Drawing and collage – 2020